No. 156 - The Salvation Army Citadel - Galvin Street - 'Breaking Windows'

When the new Salvation Army Citadel in Galvin Street was opened in 1942, the ‘Army’ had become a respected part of the religious landscape of Launceston. This had not always been the case.

"The Salvation Army had a seminal link with Tasmania. Launceston businessman and philanthropist Henry Reed, living in London, gave William Booth over £5000 to establish the Salvation Army on a firm footing in about 1870. In 1883 the Salvation Army Launceston Corps began operating, and corps were formed in Hobart, Latrobe, Waratah and other towns. Marches by these 'militant servants of Christ' through the two main cities with loud music attracted the larrikin element or 'roughs', who exploded flour bombs in the Salvationists' faces or threw mud and beer. Some Salvationists were arrested for marching without permission or refusing to desist from making excessive noise”.(1)

A survey of the press in Launceston during this time reveals that the ‘Army’ experienced significant opposition and harassment in the town up until the time its founder, General Booth, visited Launceston in 1891. In 1883, the year that the ‘Army’ was established in Launceston, a correspondent to the Daily Telegraph wrote:

“I see, …in your valuable paper this morning, that the larrikin element is spoken of as causing a disturbance in the Wesleyan Schoolroom last night, at a meeting of the Salvation Army. But sir, it was not those that are looked upon by the public as the larrikin class, but a few young men respectably dressed and holding places of trust in town. They were some of these who caused the most disturbance by shouting and trying to sing. Their conduct is disgraceful. Their names are well known….”

Amongst some quarters it was almost acceptable to be a part of the “skeleton army” that shadowed and terrorised the Salvationists. In 1890, a report on a meeting in Launceston reveals the challenges that were faced:

“After tea an extensive torchlight procession paraded the town, headed by the full brass band, and on their return to the barracks a public meeting was held, at which about 800 were present…. During the meeting Colonel Pollard gave an address, in which he referred to the difficulties the army had to overcome…they had tried the “prison trick” to hinder the work. In Hobart there were people opposed to the army, and when a certain Mayor came into office he concluded that though similar processions had been allowed for six or seven years he would now put a stop to them, and the result had been that Captain Gallagher had had to serve fourteen days in prison…”

The Daily Telegraph's report concluded with the line:

“The larrikins outside the building broke a few windows and otherwise amused themselves during the address”.

Another article appearing in the Daily Telegraphy in 1887 gave the following advice to the Salvation Army:

“Unless the Army can control the ruder parts of their audiences, and the leading officers have the strength of character sufficient to over-balance this disturbing element, meetings for religious purposes are of no avail, and had better be discontinued. The good intensions of the Army have been frustrated in the country districts by the weakness, inexperience, and want of tact of new officers. ...In the country districts the larrikin element is less under the control of the police than in our town, and disturbances have taken place, and noisy scenes have been enacted, which have disgusted many peace-abiding persons with the very name of the Salvation Army, and lowered its character in they eyes of the community…’

As late as 1901, the problem in county areas still seemed to be rife. The Telegraph commented that in Lilydale:

“It is nearly time that something was done to stop the larrikinism that is becoming such a nuisance….. Last Sunday night a number of young fellows killed some fowls that were roosting in a hedge. On being moved on by a resident, they went to the Salvation Army Barracks, throwing stones on the roof, and as a wind-up placed a log of wood against the door, so that anyone opening it from the inside would receive the full force of the blow….”

