No. 192 - St Patrick's at Latrobe (Part 2) - Treason, a Double Funeral and a Bull

The early history of St Patrick’s at Latrobe can be illuminated through the lives of three remarkable individuals. The first is Father James Noone; or “James the builder”, who established the church at Latrobe as well other Catholic churches across the Northwest. The second is Father T.J. O’ Donnell, a charismatic and controversial priest who was not afraid of challenging authority. The third is Sister Agnes, one of the pioneering Sisters’ of Mercy who opened the Orders first convent at St Patrick’s. In this second part of story of St Patrick’s the spotlight falls on Father Thomas Joseph O’Donnell.

Thomas Joseph O'Donnell was born on 3 August 1876 in Victoria, the fourth of seven children of Irish parents. Recognised as a man of exceptional ability, Archbishop Murphy of Tasmania sent him to study at All Hallows College, Dublin. After he was ordained in 1907 he returned to Tasmania as an assistant priest at St Patrick’s Latrobe. He moved to to Stanley in 1909 where he promoted church-building and local issues. In 1915 he officiated, at the request of Enid Burnell, at her marriage to Joseph Lyons, Australia’s only Tasmanian Prime Minister.

In February 1918 O'Donnell created a sensation by joining the Australian Imperial Force as a chaplain with the rank of captain. He embarked on a speaking tour in support of conscription before he served in France with the 11th Battalion. In October 1919 O'Donnell was arrested in Ireland for traitorous and disloyal language concerning the King and British policy in Ireland. He also stated that Germany would have won the war had it not been for the A.I.F. He was held in Dublin before being removed to Britain for trial. Prime Minister ‘Billy’ Hughes wrote protests to the British government and messages of support of O'Donnell while Winston Churchill responded to the matter in the House of Commons.

In an interview published by The Advocate in 1933, Father O’ Donnell recounts his version of this bizarre episode in Australian history:

“In Tasmania” said Father O’Donnell, I came into possession of a pistol; which had once belonged to the famous Irish patriot John Mitchell, who was transported to Tasmania for taking part in an uprising in Ireland in the middle of the last century. Mitchell gave the pistol to one of the men who helped him escape to America.

When I went to the war I took the pistol with me, to give it to the National Museum in Dublin as an historic relic. It was that pistol which led to my arrest and my court martial.

In 1919, on leave, I went to Ireland for a holiday. As the country was then in a very disturbed state I had resolved to take part in no public affairs. I wore the uniform of an Australian officer... At that time Lord French, the Lord-Lieutenant, and his advisors feared another rebellion in Ireland, like that of 1916. They had been told, I learnt afterwards, that the leader of this new uprising was to come to Ireland dressed either as a priest or a colonial officer. Dublin was full of secret service agents, both British and Sinn Fein.

I consulted an Irish member of the House of Commons about John Mitchell’s pistol, and decided to give the old and now useless weapon to Mr. Arthur Griffiths, the Sinn Fein leader. A meeting was arranged in a restaurant in Henry Street, Dublin, and there I handed the pistol to Griffiths.

Unknown to me, secret service agents were in the restaurant, and they immediately reported to Dublin Castle that a man dressed as a colonial officer was distributing arms to the head of the Sinn Fein Party.

At Killarney, in the hotel where I stayed, I was having tea on my own one day, when four people who I learnt afterwards, were British spies, came and sat down near me. One of them was an English lieutenant and one a women.

When I returned to Dublin two military police called at my home and told me that I was wanted at the Castle…. The chief of police said it had been reported that I had used the most seditious language in a hotel at Killarney. I denied it, and I was then told that I was under arrest, and was placed under armed guard.

The chief of police, wishing to find out if I really was a chaplain, wired to London. But sent his wire to the Canadian Army instead of the Australian. Of course he received a reply that I was not known, and then he was certain that his spies had captured the man who had come to start a new rebellion.

Next day I was removed to the Richmond Barracks, where all those arrested for taking part in the rebellion of 1915 were imprisoned, and many shot. No one, not even my lawyers or even a clergyman was allowed to talk to me unless a gaol official was present.

