No. 443 - The Salvation Army at Scottsdale - "Simply a Religious Persecution on the Part of a Few"

The Salvation Army arrived at Scottsdale in the late 1880’s shortly after it had established bases in Launceston and Hobart. The reception to the ‘Army’ in Tasmania was initially hostile and sometimes even violent. Negative reactions to the Salvation Army were a response to the raucous nature of the ‘Army’s’ gatherings; middle class prejudice towards the working classes who were attracted to its meetings and because of its disruptive recruiting strategies which included street processions and open-air meetings. In Launceston and Hobart it was shadowed by a ‘skeleton army’ that parodied its marches and disturbed its meetings, sometimes violently. In Hobart the leader of the ‘Army’, Captain Gallagher, as well as others, were imprisoned for breaching municipal by-laws but were released after the intervention of the Attorney General.

The Salvation Army’s appearance at Scottsdale (then known as Ellesmere) in 1887 was met with mixed feelings as was voiced by the local correspondent for Launceston’s Daily Telegraph:

“I notice by a number of bright coloured posters that a contingent of the Salvation Army is to open fire in the Mechanics’ tomorrow night and five following nights. Their visit no doubt will create a good deal of excitement and small talk amongst a certain class of our religious friends….”

In September 1887 a report in the Tasmanian reveals that the ‘Army’ generally had a positive start:

“The Salvation Army has been doing wonders here during the past two weeks. “Staff Captain” Crouch has been amongst us, giving us music on his cornet, which seemed to draw large audiences, both outside and at their indoor meetings. The number of converts they have in their ranks is a sign that the peculiar method they have of propounding the Scriptures has a fascination for a certain class of individuals. They have upwards of 100 followers now, and are gaining strength every week”.

However, some of Scottsdale residents were wary of the ‘Army’ and sought to curb its activities as had been the pattern in other towns. The disruptive tactics of the ‘Army’ and the disorder that invariably ensued was a cause of concern and any untoward incident could be used as a means to restrict the noisy street processions and crowds which they attracted. At Scottsdale it was the death of a horse which provided the catalyst to attempt to clamp down on the ‘Army’. In March 1888 the local correspondent for the Launceston Examiner reported:

“The big drum has arrived to the order of the Salvation Army contingent stationed here, but its use in the streets on Sunday is very questionable taste. I feel confident that if the local band were to turn out and play on Sundays they would soon be stopped, and why should the other one be allowed to disturb the quiet of a Sunday?”

In late addendum to the report, the correspondent added that his forewarning had been vindicated:

"On Friday evening,… as the Salvation Army corps were doing the grand march past, a horse which was being led out of Harvey's place took fright at the crowd and its surroundings firing what is called a volley, and after trying its best to get away it fell against a plough, the handles of which entered behind its right shoulder. After suffering great pain it died. This is likely to occupy the attention of the court shortly. I believe our Town Board intend passing a by-law to put a stop to processions being accompanied by flags, torches, and shouting, so as to prevent accidents in the future".

The incident was indeed the subject of Police Court proceedings in the following month. The record of witnesses reveal mixed attitudes towards the ‘Army’ and that some in authority had already seized upon the incident to attempt outlaw the ‘Army’s’ street processions. The Court proceedings were reported by the Hobart Mercury as the case was of interest across Tasmania where the activities of the ‘Army’ were considered a threat to law and order as well as the interests of the establishment. The Mercury’s report on the case contains considerable detail albeit in telegraphic style. Leslie Amos, owner of horse, described the accident:

“Leslie Amos, wheelwright, deposed to having been in the act of leading a mare out of Harvey’s yard on the evening of March 23, on to the road. Was leading her by bridle, the Salvation Army was passing at the time. The mare got frightened, and staked herself by running against a plough handle, and then broke away. Was not thrown down nor fell down. The mare swung him round on to the “tire bender,” and he was slightly injured by a wound on the knee. The mare was frightened by the torches and drum of the “Army”. They were singing in rather a high tone of voice. The mare was usually quiet, except in harness. The noise produced by the “Army” was calculated to frighten horses that are timid. The mare died a few hours afterwards. Had she gone in among the people it is probable they might have been injured”.

