No. 312 - St Matthew's at Glenorchy - "A System of Arrogance"

When the foundation stone of St Matthew’s, (or the Scots Church, as it was originally called), was laid in 1839, The Colonial Times described the site at O’ Brien’s Bridge as a “retired and secluded locality”. Since then, O’Brien’s Bridge has grown into the city of Glenorchy and St Matthew’s location could not be more incongruous as it borders on a busy bus terminus in the midst of a shopping strip.

From the beginning their was strong opposition from the Anglican hierarchy to the establishment of a Presbyterian church at O’ Brien’s Bridge. In the early part of the nineteenth century the government treated the Church of England as the colony's ‘official’ established religion. This changed somewhat with the passage of the 1837 ‘Church Act’, which enabled the Church of England, the Roman Catholic Church and the Presbyterian Church, access to a structured and consistent system of government funding. Some in the Anglican Church resented this development.

In 1839 the Colonial Times reported:

“… The Presbyterians at, and in the vicinity of O’Brien’s Bridge, had prepared a requisition, praying the Government to erect a church, and, of course, undertaking, … to furnish their portion of the funds, required for such a purpose. Now, will it be believed that one [Reverend] Mr. Swayne, … has been most industriously active in persuading persons not to sign the requisition, and even, has actually strived to seduce some, who had already signed, to withdraw their names!"

The Colonial Times further charged that:

“A system of arrogance, nay, even of persecution, appears to be unsparingly and sedulously adopted towards the members of every other persuasion; and various petty and paltry manoeuvres are put into practice to maintain and advance the high standing, and dominant character of “good old Mother Church.” If these high prelatic priests would but reflect upon the consequence of this overbearing and repulsive conduct, they would, in pursuance with the reason, with which, we presume they are endowed, avoid most sedulously every proceeding, that might tend to offend or irritate, first, sectarians, and, secondly, the public at large”.

In a similar vein, Launceston's Cornwall Chronicle complained that the Presbyterian's request for government financial assistance under the Church Act “did not ….please the dominant Church System party” and that they had been:

“…Using every means to induce the inhabitants to stultify themselves, by withdrawing their names from the Presbyterian requisition, and to attach them to a requisition for an Episcopal Church”.

The Chronicle alleged:

“Two individuals, …were very active in their endeavours to persuade the inhabitants to withdraw their names; they succeeded, however, we believe, only in one instance, and that after much persuasion, if not misrepresentation, of their object…”.

Despite the “Episcopalian manoeuvring” as the Colonial Times put it, the Presbyterians received the necessary funding and the Governor, Sir John Franklin, laid the foundation stone for the Scots Church on Friday 20th December 1839. Speaking at the ceremony it is evident that Franklin was at pains to diminish the recent sectarian rivalry. Franklin remarked:

“The Church of Scotland held the same doctrines, and taught the same truths with the Church of which he was a zealous and attached member, and though the two Churches differed in some points, yet their difference was as to matters of subordinate and comparatively trifling importance. Both taught the same great and fundamental doctrines of the Christian faith…”

The correspondent for the Colonial Times noted:

“…Nothing could be more gratifying than the attendance and attention of the numerous inhabitants of the district on this occasion. Many, very many persons took an interest in the ceremony, which convinced us they placed a deep importance on the establishment of a place of solemn worship, in their retired and secluded locality….”

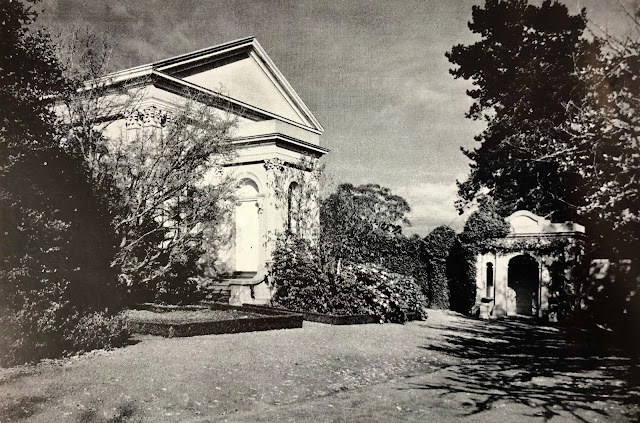

The church was built using convict labour and was completed and opened in November 1841. The 'grand design' of the church was extensively critiqued by the correspondent for the Hobart Courier:

“This edifice was last Sunday week opened for public worship by the Rev. J. Lillie. A collection was afterwards made in aid of the funds of the church, which, we regret to find, are still in arrears…. The church is of dressed freestone, in the Norman style of architecture, with a square tower, which is placed at one of the angles of the body – not in the centre as is customary. It does not appear to us that there is anything incongruous in this, however much it may be opposed to custom – on the contrary, as it is beyond doubt that perfect uniformity of figure in small buildings tends to produce an air of formality, we think the architect commendable for having disregarded established principles. On the whole we admire the building, and hope to see many similar reared for the same purpose and with the same good taste. The style appears to us to produce, by a few very simple forms, considerable architectural effect; and, what is of still greater importance, it produces an expression of the purpose to which the building is devoted, in a manner more piquant than any other of the several styles of the Gothic architecture. This is another of Mr. Blackburn’s works… the cost of the whole was about £1500, of which the Government contributed a considerable sum under the provisions of the Church Act”.

The first minister for St Matthew’s was the Reverend Charles Simson who arrived in 1841 and remained as minister until 1870. In the following year the church was renamed St Matthew’s. In 1904 the church's cemetery was closed and in 1954 the headstones were relocated to the church’s perimeter when the land in front of the church was acquired by the city council to widen the main road. The early twentieth century saw challenging times for St Matthew’s, with a rapid succession of ministers, attempted amalgamations and dwindling numbers making the sustainability of the church difficult. In the 1970’s, St Matthew’s became a part of the Uniting Church and the congregation moved to the Glenorchy Methodist Church. It ceased being used as a church in the year 2000. In 2006 it was restored by the Glenorchy City Council as the potential to be the premier heritage icon in the Glenorchy CBD.

Sources:

Tasmanian, Friday 23 August 1839, page 4

The Cornwall Chronicle, Saturday 24 August 1839, page 1

Colonial Times, Tuesday 27 August 1839, page 4

Colonial Times, Tuesday 5 November 1839, page 7

Colonial Times, Tuesday 17 December 1839, page 8

Colonial Times Tuesday 24 December 1839, page 6

The Courier, Friday 19 November 1841, page 2

From the beginning their was strong opposition from the Anglican hierarchy to the establishment of a Presbyterian church at O’ Brien’s Bridge. In the early part of the nineteenth century the government treated the Church of England as the colony's ‘official’ established religion. This changed somewhat with the passage of the 1837 ‘Church Act’, which enabled the Church of England, the Roman Catholic Church and the Presbyterian Church, access to a structured and consistent system of government funding. Some in the Anglican Church resented this development.

In 1839 the Colonial Times reported:

“… The Presbyterians at, and in the vicinity of O’Brien’s Bridge, had prepared a requisition, praying the Government to erect a church, and, of course, undertaking, … to furnish their portion of the funds, required for such a purpose. Now, will it be believed that one [Reverend] Mr. Swayne, … has been most industriously active in persuading persons not to sign the requisition, and even, has actually strived to seduce some, who had already signed, to withdraw their names!"

The Colonial Times further charged that:

“A system of arrogance, nay, even of persecution, appears to be unsparingly and sedulously adopted towards the members of every other persuasion; and various petty and paltry manoeuvres are put into practice to maintain and advance the high standing, and dominant character of “good old Mother Church.” If these high prelatic priests would but reflect upon the consequence of this overbearing and repulsive conduct, they would, in pursuance with the reason, with which, we presume they are endowed, avoid most sedulously every proceeding, that might tend to offend or irritate, first, sectarians, and, secondly, the public at large”.

