Cleveland is village on the Midlands Highway about 50 kilometres south of Launceston. Cleveland was developed in the 1840s as a stopping point on the coaching route between Hobart and Launceston. Historic buildings that have survived include St Andrews Inn (1845), Cleveland House (originally the Bald Faced Stag Inn built in 1838) and a Union Chapel built in 1852.

Construction of Cleveland’s Union Chapel got under way in 1852. In August the Colonial Times reported:

“…We observe an advertisement calling for subscriptions towards the erection of a new place of worship in the township of Cleveland. Hitherto this spot has been totally destitute of the means of Christian instruction. Several enterprising individuals concerned to promote such means have liberally commenced a subscription which has nearly reached £60. On application Mr. Thornell generously consented to give a quarter of an acre of land for the building, which, when completed, will be open to the services of Ministers of all Evangelical denominations. The claim of this township commends itself to the liberality of every Christian. We hope that an adequate sum will soon be raised to remove the present destitution which there exists.…”.

Construction of the chapel was completed in early 1852 and the building was officially opened on Sunday 15 February. Reverend Miller, a Congregational minister from Hobart preached the first sermon. In the following month regular Presbyterian services were conducted by Reverend Russell of Evandale. The chapel was also used by Anglicans and probably also by Wesleyan Methodists.

The Cleveland Cemetery:

The chapel’s cemetery contains many interesting headstones. One stone reveals a shocking story and is a reminder of criminal violence common in the 19th century. This is the gravestone of William Wilson who was murdered in 1883 by two youths, James Ogden and James Southerland. The murder investigation and subsequent trial received sensational treatment in the national press replete with lurid details. Popular interest arose partly due to the age of the murderers (18 and 20) but also because of their lack of remorse and the brutality of the killings.

The death of William Wilson was the final act that ended a week of criminal acts by the two youths in which two murders were committed. James Ogden and James Sutherland had called at the Launceston watch house on 7th April to report that a girl named Bourke had robbed Ogden of 12 shillings in a brothel. The following day they called at the Woolpack Inn, 11 kilometres from Launceston saying they were going to Campbell Town to look for dogs and a trap they had lost. They were next seen near a hut a Symond’s Plains, which had been robbed of a gun.

Their first victim was a forty-year old man, Alfred Holman. His murder was reported vividly in the Gippsland Times:

“One of the ruffians is surmised to have fired at Holman as he was driving the cart along the main road. The shot is supposed not to have killed him, for from the appearance of the ground in the vicinity where the deed was perpetrated it is evident that a determined struggle took place. Holman after receiving the shot, probably fell from the cart, but rose to his foot and faced his antagonists. Being partially stunned he was at a disadvantage, and his two cowardly assailants must have beaten him about the head with the stock of a gun or pistol, and then dragged the body along the road…. they endeavoured to conceal the marks of blood by scattering white sand over it, but without avail, for the blood oozed through in many places".

The second victim was William Wilson who lived with his wife and 4 children near Cleveland. This was reported in The Tasmanian as follows:

“He [Wilson] was awakened by stones being thrown on his roof. He went outside, found nothing, so went back to bed. When another stone hit the roof he again went out. His wife heard a strange voice then a shot, so she too jumped out of bed and ran outside. Her husband staggered past her saying that he had been shot. He collapsed outside and she ran inside and locked the door. More stones hit the roof, then a voice outside said to set fire to the hut. Soon smoke and flames came into the hut and another shot was fired, forcing the family outside. Mrs Wilson saw a man she later identified as Southerland, with a gun in his hands. She also recognised Ogden. The two men dragged off one of Wilson’s girls but she later ran away”.

Mrs Wilson also received gunshot wounds but survived. Following a manhunt, Southerland and Ogden were arrested and taken to Campbell Town where they claimed that it was all only meant as a joke.

Justice was swift in 19th century Tasmania and the trial of Southerland and Ogden had been concluded and justice meted out by June 1883, barely two months after the murders. The Launceston Examiner reported on the fate of the two men:

“The prisoners James Sutherland and James Ogden, convicted of the murder of William Wilson and Alfred Holman at Epping Forest in April last, were executed this morning in the Campbell Street Gaol…. Neither of the prisoners had slept during the night, saying that they would see as much as they could of the world that was so soon to be left, and both softened in their demeanour during the night. This morning Sutherland requested that Mr Mace [the chaplain] to send to Mrs Wilson and Mrs Holman and ask them to forgive him, and he spoke bitterly of the treatment he received during his lifetime, saying the world had not been a pleasant one to him, that he had no parents to look after him…”

The execution can only be described as wretched. The Examiner reported on the final scene with some pathos:

“At 8.05 a.m. they left their cells, after having been pinioned by Solomon Blay, the hangman; and preceded by the Rev. Mr Shoobridge, reading a portion of the Church of England burial service, both men walked calmly along the bridge leading to the scaffold, Sutherland's step being as firm as ordinarily, while Ogden, who carried in his right hand a bunch of flowers sent to him through the Rev. Mr Shoobridge by a little girl attending Trinity Church Sunday-school, trembled violently, but otherwise made no sign. When the hangman placed the noose round Sutherland's neck he pulled himself together, never flinching, Ogden also keeping firm, and the muscles of neither of their faces moved as the fatal cap was drawn over their heads. The bolt was drawn at 8.10 a.m., and side-by-side the unfortunate lads were launched into eternity. Standing on the scaffold they looked more boyish than ever, making it difficult to believe them the perpetrators of the deeds for which they justly suffered death. Mrs Ogden states that it was reading the history of the Kelly gang caused the boys to commit these crimes. After hanging an hour the bodies were out down, the little bouquet sent to Ogden being found tightly clenched in his hand, and Dr Graham certified that both were dead. Casts of their heads were then taken…and at 12.30 p.m. the bodies were placed in a hearse by [and] conveyed to the Cornelian Bay Cemetery, where they were interred by the gaol officials without any religious ceremony. The execution of these two prisoners contributed to a count of over a hundred persons executed by Solomon Blay” *

* Solomon Blay (20 January 1816 – 20 August 1897) was an English convict transported to the Australian penal colony of Van Diemen's Land (present-day Tasmania). Once his sentence was served, he gained notoriety as a hangman in Hobart, and is believed to have hanged over 200 people in the course of a long career spanning from 1840 to 1891. This made him the longest serving hangman in the British Empire.

|

| Photograph: Duncan Grant 2018 |

|

| Photograph: Duncan Grant 2018 |

|

| Photograph: Duncan Grant 2018 |

|

| Photograph: Duncan Grant 2018 |

|

| Photograph: Duncan Grant 2018 |

|

| Photograph: Duncan Grant 2018 |

|

The sign erroneously dates the chapel to 1855 instead of 1852. Photograph: Duncan Grant 2018

|

|

| William Wilson's headstone - Photograph: Duncan Grant 2018 |

|

| The murderers James Ogden and James Sutherland - source: National Library of Australia Portrait of James Sutherland and James Ogden, Tasmania, ca. 1878 [picture] 1878 http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-138063792 |

|

| Photo: Libraries Tasmania - LPIC 33/1/21 |

|

| The interior of the chapel |

|

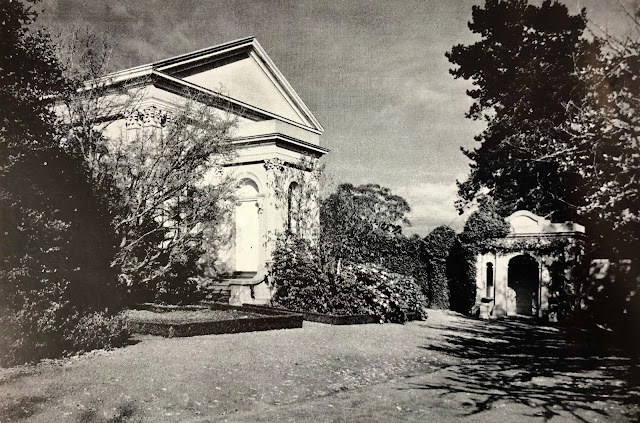

| An early photograph of the chapel - Photographer: Frank Heyward - Early Tasmanian Architecture, Libraries Tasmania [album 1] [picture] [914783] |

|

| List of subscribers to the Cleveland Chapel - Launceston Examiner, Saturday 26 July 1851 |

|

| Notice of the Chapel's official opening. Launceston Examiner 15 February 1852 |

Photographs of headstones of interest in the Cleveland cemetery:

|

| Photograph: Duncan Grant 2018 |

|

| Photograph: Duncan Grant 2018 |

|

| Photograph: Duncan Grant 2018 |

|

| Photograph: Duncan Grant 2018 |

|

| Photograph: Duncan Grant 2018 |

A link to all the gravestones at the Cleveland Chapel cemetery can be found at this link: HERE

Sources:

Launceston Examiner, Saturday 26 July 1851, page 2 Colonial Times, Friday 1 August 1851, page 3

Launceston Examiner, Wednesday 11 February 1852, page 6

Launceston Examiner, Saturday 14 February 1852, page 3

Launceston Examiner, Saturday 6 March 1852, page 2

Tasmanian, Saturday 21 April 1883, page 10.

Tasmanian, Saturday 14 April, 1883.

Tasmanian Saturday 28 April, 1883.

Examiner, Tuesday 5 June 1883, page 3.

Gippsland Times, Wednesday 18 April 1883, page 1.

The Mercury, Friday 8 January 1837, page 5

http://www.penitentiarychapel.com/html/executions.htm

http://www.abc.net.au/local/stories/2015/09/15/4312635.htm

Enlightening reading. Thankyou for the research.

ReplyDelete