Many witnesses supported the ‘Army’ and stated that the procession was not overly loud :

“Percy Tucker, farmer, remembered a horse being injured, belonged to Mr. Amos, one evening…, on the premises of Mr. Harvey. The “Army” were walking past in procession at the time; Hopkins was leading and had a concertina in his hand, Gould was giving out a hymn, Appleby playing a drum. There were lighted torches, a woman carrying a banner, and two or three more playing tambourines. Their singing was a little quieter than usual. Heard Hopkins say “fire a volley altogether.” It was said in a quiet tone. The drum and tambourines were struck and most of the processionists shouted “amen”, in as loud a tone as could comfortably be made…”

In his statement Gould made a strong case for the rights of the ‘Army’:

“Mr. Gould, on behalf of himself and other defendants, made an intelligent and forcible statement, referring to the usefulness of the Salvation Army in many parts of the world, and particularly, in the colonies, where they were recognised by judges, magistrates, statesmen, and Bishops and other ministers of religion us being the means of effecting vast amount of good by the promotion of the moral and spiritual welfare of a very large class of neglected people, and the diminution of crime and misery as a consequence. Their only object was to continue on the same lines, and in this district it was well known their efforts had been greatly blessed in rescuing many from lives of sin and misery. He contended that the present prosecution was simply a religious persecution on the part of a few, and an infringement on their rights and liberties as law-abiding citizens”.

In contrast, other witnesses were clearly antagonistic to the ‘Army’:

“John Spreadborough, chemist, deposed to hearing a noise in the street on the evening of 23rd March. Saw the Salvation Army walking down the street, Hopkins playing concertina as usual. Saw Appleby, but not Clark or Gould. Appleby beating the drum at intervals. Heard a voice say, “Give a volley,” and the word “amen” was shouted as loud as they could. Speaking for himself he was disturbed by the shouting and drum. Torches were carried. In his opinion the proceedings were calculated to frighten horses….”

The questioning of Thomas Heazlewood’s and the town’s superintendent of police are most revealing about the forces at work:

“Mr. Gould then called Thos. D. Heazlewood, who deposed to being a member of the Ellesmere Town Board. That no complaints had been brought before him with respect to any proceedings of the Salvation Army, and he did not think their proceedings were calculated to create a disturbance".

"To superintendent of police: Was present at a meeting of the Town Board when a motion was made that all processions should be prohibited from parading the streets of the town of Ellesmere. A by-law was passed to that effect and forwarded to the Attorney-General. He inferred that it was in consequence of what took place in connection with the Salvation Army on 23rd March that this by-law was passed".

The case was dismissed and the Army was able to continue its recruitment and proceeded to establish a permanent base in the town.

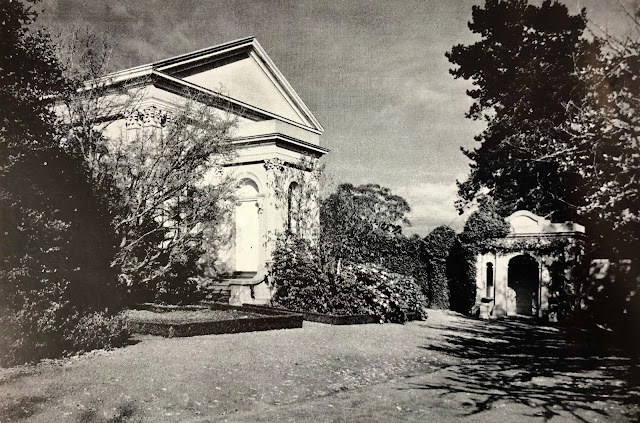

In July 1888 a block of land on Victoria Street was purchased on Victoria Street to build a barracks. Building began in September and was completed for an official opening on the 19th of November. The barracks which stood on a quarter of an acre, was a sizeable building measuring 48 x 26 feet. It was lighted by nine windows was able to seat 230.

Despite progress with the barracks the Army continued to suffer constant harassment by ‘larrikins’ and some of its own supporters contributed to the mayhem. In July 1888 the Scottsdale correspondent for The Tasmanian complained:

“A certain section of the Salvation Army followers of the larrikin type amused themselves last Sunday afternoon on returning from service by knocking at people's doors, and running away, laughing boisterously at their achievement. I am sure they are not carrying out the teaching of their captain by these ongoings, and if repeated I will certainly hand their names over, to the proper authority, for dealing with such matters….”