After making inquiries the military authorities realised that they had made a big mistake. It was an awkward situation for them, and they didn’t know how to get out of it. Then they published a statement that I had been arrested for a mere neglect of military regulations, and that my arrest was in no way connected with the Irish political situation. It was said also that I would be deported to Australia.

As the news of my arrest had been published both in England and Australia I was not satisfied with such a simple process of allowing the military authorities to be relieved of their difficulty. I wanted to clear my name.

As the Government went ahead with plans for sending me away on a warship I got hold of a very clever Irish lawyer…and between us we worked out a plan which would enable me to delay things long enough for him to get a writ of habeas corpus. Once we had this writ I would have to be granted a trial.

Five minutes before Government emissaries came to take me away he got a writ forbidding the military authorities to remove me from jurisdiction of the Irish High Court. Later the matter came before three judges in the High Court. The military authorities now changed their attitude, and Major-General Shaw, commander of all the forces in Ireland said in court that the charge against me was sedition, in that at Killarney I had denounced the King and the Royal Family, and said that I had come to lead Ireland in a new revolution and free it from English tyranny.

The judges granted the writ, but said in the disturbed state of the country I had better return to England. If there were any inquiry or trial, the British Government would pay my expenses.

Next day I arrived in London under guard, and was taken to the Tower of London. There I was imprisoned under armed guard, in the cell, which Sir Roger Casement, who was executed for his part in an attempted rebellion in Ireland during the war, had occupied.

“I was defended by the famous Tim Healey, late Governor-General of the Irish Free State…. the case caused tremendous interest, and at the end of two days the court granted me an honourable acquittal”.

Writing in 1919, O’ Donnell argued that the whole incident fuelled sectarianism that was rife in Australia and Tasmania at the time. He wrote:

“There are in Tasmania people…who made use of the war to insult Catholics, even though thousands of them were out with me in the hell of battle doing their part along with the boys of every creed. The scandalous attacks made during recent elections and before by the Loyalty League, public men, and newspapers were more than disgusting. They were vile insults to the many thousands of Catholic men who had come out to the fields of battle freely to do their bit. They were insults to the thousands of them who lie sleeping in honoured graves on every field where Australians fought”.

After the ‘Treason Trial’, Father O’ Donnell returned to Tasmania in 1921 where he was given charge of the Latrobe, Sheffield and Railton Parish. During the next eight years he became a well-known supporter of sport on the North West coast, a founder of the North-West Football Union and the Latrobe Cycling Club. He was also a board member of the Spencer Hospital, Wynyard and the Devon Hospital at Latrobe.

It was not long after Father O’ Donnell’s return to Latrobe that he was in the headlines again. This time the issue was a funeral; or more accurately; two funerals. An account of the incident in a Hobart newspaper, The World, perhaps gives the most balanced version of the affair:

“An extraordinary occurrence took place on Monday at the burial at Latrobe of a middle-aged man, Mr Michael Dacey, who died at Devon Hospital on Saturday last. At the request of the relatives of the deceased the Rev. W.R. Jennings, Methodist Minister, conducted the burial service and at its completion, and after the relatives had moved away, the Rev. T.J. O’Donnell …who with a number of adherents had followed the funeral procession, and waited apart in the cemetery, advanced to the grave and conducted the burial service of his Church over the body.

The Rev. T.J. O’ Donnell claimed that the deceased had been a member of his Church; hence the unusual action. It is stated that the relatives of the deceased were strongly opposed to Father O’ Donnell’s proceedings.

Rev. T.J. O’ Donnell gave the following explanation of the case: Dacey died in the Devon Hospital on Saturday. In his last illness he had been attended by Father O’ Donnell, who administered the rites of the Catholic Church to him on Wednesday, having received an urgent message by phone from the hospital to attend to him – He did not hear of his death till late on Sunday night, and yesterday morning sent to the undertaker that the man was a Catholic, and should be buried in the Catholic cemetery with the Catholic service. Mr. Scott the undertaker in question, sent word that the relatives had made arrangements for the burial to take place in the General Cemetery, where Rev. Jennings would read the service. Father O’Donnell rang up Rev. Jennings and told him that the man Dacey was a Catholic and that he had received the rites of the Church last week”.

