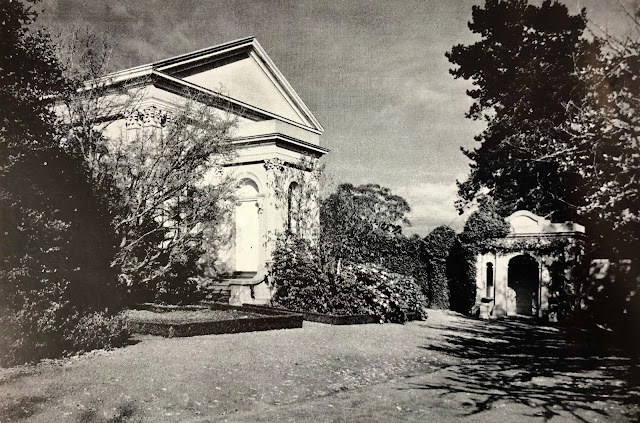

No. 530 - The Chapel at Oatlands Gaol

The brutality of the convict system in colonial Tasmania is rightly a central theme in popular history. However, a critical point is that for all of the system’s notorious cruelty, it was in fact (at least in theory) a revolutionary system designed to reform the criminal class. As such, religion was an integral part of the penal system in Tasmania and played a critical role in the reform of the convict population. A report from 2008 which advocated World Heritage listing of Australia’s convict sites notes that this was achieved through:

“…The construction of churches and chapels for the use of convicts; employment of chaplains at penal stations responsible for the moral improvement of convicts; compulsory attendance at church services; reading of prayers by authorities and ‘private masters’ and distribution of Bibles. Separate churches or rooms were often provided for convicts from different religious denominations. Religious observances were often an essential part of the daily lives of most convicts including those under going secondary punishment. Attendance was rigidly enforced and non-attendance was a punishable offence. Under the probation system, convicts were required to commence and end each day with prayers and attend two divine services on Sundays. Clergymen were critical cogs in the penal machinery, expected to be knowledgeable about the character of each convict. They were required to sign all key documents that could lead to the rehabilitation and freedom of individual convicts including applications for family members to be sent from Britain, tickets-of-leave, special privileges and pardons”.

The Oatlands Gaol (1836) was the largest regional gaol in colonial Tasmania being built to hold up to 200 prisoners. By 1849 Oatlands was the only remaining fully functional rural gaol in the colony. Despite public opposition, most of the gaol was demolished in 1937. The most significant remnant of the gaol complex is the arched entranceway, which was removed before being returned to its original position in 2015.

The Oatlands Gaol chapel was located on the second floor in a wooden structure built above 6 cells. Like most prison chapels, very little information is available about its appearance or contents as this was an aspect of prison life of little interest. While searching newspaper records I came across a fleeting reference to the chapel in a two-part article published in the Examiner in 1893. I have reproduced the entire article written by “The Scout”. It is a whimsical but nevertheless interesting and detailed description of the gaol which was already in an advanced state of decay by the 1890’s.

The Examiner 28 January 1893 (Part 1) and 11 February 1893 (Part 2)

Auld Lang Syne Papers (By the Scout) - No. 6 and No. 7 - Stone Walls

A.D. 1834 was the year the Oatlands gaol was finished in. This massive square shaped structure impresses the onlooker of today with an idea of its having seen better; or, shall I say, darker days. Perhaps, all things considered, the latter phrase would be the more correct. The area of ground covered by this gruesome looking relic of the past is considerable, and numerous contingents of prisoners were accommodated within its walls in the earlier days of the colony. Oatlands was in those times an important centre, the Supreme Court was held there, and a detachment of military aided the constabulary in maintaining law and order.

Despite its dimensions the prison, over looking the dingy-coloured surface of Lake Dulverton, was none too large, for the demands made upon its space were occasionally pretty extensive. However the day arrived eventually when the claims of the free colonist were listened to; when the word "penal" in its worst significance could be used no more so far as the land they had adopted as their home was concerned. Since that date Oatlands gaol, like many of its fellow structures in different parts of the island, has fallen into the position of an institution which, having served its purpose, is left to the mercy of time and the hour to effect a gradual but certain decay. It still remains in use to a very limited extent as a house of detention for the district "drunk and incapable," or for that irrepressible class of individual whose peculiar characteristics may be summed up under the short but comprehensive heading "no visible means of support."