In November 1888, the ‘Army’ literally suffered another blow. Months early The Tasmanian had conceded:

The “lassie” with the cornet was Sarah Richardson. She became the victim of a stone throwing incident instigated by the ‘larrikin element’. The correspondent for the Hobart Mercury described the scene:

“As the Salvation Army…were making their way through the main street of Ellesmere to their usual place of meeting…. two stones were hurled from the back precincts of tenements on one side of the street, into their ranks, when quite a young member of the Army was struck on the head, and knocked down senseless, in which condition she was carried to her home near by, when it was thought that her brain had been seriously injured. She is however improving under tender care…”

The culprits were tracked down and brought before the Ellesmere Police Court on 16 November. It was one of several cases involving the Army that day:

“Daniel Thorn and Edward Williams, were charged by Superintendent Normoyle with throwing a missile, to wit, a piece of brick, at the Salvation Army, the said piece of brick striking one Sarah Richardson, causing her serious injury. After a lengthy hearing of three and a half hours, during which six witnesses were examined on behalf on the prosecution… it was decided to dismiss the case”.

In the same report carried by the Launceston Examiner it went on to describe the case of:

“an assault arising out of some boyish dispute at one of the Army meetings”.

The Examiner’s report concluded with yet another incident, this time involving a young Salvation Army member. While the activities of the ‘Army’ drew the attention of the town’s larrikins, it is also true that it attracted others, often on the fringes of society: the poor; the marginalised and the vulnerable:

“On Thursday an unfortunate young man about 18 years of age was taken in charge by the police and locked up as being of unsound mind. He was a member of the Salvation Army, and being of an excitable nature it turned his head. It was lamentable to hear his cries. When taken in charge he was running about in the middle of the night quite nude. He has been sent to New Norfolk for treatment”.

After the Sarah Richardson incident, disruption of street processions seem to have diminished but other forms of intimidation and violence continued to be problematic. In March 1889 the Examiner reported:

“A few evenings ago the Salvation Army held a harvest meeting in their barracks, and by all accounts it was anything but what it should have been. Many were trying to hit others with broken pieces of pumpkin, etc., was not in keeping with the character of the building, and it was a difficult matter to keep some from fighting”.

Throughout the 1890’s and beyond, newspaper reports and Police Court records detail dozens of incidents in the relentless efforts of the ‘larrikin element’ to undermine the ‘Army’. For example, in January 1891 the Daily Telegraph reported:

“William Clark, of Scottsdale was charged by Superintendent Beresford with having damaged nine panes of glass in the windows of the Salvation Army Barracks at Scottsdale on the night of 31st December 1890. The accused pleaded guilt and was ordered to pay £2 5s 6d, including fine, costs, and value of damage done”.

When the Scottsdale ‘Army’ visited outlying areas such as Springfield they were pelted with eggs that “were not too fresh” and “Jetsonsville larrikins” were summoned before the court for “disturbing the Salvation Army meeting at that place”.

With the passing of time, reports of disruptions gradually diminish and cease by the time of the Great War. While violence and intimidation against the religious are outrageous by today’s standards, the Salvation Army’s Scottsdale experience was no different or worse than that suffered by the ‘Army’ in most Tasmanian Town’s in the 1880’s and 1890’s.

In 1937 at the Salvation Army’s 50th anniversary at Scottsdale, some of the horrors of the pioneering salvationist was recalled but it was their achievements that were most fondly remembered:

“Granny Clarke, a coloured lady [sic] was an outstanding trophy. She joined with the Army, carried the flag for many years, lived a truely reformed life and was respected by all”.

The Salvation Army remains a part of Scottsdale’s religious landscape. The old barracks on Victoria Street are gone and have been replaced by a modern brick building situated on Arthur Street which completely belies the turbulent times of the ‘Army’s’ early years in Ellesmere.

The Salvation Army’s appearance at Scottsdale (then known as Ellesmere) in 1887 was met with mixed feelings as was voiced by the local correspondent for Launceston’s Daily Telegraph:

“I notice by a number of bright coloured posters that a contingent of the Salvation Army is to open fire in the Mechanics’ tomorrow night and five following nights. Their visit no doubt will create a good deal of excitement and small talk amongst a certain class of our religious friends….”