Relatives insisted on a Protestant service, which bought matters to a head:

“The funeral left the hospital at a quarter to 2, being followed by a few of his friends. When it came near the Catholic Church, the bell there started to toll, and as it passed the main gate the cortege was joined by Father O’ Donnell in his robes. There were with him nearly one hundred members of the Catholic congregation. Rev. Jennings walked ahead of the hearse. Arriving at the cemetery the Catholic contingent remained about fifty yards from the grave while the Methodist service was being read. At the conclusion Father O’ Donnell advanced with his followers to the grave and there read the Catholic service…”

Barely two months later Father O’Donnell was again the subject of news headlines, this time involving the police. In June 1921, a man called Harry Shaw, (a known alcoholic) had arrived at the presbytery asking for money. Rebuffed by O’Donnell, on leaving the presbytery Shaw fell and injured his shoulder. Following the incident O’ Donnell claimed that Sergeant Flude, in company with Detective Harmon, visited Shaw and urged him to take action and informed him that it was “worth £50”. When O’Donnell got wind of this he made a complaint to the Commissioner of Police and asked him to hold a departmental enquiry. The enquiry was covered extensively by Tasmanian newspapers and provides further evidence not only of sectarianism in Latrobe but also bad blood between certain members of the police force and the Catholics of the town.

A final story concerning Father O’ Donnell, while at St Patrick’s, involves a very close encounter with a bull. The details are recorded in the Hobart Mercury:

“A sensational incident occurred at Latrobe this afternoon, by which the Rev. Father T. J. O'Donnell narrowly escaped death or serious injury. A drover named Kay was, with a man named Bowden, driving an animal to the sale yards. At the Catholic Church it entered the grounds through the gate. Kay made an effort to get it out, but it went through, the hawthorn hedge into the presbytery gardens. Father O'Donnell called his gardener to assist in removing the beast, but when an attempt was made to drive it through the presbytery gate to the street it again made its way through the hedge to the churchyard. Father O'Donnell was afraid it might go through the schoolyard to the playground, where the school children were playing, and went out to assist in putting it out between the church and the presbytery, where there is a hedge, and the passage between the hedge and the church is but four feet wide. Father O'Donnell was going through this passage when he saw a dog racing away, and as he came to the corner he saw the bull coming at a great speed. Having no time to escape it either way, Father O'Donnell threw himself flat on the ground, and as near to the hedge as possible, in the hope that the bull would pass on. But when the animal came near it stopped, sniffed, and drove its horns into Father O'Donnell's clothing and tossed him into the air. The animal then kicked at him and continued on his way.

Father O'Donnell was wearing a soutane [cassock] at the time, and this helped in a measure to save him: but it was torn up in shreds, as well as his trousers and underclothing.

Mr F. J. Matthews was passing, and he heard shouts. He rushed across, and found Father O'Donnell on the ground suffering from shock. Drs’. Walpole and Bean were summoned, and on examination found that the horn of the animal had inflicted a wound on Father O'Donnell's leg about six inches long, but it was not serious. There were cuts on the head and face, and the thumbs were dislocated. Fortunately, no bones were broken. It was only the fact that he had shown presence of mind in throwing himself to the ground that saved Father O'Donnell from serious injury. The horns of the beast were remarkably long and sharp. Constable Webberly was summoned, and took particulars, with a view to proceedings. The bull, after the incident, could not be dislodged, and threw itself down in the presbytery gardens. Several other men were sent for, and after some trouble the beast was driven through a back way to the street”.

Having survived a bull in 1924 and also a fire in the presbytery in 1926, Father O’ Donnell left St Patrick’s for New Norfolk in 1929 and shortly after became the first parish priest of the Church of St Therese of Lisieux at Moonah in 1931. Here O' Donnell was involved in further controversy with the establishment but this will be covered in a later article on the Moonah church.