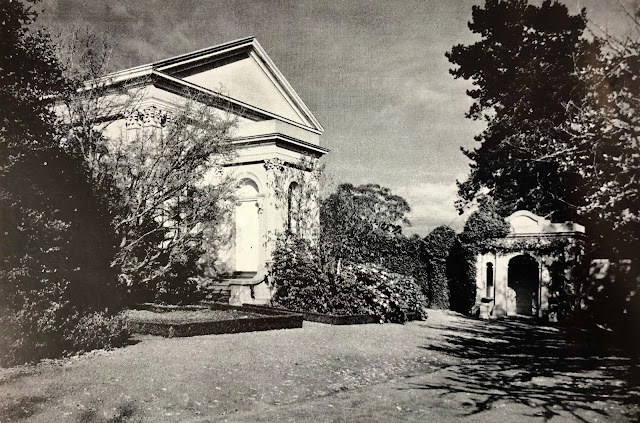

After the turn of the century, the Salvation Army became an established force in Launceston, with citadels in Elizabeth Street and at Invermay. The Galvin Street Citadel had been established in the early 1920’s to serve the South Launceston area. However, by the late 1930’s it had become too small and a decision was made to replace it with a brick building. The original timber hall was shifted to the rear of the Galvin Street site to be used as a ‘young peoples hall and band room’.

The Examiner reported on the opening of the new citadel in April 1943:

“A dream of 20 years was realised on Saturday afternoon when Commissioner W. R. Dalziel turned the key in the front door of the new Salvation Army Citadel in Galvin Street…and declared the building open to “the glory of God and for the salvation of the people.” The commander in his address to the Salvation Army soldiers expressed a wish that not only would the citadel become a hallowed place of worship, but also the rallying centre for aggressive Salvation Army endeavour throughout the district….Mr Dalziel urged Salvationists to be uncompromising in their attitude to present evils and to fight stoutly in upholding the sanctity of the Sabbath Day, and against all the inroads which a world gone clearly astray would seek to make upon the bulwarks of the Christian faith".

By the 1940’s the Salvation Army had turned a corner in the way it was perceived and the work that it undertook in the community:

“After 1945 the Salvation Army responded to new social problems by extending its services into assisting the homeless, missing persons, drug, gambling and alcohol abuse, disability and migrant services, employment and aged accommodation, and helped in emergencies like the 1967 bushfires”.(2)

"The Salvation Army had a seminal link with Tasmania. Launceston businessman and philanthropist Henry Reed, living in London, gave William Booth over £5000 to establish the Salvation Army on a firm footing in about 1870. In 1883 the Salvation Army Launceston Corps began operating, and corps were formed in Hobart, Latrobe, Waratah and other towns. Marches by these 'militant servants of Christ' through the two main cities with loud music attracted the larrikin element or 'roughs', who exploded flour bombs in the Salvationists' faces or threw mud and beer. Some Salvationists were arrested for marching without permission or refusing to desist from making excessive noise”.(1)

A survey of the press in Launceston during this time reveals that the ‘Army’ experienced significant opposition and harassment in the town up until the time its founder, General Booth, visited Launceston in 1891. In 1883, the year that the ‘Army’ was established in Launceston, a correspondent to the Daily Telegraph wrote:

“I see, …in your valuable paper this morning, that the larrikin element is spoken of as causing a disturbance in the Wesleyan Schoolroom last night, at a meeting of the Salvation Army. But sir, it was not those that are looked upon by the public as the larrikin class, but a few young men respectably dressed and holding places of trust in town. They were some of these who caused the most disturbance by shouting and trying to sing. Their conduct is disgraceful. Their names are well known….”

Amongst some quarters it was almost acceptable to be a part of the “skeleton army” that shadowed and terrorised the Salvationists. In 1890, a report on a meeting in Launceston reveals the challenges that were faced:

“After tea an extensive torchlight procession paraded the town, headed by the full brass band, and on their return to the barracks a public meeting was held, at which about 800 were present…. During the meeting Colonel Pollard gave an address, in which he referred to the difficulties the army had to overcome…they had tried the “prison trick” to hinder the work. In Hobart there were people opposed to the army, and when a certain Mayor came into office he concluded that though similar processions had been allowed for six or seven years he would now put a stop to them, and the result had been that Captain Gallagher had had to serve fourteen days in prison…”

The Daily Telegraph's report concluded with the line:

“The larrikins outside the building broke a few windows and otherwise amused themselves during the address”.

