No. 139 - Aberdeen Methodist Church - "Grunting Like A Pig"

The foundation stone for the Aberdeen Methodist Church was laid on the 2nd July 1914, 4 days after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo. There was no sense of foreboding at this ceremony or at the opening service two months later:

“The opening services of the new Methodist Church at Aberdeen on Sunday was a great success. There were overflowing congregations at both afternoon and evening services…. On Wednesday a tea meeting was held in the afternoon and a concert and coffee super at night….the concert closed with the singing of the National Anthem”.

Most rural churches tend to have very quiet lives that go unreported aside from the regular fairs, harvest festivals and anniversary services. But, if one digs deeply enough, a unique story is usually found. The church at Aberdeen is no acceptation. While these stories may not be strictly 'church history' they are part of the rich tapestry of social history. This is valuable in bringing the buildings and people who worshiped in them alive and into sharper focus as 'real' people with whom we can identify.

Aberdeen’s 'unique' story is about a disturbance in church that resulted in two separate trials. The ‘offence’ committed would hardly be considered a crime today. On an autumn night in 1924, a group of youths caused a disturbance at a harvest festival service led by lay preacher Joseph Langdon. Langdon, who was a bricklayer by trade, failed to persuade the youths to cooperate. The ongoing disturbance resulted in the police being called although the culprits had left the service by the time a policeman had arrived from Spreyton. The court cases were reported in several newspapers and these provide an insight into community standards and expectations as well as the problem of 'larrikinism' experienced by religious communities. The record of the first court case in comes from The Advocate:

“At the Devonport police court yesterday morning, before Mr F. N. Stops, …a man named Samuel Meers, and two youths named Allan Bramich and John Sherlock, were charged with disturbing the peace by making a noise while divine service was being conducted in the Methodist Church at Aberdeen on Sunday [9 March]. Meers pleaded guilty; the other two denied the offence.

Henry Hyland Denny, a warden of the Aberdeen Methodist Church, said that about 80 people were present at divine service on the evening the offence was committed. He heard Meers say: "Move up, make room, give us a seat," in a loud voice. [The] witness was up in the front of the building, and the three defendants were in the back. He also heard a grunting noise, as if made by someone imitating a pig. The disturbance continued at intervals for about half an hour. Then the defendants went out.

John Reid Foster, a steward of the church, said the defendants were laughing and talking, and he had to speak to them about it. Meers was grunting like a pig and "amusing" the others.

Both Sherlock and Bramich were found guilty. Superintendent Gunner asked that in view of the gravity of the offence, and also of the fact that on occasions it had been necessary to call a police constable out to Aberdeen while service was being held, [the] defendants should receive the full punishment of the law.

The P.M. [Police Magistrate] said the matter was a very serious one. It was a free country, and one of the reasons why it was so was that each person had free exercise in the matter of religion. Had it not been for the fact that there were no previous convictions, His Honour would have been inclined to send them to gaol without the option of a fine. He hoped they would never do the like again. Sherlock and Bramich were each lined £3, with 10/- costs. Meers was fined £3, with 8/- costs. A fortnight was allowed to each to pay the money”.

A second trial was held a week later for a fourth accused, Charles Howard, who was a fireman at the Melrose. In this case, Howard’s involvement could not be proved and the case was dismissed.

Both trials raise some interesting questions such as why were the young men attending the church service? The men did not seem to be regulars at the church or to be familiar to the churchwarden who intervened. From my reading of newspapers around the turn of the century, it would seem that there was a larrikin element in most communities, who saw the religious as easy targets. Groups such as the Methodists and Salvation Army appear to be frequently targeted by ‘larrikins’. On the other hand, the broader community and the authorities had little tolerance for this behaviour and consequences could sometimes be quite severe by the standards of today. While I don’t think that there are any ‘lessons’ of history to be learnt from this incident, it does give us an insight into human behaviour which is a 'constant' factor in history.

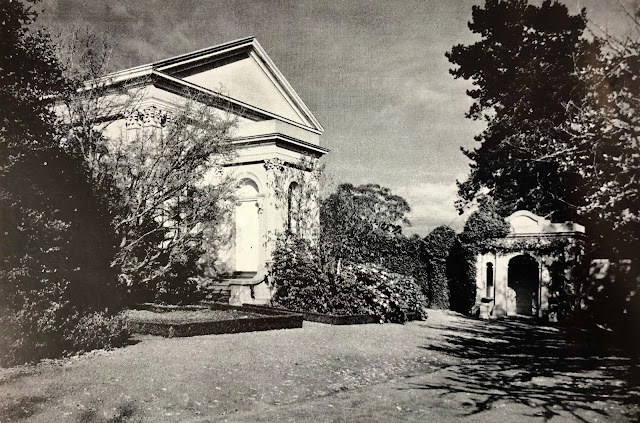

The church at Aberdeen is now a house curiously called 'Aberdeen Abbey'. Its tranquil country setting on the fringes of Devonport offer no hint of the 'dramatic' events at a harvest festival one autumn night almost 100 years ago.