Historian Leslie Robson probably best sums up the character of Father Thomas Joseph O'Donnell “as one who stood for the under-dog and who also believed that there were two sides to every question—his and the wrong one”.

Thomas Joseph O'Donnell was born on 3 August 1876 in Victoria, the fourth of seven children of Irish parents. Recognised as a man of exceptional ability, Archbishop Murphy of Tasmania sent him to study at All Hallows College, Dublin. After he was ordained in 1907 he returned to Tasmania as an assistant priest at St Patrick’s Latrobe. He moved to to Stanley in 1909 where he promoted church-building and local issues. In 1915 he officiated, at the request of Enid Burnell, at her marriage to Joseph Lyons, Australia’s only Tasmanian Prime Minister.

In February 1918 O'Donnell created a sensation by joining the Australian Imperial Force as a chaplain with the rank of captain. He embarked on a speaking tour in support of conscription before he served in France with the 11th Battalion. In October 1919 O'Donnell was arrested in Ireland for traitorous and disloyal language concerning the King and British policy in Ireland. He also stated that Germany would have won the war had it not been for the A.I.F. He was held in Dublin before being removed to Britain for trial. Prime Minister ‘Billy’ Hughes wrote protests to the British government and messages of support of O'Donnell while Winston Churchill responded to the matter in the House of Commons.

In an interview published by The Advocate in 1933, Father O’ Donnell recounts his version of this bizarre episode in Australian history:

“In Tasmania” said Father O’Donnell, I came into possession of a pistol; which had once belonged to the famous Irish patriot John Mitchell, who was transported to Tasmania for taking part in an uprising in Ireland in the middle of the last century. Mitchell gave the pistol to one of the men who helped him escape to America.

When I went to the war I took the pistol with me, to give it to the National Museum in Dublin as an historic relic. It was that pistol which led to my arrest and my court martial.

In 1919, on leave, I went to Ireland for a holiday. As the country was then in a very disturbed state I had resolved to take part in no public affairs. I wore the uniform of an Australian officer... At that time Lord French, the Lord-Lieutenant, and his advisors feared another rebellion in Ireland, like that of 1916. They had been told, I learnt afterwards, that the leader of this new uprising was to come to Ireland dressed either as a priest or a colonial officer. Dublin was full of secret service agents, both British and Sinn Fein.

I consulted an Irish member of the House of Commons about John Mitchell’s pistol, and decided to give the old and now useless weapon to Mr. Arthur Griffiths, the Sinn Fein leader. A meeting was arranged in a restaurant in Henry Street, Dublin, and there I handed the pistol to Griffiths.

Unknown to me, secret service agents were in the restaurant, and they immediately reported to Dublin Castle that a man dressed as a colonial officer was distributing arms to the head of the Sinn Fein Party.

At Killarney, in the hotel where I stayed, I was having tea on my own one day, when four people who I learnt afterwards, were British spies, came and sat down near me. One of them was an English lieutenant and one a women.

When I returned to Dublin two military police called at my home and told me that I was wanted at the Castle…. The chief of police said it had been reported that I had used the most seditious language in a hotel at Killarney. I denied it, and I was then told that I was under arrest, and was placed under armed guard.

The chief of police, wishing to find out if I really was a chaplain, wired to London. But sent his wire to the Canadian Army instead of the Australian. Of course he received a reply that I was not known, and then he was certain that his spies had captured the man who had come to start a new rebellion.

Next day I was removed to the Richmond Barracks, where all those arrested for taking part in the rebellion of 1915 were imprisoned, and many shot. No one, not even my lawyers or even a clergyman was allowed to talk to me unless a gaol official was present.

After making inquiries the military authorities realised that they had made a big mistake. It was an awkward situation for them, and they didn’t know how to get out of it. Then they published a statement that I had been arrested for a mere neglect of military regulations, and that my arrest was in no way connected with the Irish political situation. It was said also that I would be deported to Australia.

As the news of my arrest had been published both in England and Australia I was not satisfied with such a simple process of allowing the military authorities to be relieved of their difficulty. I wanted to clear my name.