In September 1887 a report in the Tasmanian reveals that the ‘Army’ generally had a positive start:

“The Salvation Army has been doing wonders here during the past two weeks. “Staff Captain” Crouch has been amongst us, giving us music on his cornet, which seemed to draw large audiences, both outside and at their indoor meetings. The number of converts they have in their ranks is a sign that the peculiar method they have of propounding the Scriptures has a fascination for a certain class of individuals. They have upwards of 100 followers now, and are gaining strength every week”.

However, some of Scottsdale residents were wary of the ‘Army’ and sought to curb its activities as had been the pattern in other towns. The disruptive tactics of the ‘Army’ and the disorder that invariably ensued was a cause of concern and any untoward incident could be used as a means to restrict the noisy street processions and crowds which they attracted. At Scottsdale it was the death of a horse which provided the catalyst to attempt to clamp down on the ‘Army’. In March 1888 the local correspondent for the Launceston Examiner reported:

“The big drum has arrived to the order of the Salvation Army contingent stationed here, but its use in the streets on Sunday is very questionable taste. I feel confident that if the local band were to turn out and play on Sundays they would soon be stopped, and why should the other one be allowed to disturb the quiet of a Sunday?”

In late addendum to the report, the correspondent added that his forewarning had been vindicated:

"On Friday evening,… as the Salvation Army corps were doing the grand march past, a horse which was being led out of Harvey's place took fright at the crowd and its surroundings firing what is called a volley, and after trying its best to get away it fell against a plough, the handles of which entered behind its right shoulder. After suffering great pain it died. This is likely to occupy the attention of the court shortly. I believe our Town Board intend passing a by-law to put a stop to processions being accompanied by flags, torches, and shouting, so as to prevent accidents in the future".

The incident was indeed the subject of Police Court proceedings in the following month. The record of witnesses reveal mixed attitudes towards the ‘Army’ and that some in authority had already seized upon the incident to attempt outlaw the ‘Army’s’ street processions. The Court proceedings were reported by the Hobart Mercury as the case was of interest across Tasmania where the activities of the ‘Army’ were considered a threat to law and order as well as the interests of the establishment. The Mercury’s report on the case contains considerable detail albeit in telegraphic style. Leslie Amos, owner of horse, described the accident:

“Leslie Amos, wheelwright, deposed to having been in the act of leading a mare out of Harvey’s yard on the evening of March 23, on to the road. Was leading her by bridle, the Salvation Army was passing at the time. The mare got frightened, and staked herself by running against a plough handle, and then broke away. Was not thrown down nor fell down. The mare swung him round on to the “tire bender,” and he was slightly injured by a wound on the knee. The mare was frightened by the torches and drum of the “Army”. They were singing in rather a high tone of voice. The mare was usually quiet, except in harness. The noise produced by the “Army” was calculated to frighten horses that are timid. The mare died a few hours afterwards. Had she gone in among the people it is probable they might have been injured”.

Many witnesses supported the ‘Army’ and stated that the procession was not overly loud :

“Percy Tucker, farmer, remembered a horse being injured, belonged to Mr. Amos, one evening…, on the premises of Mr. Harvey. The “Army” were walking past in procession at the time; Hopkins was leading and had a concertina in his hand, Gould was giving out a hymn, Appleby playing a drum. There were lighted torches, a woman carrying a banner, and two or three more playing tambourines. Their singing was a little quieter than usual. Heard Hopkins say “fire a volley altogether.” It was said in a quiet tone. The drum and tambourines were struck and most of the processionists shouted “amen”, in as loud a tone as could comfortably be made…”

In his statement Gould made a strong case for the rights of the ‘Army’:

“Mr. Gould, on behalf of himself and other defendants, made an intelligent and forcible statement, referring to the usefulness of the Salvation Army in many parts of the world, and particularly, in the colonies, where they were recognised by judges, magistrates, statesmen, and Bishops and other ministers of religion us being the means of effecting vast amount of good by the promotion of the moral and spiritual welfare of a very large class of neglected people, and the diminution of crime and misery as a consequence. Their only object was to continue on the same lines, and in this district it was well known their efforts had been greatly blessed in rescuing many from lives of sin and misery. He contended that the present prosecution was simply a religious persecution on the part of a few, and an infringement on their rights and liberties as law-abiding citizens”.