Another article appearing in the Daily Telegraphy in 1887 gave the following advice to the Salvation Army:

“Unless the Army can control the ruder parts of their audiences, and the leading officers have the strength of character sufficient to over-balance this disturbing element, meetings for religious purposes are of no avail, and had better be discontinued. The good intensions of the Army have been frustrated in the country districts by the weakness, inexperience, and want of tact of new officers. ...In the country districts the larrikin element is less under the control of the police than in our town, and disturbances have taken place, and noisy scenes have been enacted, which have disgusted many peace-abiding persons with the very name of the Salvation Army, and lowered its character in they eyes of the community…’

As late as 1901, the problem in county areas still seemed to be rife. The Telegraph commented that in Lilydale:

“It is nearly time that something was done to stop the larrikinism that is becoming such a nuisance….. Last Sunday night a number of young fellows killed some fowls that were roosting in a hedge. On being moved on by a resident, they went to the Salvation Army Barracks, throwing stones on the roof, and as a wind-up placed a log of wood against the door, so that anyone opening it from the inside would receive the full force of the blow….”

After the turn of the century, the Salvation Army became an established force in Launceston, with citadels in Elizabeth Street and at Invermay. The Galvin Street Citadel had been established in the early 1920’s to serve the South Launceston area. However, by the late 1930’s it had become too small and a decision was made to replace it with a brick building. The original timber hall was shifted to the rear of the Galvin Street site to be used as a ‘young peoples hall and band room’.

The Examiner reported on the opening of the new citadel in April 1943:

“A dream of 20 years was realised on Saturday afternoon when Commissioner W. R. Dalziel turned the key in the front door of the new Salvation Army Citadel in Galvin Street…and declared the building open to “the glory of God and for the salvation of the people.” The commander in his address to the Salvation Army soldiers expressed a wish that not only would the citadel become a hallowed place of worship, but also the rallying centre for aggressive Salvation Army endeavour throughout the district….Mr Dalziel urged Salvationists to be uncompromising in their attitude to present evils and to fight stoutly in upholding the sanctity of the Sabbath Day, and against all the inroads which a world gone clearly astray would seek to make upon the bulwarks of the Christian faith".

By the 1940’s the Salvation Army had turned a corner in the way it was perceived and the work that it undertook in the community:

“After 1945 the Salvation Army responded to new social problems by extending its services into assisting the homeless, missing persons, drug, gambling and alcohol abuse, disability and migrant services, employment and aged accommodation, and helped in emergencies like the 1967 bushfires”.(2)

The Galvin Street Citadel has long closed but it is a reminder of the early days of the Salvation Army in Launceston. Future blog entries on the Elizabeth Street Citadel and the Invermay Citadel will cover other aspects of the Salvation army such as Booth's visit to Launceston in 1891 and the issue of poverty in the city.

|

| Photograph: Duncan Grant 2018 |

|

| The word 'CITADEL' can still be made out. Photograph: Duncan Grant 2018 |

|

| Photograph: Duncan Grant 2018 |

|

| Photograph: Duncan Grant 2018 |

|

| Photograph: Duncan Grant 2018 |

Sources:

Daily Telegraph Thursday 25 October 1883, page 3

Daily Telegraph Saturday 30 July 1887, page 1

Launceston Examiner Wednesday 5 March 1890, page 3

Daily Telegraph Saturday 6 July 1901, page 10

Examiner Tuesday 11 November 1941, page 4

Examiner Monday 28 April 1941, page 4

Examiner Monday 20 April 1942, page 4

Examiner Friday 17 April 1942, page 4

(1)http://www.utas.edu.au/library/companion_to_tasmanian_history/S/Salvation%20army.htm (accessed 29/4/18)

(2)http://www.salvationarmy.org.au/en/Who-We-Are/History-and-heritage/1880---1900/ (accessed 29/4/18)

http://www.salvationarmy.org.au/en/Who-We-Are/History-and-heritage/1880---1900/ (accessed 29/4/18)

Comments

Post a Comment