As the Government went ahead with plans for sending me away on a warship I got hold of a very clever Irish lawyer…and between us we worked out a plan which would enable me to delay things long enough for him to get a writ of habeas corpus. Once we had this writ I would have to be granted a trial.

Five minutes before Government emissaries came to take me away he got a writ forbidding the military authorities to remove me from jurisdiction of the Irish High Court. Later the matter came before three judges in the High Court. The military authorities now changed their attitude, and Major-General Shaw, commander of all the forces in Ireland said in court that the charge against me was sedition, in that at Killarney I had denounced the King and the Royal Family, and said that I had come to lead Ireland in a new revolution and free it from English tyranny.

The judges granted the writ, but said in the disturbed state of the country I had better return to England. If there were any inquiry or trial, the British Government would pay my expenses.

Next day I arrived in London under guard, and was taken to the Tower of London. There I was imprisoned under armed guard, in the cell, which Sir Roger Casement, who was executed for his part in an attempted rebellion in Ireland during the war, had occupied.

“I was defended by the famous Tim Healey, late Governor-General of the Irish Free State…. the case caused tremendous interest, and at the end of two days the court granted me an honourable acquittal”.

Writing in 1919, O’ Donnell argued that the whole incident fuelled sectarianism that was rife in Australia and Tasmania at the time. He wrote:

“There are in Tasmania people…who made use of the war to insult Catholics, even though thousands of them were out with me in the hell of battle doing their part along with the boys of every creed. The scandalous attacks made during recent elections and before by the Loyalty League, public men, and newspapers were more than disgusting. They were vile insults to the many thousands of Catholic men who had come out to the fields of battle freely to do their bit. They were insults to the thousands of them who lie sleeping in honoured graves on every field where Australians fought”.

After the ‘Treason Trial’, Father O’ Donnell returned to Tasmania in 1921 where he was given charge of the Latrobe, Sheffield and Railton Parish. During the next eight years he became a well-known supporter of sport on the North West coast, a founder of the North-West Football Union and the Latrobe Cycling Club. He was also a board member of the Spencer Hospital, Wynyard and the Devon Hospital at Latrobe.

It was not long after Father O’ Donnell’s return to Latrobe that he was in the headlines again. This time the issue was a funeral; or more accurately; two funerals. An account of the incident in a Hobart newspaper, The World, perhaps gives the most balanced version of the affair:

“An extraordinary occurrence took place on Monday at the burial at Latrobe of a middle-aged man, Mr Michael Dacey, who died at Devon Hospital on Saturday last. At the request of the relatives of the deceased the Rev. W.R. Jennings, Methodist Minister, conducted the burial service and at its completion, and after the relatives had moved away, the Rev. T.J. O’Donnell …who with a number of adherents had followed the funeral procession, and waited apart in the cemetery, advanced to the grave and conducted the burial service of his Church over the body.

The Rev. T.J. O’ Donnell claimed that the deceased had been a member of his Church; hence the unusual action. It is stated that the relatives of the deceased were strongly opposed to Father O’ Donnell’s proceedings.

Rev. T.J. O’ Donnell gave the following explanation of the case: Dacey died in the Devon Hospital on Saturday. In his last illness he had been attended by Father O’ Donnell, who administered the rites of the Catholic Church to him on Wednesday, having received an urgent message by phone from the hospital to attend to him – He did not hear of his death till late on Sunday night, and yesterday morning sent to the undertaker that the man was a Catholic, and should be buried in the Catholic cemetery with the Catholic service. Mr. Scott the undertaker in question, sent word that the relatives had made arrangements for the burial to take place in the General Cemetery, where Rev. Jennings would read the service. Father O’Donnell rang up Rev. Jennings and told him that the man Dacey was a Catholic and that he had received the rites of the Church last week”.