In contrast, other witnesses were clearly antagonistic to the ‘Army’:

“John Spreadborough, chemist, deposed to hearing a noise in the street on the evening of 23rd March. Saw the Salvation Army walking down the street, Hopkins playing concertina as usual. Saw Appleby, but not Clark or Gould. Appleby beating the drum at intervals. Heard a voice say, “Give a volley,” and the word “amen” was shouted as loud as they could. Speaking for himself he was disturbed by the shouting and drum. Torches were carried. In his opinion the proceedings were calculated to frighten horses….”

The questioning of Thomas Heazlewood’s and the town’s superintendent of police are most revealing about the forces at work:

“Mr. Gould then called Thos. D. Heazlewood, who deposed to being a member of the Ellesmere Town Board. That no complaints had been brought before him with respect to any proceedings of the Salvation Army, and he did not think their proceedings were calculated to create a disturbance".

"To superintendent of police: Was present at a meeting of the Town Board when a motion was made that all processions should be prohibited from parading the streets of the town of Ellesmere. A by-law was passed to that effect and forwarded to the Attorney-General. He inferred that it was in consequence of what took place in connection with the Salvation Army on 23rd March that this by-law was passed".

"To Bench: Two out of the five members of the Town Board objected to the passing of the by-law referred to. T. Tucker, late storekeeper and postmaster of Ellesmere, deposed that in his opinion he did not think the processions of the Salvation Army were calculated to disturb the peace, but were calculated to promote the moral welfare of the people; that he resided close to the hall where their meetings were held, and had nothing to complain of in connection with their proceedings”.

The case was dismissed and the Army was able to continue its recruitment and proceeded to establish a permanent base in the town.

In July 1888 a block of land on Victoria Street was purchased on Victoria Street to build a barracks. Building began in September and was completed for an official opening on the 19th of November. The barracks which stood on a quarter of an acre, was a sizeable building measuring 48 x 26 feet. It was lighted by nine windows was able to seat 230.

Despite progress with the barracks the Army continued to suffer constant harassment by ‘larrikins’ and some of its own supporters contributed to the mayhem. In July 1888 the Scottsdale correspondent for The Tasmanian complained:

“A certain section of the Salvation Army followers of the larrikin type amused themselves last Sunday afternoon on returning from service by knocking at people's doors, and running away, laughing boisterously at their achievement. I am sure they are not carrying out the teaching of their captain by these ongoings, and if repeated I will certainly hand their names over, to the proper authority, for dealing with such matters….”

In November 1888, the ‘Army’ literally suffered another blow. Months early The Tasmanian had conceded:

“The band has improved very much of late, and has among its members a phenomenon in the shape of a lassie cornet player, who marches along, inflating her cheeks, doing her best to bring out the sweet tones of the instrument…”.

The “lassie” with the cornet was Sarah Richardson. She became the victim of a stone throwing incident instigated by the ‘larrikin element’. The correspondent for the Hobart Mercury described the scene:

“As the Salvation Army…were making their way through the main street of Ellesmere to their usual place of meeting…. two stones were hurled from the back precincts of tenements on one side of the street, into their ranks, when quite a young member of the Army was struck on the head, and knocked down senseless, in which condition she was carried to her home near by, when it was thought that her brain had been seriously injured. She is however improving under tender care…”

The culprits were tracked down and brought before the Ellesmere Police Court on 16 November. It was one of several cases involving the Army that day:

“Daniel Thorn and Edward Williams, were charged by Superintendent Normoyle with throwing a missile, to wit, a piece of brick, at the Salvation Army, the said piece of brick striking one Sarah Richardson, causing her serious injury. After a lengthy hearing of three and a half hours, during which six witnesses were examined on behalf on the prosecution… it was decided to dismiss the case”.

In the same report carried by the Launceston Examiner it went on to describe the case of:

“an assault arising out of some boyish dispute at one of the Army meetings”.

