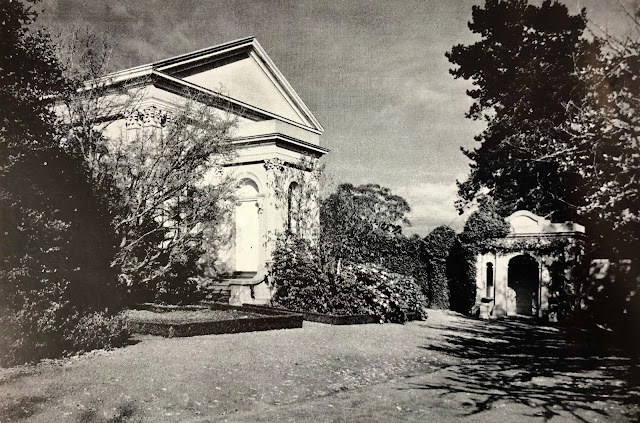

No. 382 - The Ross Female Factory Chapel

The history of the convict system in Tasmania is encyclopedic in its detail. This blog entry will limit itself to providing only general background and some context to the Ross convict chapel. However, a critical point is that for all of the penal system’s notorious brutality, it was in fact a revolutionary system designed to reform the criminal class. As such, religion was an integral part of the penal system in Tasmania and played a critical role in the reform of the convict population. The report for the World Heritage listing of Australia’s convict sites notes that this was achieved through:

“…The construction of churches and chapels for the use of convicts; employment of chaplains at penal stations responsible for the moral improvement of convicts; compulsory attendance at church services; reading of prayers by authorities and ‘private masters’ and distribution of Bibles. Separate churches or rooms were often provided for convicts from different religious denominations. Religious observances were often an essential part of the daily lives of most convicts including those under going secondary punishment. Attendance was rigidly enforced and non-attendance was a punishable offence. Under the probation system, convicts were required to commence and end each day with prayers and attend two divine services on Sundays. Clergymen were critical cogs in the penal machinery, expected to be knowledgeable about the character of each convict. They were required to sign all key documents that could lead to the rehabilitation and freedom of individual convicts including applications for family members to be sent from Britain, tickets-of-leave, special privileges and pardons”.

“…The construction of churches and chapels for the use of convicts; employment of chaplains at penal stations responsible for the moral improvement of convicts; compulsory attendance at church services; reading of prayers by authorities and ‘private masters’ and distribution of Bibles. Separate churches or rooms were often provided for convicts from different religious denominations. Religious observances were often an essential part of the daily lives of most convicts including those under going secondary punishment. Attendance was rigidly enforced and non-attendance was a punishable offence. Under the probation system, convicts were required to commence and end each day with prayers and attend two divine services on Sundays. Clergymen were critical cogs in the penal machinery, expected to be knowledgeable about the character of each convict. They were required to sign all key documents that could lead to the rehabilitation and freedom of individual convicts including applications for family members to be sent from Britain, tickets-of-leave, special privileges and pardons”.

An essential component of the convict system was the ‘female factory’. Female factories were based on British bridewells, prisons and workhouses. They were built for women convicts transported to Tasmania and were called factories because each was a site of production.

Ross is home to one of four female factories in Tasmania, through which approximately 12,000 female convicts were ‘processed’. Ross was established in 1821 as a garrison town and a staging post on the route between Launceston and Hobart. It was also a base for Public Works Parties whose labour produced a number of local buildings and structures such as the famous Ross ‘convict bridge’. A probation station for male convicts was established at the site in 1846 and soon after this it was redeveloped as the Ross Female Factory.

In the 1840’s, landholders in the midlands agitated for the establishment of a female factory closer than the factory situated at Hobart as a source for female servants. The female factory was part of a probation system which was designed to reform the 'inequalities' and problems caused by ‘randomly’ assigning convicts to private settlers. The intention was to promote the passage of women from convict to reputable citizen. In the factories the lives of women were regulated by authority, work, surveillance, religion and finally classification into ‘classes’. After serving six months in the ‘crime class’, approved prisoners, the so-called 'hiring class', became pass holders and could work for wages outside the factory and were able to be acquired by local landowners as servants, or sometimes as wives.

The design and layout of the Ross Female Factory was shaped by its previous use as site for accomodating Public Works Parties and a male probation station. Part of the design of the complex was a chapel which was originally proposed to be located adjacent to the entrance to the station. However, It was relocated to the rear of the site, apparently on the recommendation of Superintendent E.S. Hall (a prominent Catholic) supposedly to facilitate its use by the local Catholic community. It was built on an elevated platform above the surrounding yard. Women were released from their cells and wards to attend services in this building. The drawing on the 1851 plans (see below), reveal that the building resembled a regular chapel with gothic style windows, aisles and a steeply pitched roof.