In a similar vein, Launceston's Cornwall Chronicle complained that the Presbyterian's request for government financial assistance under the Church Act “did not ….please the dominant Church System party” and that they had been:

“…Using every means to induce the inhabitants to stultify themselves, by withdrawing their names from the Presbyterian requisition, and to attach them to a requisition for an Episcopal Church”.

The Chronicle alleged:

“Two individuals, …were very active in their endeavours to persuade the inhabitants to withdraw their names; they succeeded, however, we believe, only in one instance, and that after much persuasion, if not misrepresentation, of their object…”.

Despite the “Episcopalian manoeuvring” as the Colonial Times put it, the Presbyterians received the necessary funding and the Governor, Sir John Franklin, laid the foundation stone for the Scots Church on Friday 20th December 1839. Speaking at the ceremony it is evident that Franklin was at pains to diminish the recent sectarian rivalry. Franklin remarked:

“The Church of Scotland held the same doctrines, and taught the same truths with the Church of which he was a zealous and attached member, and though the two Churches differed in some points, yet their difference was as to matters of subordinate and comparatively trifling importance. Both taught the same great and fundamental doctrines of the Christian faith…”

The correspondent for the Colonial Times noted:

“…Nothing could be more gratifying than the attendance and attention of the numerous inhabitants of the district on this occasion. Many, very many persons took an interest in the ceremony, which convinced us they placed a deep importance on the establishment of a place of solemn worship, in their retired and secluded locality….”

The church was built using convict labour and was completed and opened in November 1841. The 'grand design' of the church was extensively critiqued by the correspondent for the Hobart Courier:

“This edifice was last Sunday week opened for public worship by the Rev. J. Lillie. A collection was afterwards made in aid of the funds of the church, which, we regret to find, are still in arrears…. The church is of dressed freestone, in the Norman style of architecture, with a square tower, which is placed at one of the angles of the body – not in the centre as is customary. It does not appear to us that there is anything incongruous in this, however much it may be opposed to custom – on the contrary, as it is beyond doubt that perfect uniformity of figure in small buildings tends to produce an air of formality, we think the architect commendable for having disregarded established principles. On the whole we admire the building, and hope to see many similar reared for the same purpose and with the same good taste. The style appears to us to produce, by a few very simple forms, considerable architectural effect; and, what is of still greater importance, it produces an expression of the purpose to which the building is devoted, in a manner more piquant than any other of the several styles of the Gothic architecture. This is another of Mr. Blackburn’s works… the cost of the whole was about £1500, of which the Government contributed a considerable sum under the provisions of the Church Act”.

The first minister for St Matthew’s was the Reverend Charles Simson who arrived in 1841 and remained as minister until 1870. In the following year the church was renamed St Matthew’s. In 1904 the church's cemetery was closed and in 1954 the headstones were relocated to the church’s perimeter when the land in front of the church was acquired by the city council to widen the main road. The early twentieth century saw challenging times for St Matthew’s, with a rapid succession of ministers, attempted amalgamations and dwindling numbers making the sustainability of the church difficult. In the 1970’s, St Matthew’s became a part of the Uniting Church and the congregation moved to the Glenorchy Methodist Church. It ceased being used as a church in the year 2000. In 2006 it was restored by the Glenorchy City Council as the potential to be the premier heritage icon in the Glenorchy CBD.

|

| Photograph: Duncan Grant 2018 © |

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

Sources:

Tasmanian, Friday 23 August 1839, page 4

The Cornwall Chronicle, Saturday 24 August 1839, page 1

Colonial Times, Tuesday 27 August 1839, page 4

Colonial Times, Tuesday 5 November 1839, page 7

Colonial Times, Tuesday 17 December 1839, page 8

Colonial Times Tuesday 24 December 1839, page 6

The Courier, Friday 19 November 1841, page 2

Comments

Post a Comment