The Examiner’s report concluded with yet another incident, this time involving a young Salvation Army member. While the activities of the ‘Army’ drew the attention of the town’s larrikins, it is also true that it attracted others, often on the fringes of society: the poor; the marginalised and the vulnerable:

“On Thursday an unfortunate young man about 18 years of age was taken in charge by the police and locked up as being of unsound mind. He was a member of the Salvation Army, and being of an excitable nature it turned his head. It was lamentable to hear his cries. When taken in charge he was running about in the middle of the night quite nude. He has been sent to New Norfolk for treatment”.

After the Sarah Richardson incident, disruption of street processions seem to have diminished but other forms of intimidation and violence continued to be problematic. In March 1889 the Examiner reported:

“A few evenings ago the Salvation Army held a harvest meeting in their barracks, and by all accounts it was anything but what it should have been. Many were trying to hit others with broken pieces of pumpkin, etc., was not in keeping with the character of the building, and it was a difficult matter to keep some from fighting”.

Throughout the 1890’s and beyond, newspaper reports and Police Court records detail dozens of incidents in the relentless efforts of the ‘larrikin element’ to undermine the ‘Army’. For example, in January 1891 the Daily Telegraph reported:

“William Clark, of Scottsdale was charged by Superintendent Beresford with having damaged nine panes of glass in the windows of the Salvation Army Barracks at Scottsdale on the night of 31st December 1890. The accused pleaded guilt and was ordered to pay £2 5s 6d, including fine, costs, and value of damage done”.

When the Scottsdale ‘Army’ visited outlying areas such as Springfield they were pelted with eggs that “were not too fresh” and “Jetsonsville larrikins” were summoned before the court for “disturbing the Salvation Army meeting at that place”.

With the passing of time, reports of disruptions gradually diminish and cease by the time of the Great War. While violence and intimidation against the religious are outrageous by today’s standards, the Salvation Army’s Scottsdale experience was no different or worse than that suffered by the ‘Army’ in most Tasmanian Town’s in the 1880’s and 1890’s.

In 1937 at the Salvation Army’s 50th anniversary at Scottsdale, some of the horrors of the pioneering salvationist was recalled but it was their achievements that were most fondly remembered:

“Granny Clarke, a coloured lady [sic] was an outstanding trophy. She joined with the Army, carried the flag for many years, lived a truely reformed life and was respected by all”.

The Salvation Army remains a part of Scottsdale’s religious landscape. The old barracks on Victoria Street are gone and have been replaced by a modern brick building situated on Arthur Street which completely belies the turbulent times of the ‘Army’s’ early years in Ellesmere.

|

| The old Scottsdale 'barracks' in Victoria Street: Source: Tasmanian Mail 1906 |

|

| Photograph: Duncan Grant 2019 |

|

| Photograph: Duncan Grant 2019 |

|

| Photograph: Duncan Grant 2019 |

Sources:

Daily Telegraph, Thursday 16 June 1887, page 3

The Tasmanian, Saturday 10 September 1887, page 13

Daily Telegraph, Thursday 8 September 1887, page 3

Launceston Examiner, Saturday 5 November 1887, page 1

Launceston Examiner, Saturday 31 March 1888, page 1

Launceston Examiner, Thursday 5 April 1888, page 4

Mercury, Wednesday 25 April 1888, page 4

The Tasmanian, Saturday 28 April 1888, page 25

The Tasmanian, Saturday 14 July 1888, page 7

The Tasmanian, Saturday 28 July 1888, page 26

Daily Telegraph, Monday 13 August 1888, page 3

Daily Telegraph, Saturday 15 September 1888, page 2

The Mercury, Monday 12 November 1888, page 4

Daily Telegraph, Tuesday 20 November 1888, page 3

The Mercury, Tuesday 20 November 1888, page 2

Launceston Examiner, Friday 23 November 1888, page 3

The Tasmanian, Saturday 24 November 1888, page 26

The Tasmanian, Saturday 15 December 1888, page 12

Launceston Examiner, Thursday 28 March 1889, page 3

The Daily Telegraph, Saturday 17 January 1891, page 6

The Mercury, Saturday 13 May 1891, page 2

The Tasmanian Mail, 29 December 1906, page 17 (insert)

North-Eastern Advertiser, Friday 2 July 1937, page 3

Comments

Post a Comment