“The opening services of the new Methodist Church at Aberdeen on Sunday was a great success. There were overflowing congregations at both afternoon and evening services…. On Wednesday a tea meeting was held in the afternoon and a concert and coffee super at night….the concert closed with the singing of the National Anthem”.

Most rural churches tend to have very quiet lives that go unreported aside from the regular fairs, harvest festivals and anniversary services. But, if one digs deeply enough, a unique story is usually found. The church at Aberdeen is no acceptation. While these stories may not be strictly 'church history' they are part of the rich tapestry of social history. This is valuable in bringing the buildings and people who worshiped in them alive and into sharper focus as 'real' people with whom we can identify.

Aberdeen’s 'unique' story is about a disturbance in church that resulted in two separate trials. The ‘offence’ committed would hardly be considered a crime today. On an autumn night in 1924, a group of youths caused a disturbance at a harvest festival service led by lay preacher Joseph Langdon. Langdon, who was a bricklayer by trade, failed to persuade the youths to cooperate. The ongoing disturbance resulted in the police being called although the culprits had left the service by the time a policeman had arrived from Spreyton. The court cases were reported in several newspapers and these provide an insight into community standards and expectations as well as the problem of 'larrikinism' experienced by religious communities. The record of the first court case in comes from The Advocate:

“At the Devonport police court yesterday morning, before Mr F. N. Stops, …a man named Samuel Meers, and two youths named Allan Bramich and John Sherlock, were charged with disturbing the peace by making a noise while divine service was being conducted in the Methodist Church at Aberdeen on Sunday [9 March]. Meers pleaded guilty; the other two denied the offence.

Henry Hyland Denny, a warden of the Aberdeen Methodist Church, said that about 80 people were present at divine service on the evening the offence was committed. He heard Meers say: "Move up, make room, give us a seat," in a loud voice. [The] witness was up in the front of the building, and the three defendants were in the back. He also heard a grunting noise, as if made by someone imitating a pig. The disturbance continued at intervals for about half an hour. Then the defendants went out.

John Reid Foster, a steward of the church, said the defendants were laughing and talking, and he had to speak to them about it. Meers was grunting like a pig and "amusing" the others.

Both Sherlock and Bramich were found guilty. Superintendent Gunner asked that in view of the gravity of the offence, and also of the fact that on occasions it had been necessary to call a police constable out to Aberdeen while service was being held, [the] defendants should receive the full punishment of the law.

The P.M. [Police Magistrate] said the matter was a very serious one. It was a free country, and one of the reasons why it was so was that each person had free exercise in the matter of religion. Had it not been for the fact that there were no previous convictions, His Honour would have been inclined to send them to gaol without the option of a fine. He hoped they would never do the like again. Sherlock and Bramich were each lined £3, with 10/- costs. Meers was fined £3, with 8/- costs. A fortnight was allowed to each to pay the money”.

A second trial was held a week later for a fourth accused, Charles Howard, who was a fireman at the Melrose. In this case, Howard’s involvement could not be proved and the case was dismissed.

Both trials raise some interesting questions such as why were the young men attending the church service? The men did not seem to be regulars at the church or to be familiar to the churchwarden who intervened. From my reading of newspapers around the turn of the century, it would seem that there was a larrikin element in most communities, who saw the religious as easy targets. Groups such as the Methodists and Salvation Army appear to be frequently targeted by ‘larrikins’. On the other hand, the broader community and the authorities had little tolerance for this behaviour and consequences could sometimes be quite severe by the standards of today. While I don’t think that there are any ‘lessons’ of history to be learnt from this incident, it does give us an insight into human behaviour which is a 'constant' factor in history.

The church at Aberdeen is now a house curiously called 'Aberdeen Abbey'. Its tranquil country setting on the fringes of Devonport offer no hint of the 'dramatic' events at a harvest festival one autumn night almost 100 years ago.

|

| Photograph: Duncan Grant 2018 |

|

| Photograph: Duncan Grant 2018 |

Sources:

Examiner Tuesday 1 April 1924, page 4

Advocate Tuesday 1 April 1924, page 2

Advocate Wednesday 9 April 1924, page 7

Examiner Saturday 12 September 1914, page 5

North West Post Friday 11 September 1914, page 3

Daily Post Saturday 4 July 1914, page 10

Comments

Post a Comment