Relatives insisted on a Protestant service, which bought matters to a head:

“The funeral left the hospital at a quarter to 2, being followed by a few of his friends. When it came near the Catholic Church, the bell there started to toll, and as it passed the main gate the cortege was joined by Father O’ Donnell in his robes. There were with him nearly one hundred members of the Catholic congregation. Rev. Jennings walked ahead of the hearse. Arriving at the cemetery the Catholic contingent remained about fifty yards from the grave while the Methodist service was being read. At the conclusion Father O’ Donnell advanced with his followers to the grave and there read the Catholic service…”

Barely two months later Father O’Donnell was again the subject of news headlines, this time involving the police. In June 1921, a man called Harry Shaw, (a known alcoholic) had arrived at the presbytery asking for money. Rebuffed by O’Donnell, on leaving the presbytery Shaw fell and injured his shoulder. Following the incident O’ Donnell claimed that Sergeant Flude, in company with Detective Harmon, visited Shaw and urged him to take action and informed him that it was “worth £50”. When O’Donnell got wind of this he made a complaint to the Commissioner of Police and asked him to hold a departmental enquiry. The enquiry was covered extensively by Tasmanian newspapers and provides further evidence not only of sectarianism in Latrobe but also bad blood between certain members of the police force and the Catholics of the town.

A final story concerning Father O’ Donnell, while at St Patrick’s, involves a very close encounter with a bull. The details are recorded in the Hobart Mercury:

“A sensational incident occurred at Latrobe this afternoon, by which the Rev. Father T. J. O'Donnell narrowly escaped death or serious injury. A drover named Kay was, with a man named Bowden, driving an animal to the sale yards. At the Catholic Church it entered the grounds through the gate. Kay made an effort to get it out, but it went through, the hawthorn hedge into the presbytery gardens. Father O'Donnell called his gardener to assist in removing the beast, but when an attempt was made to drive it through the presbytery gate to the street it again made its way through the hedge to the churchyard. Father O'Donnell was afraid it might go through the schoolyard to the playground, where the school children were playing, and went out to assist in putting it out between the church and the presbytery, where there is a hedge, and the passage between the hedge and the church is but four feet wide. Father O'Donnell was going through this passage when he saw a dog racing away, and as he came to the corner he saw the bull coming at a great speed. Having no time to escape it either way, Father O'Donnell threw himself flat on the ground, and as near to the hedge as possible, in the hope that the bull would pass on. But when the animal came near it stopped, sniffed, and drove its horns into Father O'Donnell's clothing and tossed him into the air. The animal then kicked at him and continued on his way.

Father O'Donnell was wearing a soutane [cassock] at the time, and this helped in a measure to save him: but it was torn up in shreds, as well as his trousers and underclothing.

Mr F. J. Matthews was passing, and he heard shouts. He rushed across, and found Father O'Donnell on the ground suffering from shock. Drs’. Walpole and Bean were summoned, and on examination found that the horn of the animal had inflicted a wound on Father O'Donnell's leg about six inches long, but it was not serious. There were cuts on the head and face, and the thumbs were dislocated. Fortunately, no bones were broken. It was only the fact that he had shown presence of mind in throwing himself to the ground that saved Father O'Donnell from serious injury. The horns of the beast were remarkably long and sharp. Constable Webberly was summoned, and took particulars, with a view to proceedings. The bull, after the incident, could not be dislodged, and threw itself down in the presbytery gardens. Several other men were sent for, and after some trouble the beast was driven through a back way to the street”.

Having survived a bull in 1924 and also a fire in the presbytery in 1926, Father O’ Donnell left St Patrick’s for New Norfolk in 1929 and shortly after became the first parish priest of the Church of St Therese of Lisieux at Moonah in 1931. Here O' Donnell was involved in further controversy with the establishment but this will be covered in a later article on the Moonah church.

Historian Leslie Robson probably best sums up the character of Father Thomas Joseph O'Donnell “as one who stood for the under-dog and who also believed that there were two sides to every question—his and the wrong one”.