Following the closure of the Female Factory in January 1855 the site was handed over to the Police Department. The chapel was rented by the Catholic church for a short period as a place of worship. When questioned in parliament about this arrangement, the Colonial Secretary responded:

“Roman Catholics applied for [the] temporary use of the chapel, which was granted to them at a peppercorn rent, a written document being given to engage for its being surrendered to the Government on demand.”

It is not known when this arrangement ended but it probably existed for about two or three years. In 1862 a boys’ reformatory was proposed for the site but this came to nothing. The site was then used for various purposes before it was sold and once building material was removed it quickly became ruinous.

The site is open to the public and although little remains of the buildings, excellent historical signage and a detailed model of the Female Factory make it well worth a visit. While little is known about Female Factory chapel, it was nevertheless a critical part of of the convict and probation system and it cannot be overlooked as an element of Tasmania’s diverse ecclesiastical history.

Ross is home to one of four female factories in Tasmania, through which approximately 12,000 female convicts were ‘processed’. Ross was established in 1821 as a garrison town and a staging post on the route between Launceston and Hobart. It was also a base for Public Works Parties whose labour produced a number of local buildings and structures such as the famous Ross ‘convict bridge’. A probation station for male convicts was established at the site in 1846 and soon after this it was redeveloped as the Ross Female Factory.

In the 1840’s, landholders in the midlands agitated for the establishment of a female factory closer than the factory situated at Hobart as a source for female servants. The female factory was part of a probation system which was designed to reform the 'inequalities' and problems caused by ‘randomly’ assigning convicts to private settlers. The intention was to promote the passage of women from convict to reputable citizen. In the factories the lives of women were regulated by authority, work, surveillance, religion and finally classification into ‘classes’. After serving six months in the ‘crime class’, approved prisoners, the so-called 'hiring class', became pass holders and could work for wages outside the factory and were able to be acquired by local landowners as servants, or sometimes as wives.

The design and layout of the Ross Female Factory was shaped by its previous use as site for accomodating Public Works Parties and a male probation station. Part of the design of the complex was a chapel which was originally proposed to be located adjacent to the entrance to the station. However, It was relocated to the rear of the site, apparently on the recommendation of Superintendent E.S. Hall (a prominent Catholic) supposedly to facilitate its use by the local Catholic community. It was built on an elevated platform above the surrounding yard. Women were released from their cells and wards to attend services in this building. The drawing on the 1851 plans (see below), reveal that the building resembled a regular chapel with gothic style windows, aisles and a steeply pitched roof.

Following the closure of the Female Factory in January 1855 the site was handed over to the Police Department. The chapel was rented by the Catholic church for a short period as a place of worship. When questioned in parliament about this arrangement, the Colonial Secretary responded:

“Roman Catholics applied for [the] temporary use of the chapel, which was granted to them at a peppercorn rent, a written document being given to engage for its being surrendered to the Government on demand.”

It is not known when this arrangement ended but it probably existed for about two or three years. In 1862 a boys’ reformatory was proposed for the site but this came to nothing. The site was then used for various purposes before it was sold and once building material was removed it quickly became ruinous.

The site is open to the public and although little remains of the buildings, excellent historical signage and a detailed model of the Female Factory make it well worth a visit. While little is known about Female Factory chapel, it was nevertheless a critical part of of the convict and probation system and it cannot be overlooked as an element of Tasmania’s diverse ecclesiastical history.

|

| A detail from plans for the Ross Female Factory showing the design of the chapel. Source: Archives of Tasmania AOT PWD 266/1696 Plan of Alterations, Ross Factory 1851 |

|

| The Ross convict Chapel - a detail of a model of the site in the interpretation centre. |

Sources:

https://www.femaleconvicts.org.au/convict-institutions/female-factories/ross-ff

https://www.parks.tas.gov.au/index.aspx?base=2770. (Ross Female Factory)

http://www.taswoolcentre.com.au/museum/objects/ross-female-factory

http://www.utas.edu.au/library/companion_to_tasmanian_history/F/Female%20factories.htm

Launceston Examiner, Wednesday 10 December 1851, page 6

The Tasmanian Daily News, Wednesday 4 November 1857, page 2 (Parliament of Tasmania)

The Examiner, 25 March 1917, 'Ross female factory a reminder of darker days' article by Piia Wirsu

Interpretation signage at the Ross Female Factory site.

Ross Female Factory Station Historic Site - Conservation Plan - Parks and Wildlife Service, April 1988.

Casella, Eleanor Conlin, Archaeology of the Ross Female Factory : female incarceration in Van Diemen's Land, Australia; Queen Victoria Museum Launceston, 2002.

Australia. Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts. Australian convict sites : world heritage nomination / Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts Dept. of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts Canberra 2008 <http://www.environment.gov.au/heritage/publications/about/pubs/convict-sites.pdf>

Comments

Post a Comment