The first part of the St Patrick's story can be found on this LINK:

|

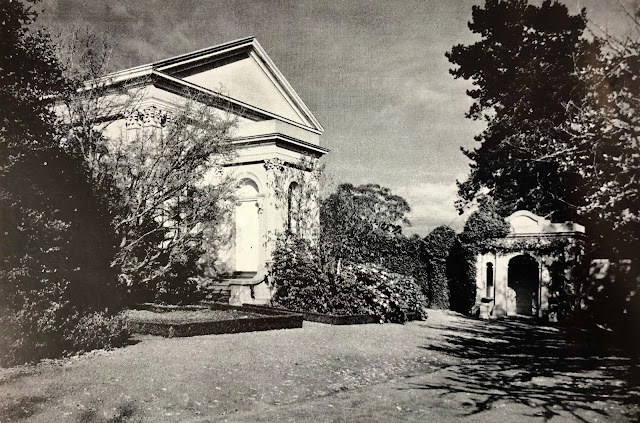

| Photograph: Duncan Grant 2018 |

|

| Photograph: Duncan Grant 2018 |

|

| Photograph: Duncan Grant 2018 |

|

| Photograph: Duncan Grant 2018 |

|

| Father O' Donnell's headstone at Cornelian Bay Cemetery - Thanks to Gravesites Of Tasmania. |

Father O' Donnell - In the Headlines

Sources:

The Advocate Monday 1 December 1919, page 3

The Daily Telegraph Monday 17 May 1920, page 8

The Mercury Tuesday 28 June 1921, page 5

The Daily Telegraph Wednesday 29 June 1921, page 2

The Advocate Tuesday 28 June 1921, page 2

The World Thursday 30 June 1921, page 2

The Advocate Saturday 16 July 1921, page 5

The Advocate Monday 25 July 1921, page 3

The Mercury Tuesday 26 July 1921, page 6

The Advocate Wednesday 27 July 1921, page 2

The Daily Telegraph Wednesday 27 July 1921, page 7

The Mercury Wednesday 27 July 1921, page 7

The Examiner Friday 26 August 1921, page 8

The Examiner Saturday 27 August 1921, page 9

The Advocate Saturday 27 August 1921, page 4

The Mercury Saturday 27 August 1921, page 10

The Daily Telegraph Saturday 27 August 1921, page 8

The Mercury Tuesday 12 August 1924, page 6

The Advocate Thursday 18 March 1926, page 4

The Advocate Monday 7 January 1929, page 2

The Advocate Tuesday 7 March 1933, page 2

The Advocate Monday 5 September 1949, page 4

http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/odonnell-thomas-joseph-7880

https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1919/dec/02/captain-rev-t-j-odonnell-court-martial

http://www.gravesoftas.com.au/Cornelian%20Bay%20Live/Cornelian_Bay_Entry.htm

Southerwood, W. T Planting a faith in Tasmania. Southerwood, Hobart, 1970.

The Daily Telegraph Monday 17 May 1920, page 8

The Mercury Tuesday 28 June 1921, page 5

The Daily Telegraph Wednesday 29 June 1921, page 2

The Advocate Tuesday 28 June 1921, page 2

The World Thursday 30 June 1921, page 2

The Advocate Saturday 16 July 1921, page 5

The Advocate Monday 25 July 1921, page 3

The Mercury Tuesday 26 July 1921, page 6

The Advocate Wednesday 27 July 1921, page 2

The Daily Telegraph Wednesday 27 July 1921, page 7

The Mercury Wednesday 27 July 1921, page 7

The Examiner Friday 26 August 1921, page 8

The Examiner Saturday 27 August 1921, page 9

The Advocate Saturday 27 August 1921, page 4

The Mercury Saturday 27 August 1921, page 10

The Daily Telegraph Saturday 27 August 1921, page 8

The Mercury Tuesday 12 August 1924, page 6

The Advocate Thursday 18 March 1926, page 4

The Advocate Monday 7 January 1929, page 2

The Advocate Tuesday 7 March 1933, page 2

The Advocate Monday 5 September 1949, page 4

http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/odonnell-thomas-joseph-7880

https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1919/dec/02/captain-rev-t-j-odonnell-court-martial

http://www.gravesoftas.com.au/Cornelian%20Bay%20Live/Cornelian_Bay_Entry.htm

Southerwood, W. T Planting a faith in Tasmania. Southerwood, Hobart, 1970.

Comments

Post a Comment