Some few weeks ago I was afforded an opportunity of wandering through the building and noting the condition the lapse of years has left it in. The huge black wooden gates through which I entered hung precariously upon the scantiest of support, the hinges having for the most part fallen a prey to rust. From the entrance I was conducted by the janitor to the old condemned cells, now doing duty as the Oatlands lock up. These apartments are of the regulation size, and are not, by any means, very cheerful-looking places wherein to pass a spare half hour. The passage between the cells and neighbouring wall is barred across overhead, but despite this precaution, tradition hath it a prisoner “once upon a time" squeezed himself through, only to find there was no chance whatever of his escaping after having undergone a perfect purgatory of suffering in accomplishing the feat. One of the powerful looking bars has been bent, and upon asking the reason, I was informed that Donald Dinnie, the well-known athlete, whilst visiting the gaol during the course of his tour in Tasmania, in a playful moment tested which was the stronger he or the bar. The Scottish Sampson evidently had it all his own way during the preliminary tussle, but the bar ultimately had the advantage in regard to staying power.

Years ago public executions frequently took place at Oatlands. The scaffold was erected over the main entrance, the marks in the stone where the structure was fixed still being visible. The fixture was placed so that the head and shoulders of the condemned were visible to the crowd outside. The last execution in Oatlands gaol is reported as having taken place somewhere about 1860, when “Long Mick" paid the last penalty to justice for the murder of Mr Sturgeon. The scaffold was subsequently removed to a courtyard in close proximity to the condemned cells, where it remained until some fifteen months since, when it was taken down.

There is an old-time rumour afloat in the neighbourhood to this day that a prisoner awaiting execution in the Oatlands gaol could look out between the bars of his cell-window at the work men fixing up the gallows upon which he was so soon to render up his life. The same story has to my certain knowledge been told in connection with many other gaols throughout the colonies. So far as Oatlands is concerned there could never have been any possibility of such a circumstance taking place. The tale, however, is one that "goes well” in the telling, and this being the case it is certain to die hard.

Quitting the spot where the scaffold so lately stood I was taken to the old Government well, a substantial structure of considerable depth. It is said that a couple of prisoners contrived to get down this dark and cooling hole "once upon a time." Why they did get down there I do not know, but from all appearances they could not have had a very rollicking time of it when they had accomplished their purpose. From the well we proceeded to the main cells. Each of these apartments is 3ft 6in across, 8ft 6in in length, and 9ft high.

Ascending a some what circuitous staircase we reached what was once the gaol chapel, where prisoners were wont, in the days that are past, to assemble to worship under strict supervision. By-the-way, speaking of these stairs the janitor informed me that a cow had walked leisurely up them not long before, and was found making a careful inspection of the upper storey. The cow belonged to the janitor, and from babyhood, I understand, possessed a peculiarly enquiring turn of mind.

From the chapel we marched through a long passage, with cells on one side, and a wall with windows looking out upon the courtyard on the other. At the extremity of this passage I found myself passing into an apartment, the counterpart of the chapel, but what it was originally used for history recordeth not. I noted that the fireplace had been bricked up, and on enquiring the reason was told that in years gone by female convicts were imprisoned in the adjoining part of the building. Some of the males on the other side, knowing that only the comparatively thin wall at the rear of the fireplace kept them from joining the ladies, knocked down the obstruction. They did not profit much, however, by the venture, for speedy detection followed, and a term in irons was the reward of their exertions.

From there the janitor, conducted me down stairs once more, through the exercise yard, and into a portion of the building which it is supposed was utilised as female quarters. "If you care to mount that ladder," he remarked to me, “I will show you some specimens of the leg-irons prisoners were often compelled to wear in the early day.” The task of climbing that ladder was by no means, an inviting one. The stairway to the upper floor of the prison had disappeared, and the substitute was a decidedly shaky looking construction altogether. A weather-beaten half-rotten platform jutted out from the upper storey, some 20ft from the ground, and against this the ladder rested. I weigh exactly l4st., and felt somewhat dubious concerning the staying powers of both ladder and platform. However, I was there for the purpose of seeing all that was to be seen, so up I must go, or perish in the attempt. The janitor assured me it was “all right”, and as I fancied. I could trace in his countenance a dim, indistinct likeness to a portrait I once saw of George Washington, I felt that the man simply spoke what he felt. I accordingly placed implicit faith in his integrity and requested him to go first. He obeyed instructions. When I saw him firmly planted on the platform I felt convinced; I did the correct thing in trusting him. So planting my foot on the bottom rung of the ladder I contrived, after sundry gymnastics, to reach the threshold of the somewhat mysterious chamber wherein the leg-irons, together with a quantity of other prison paraphernalia, were discovered stowed away not so very long ago. “That was a steadier for a man to carry around with him,” remarked the janitor, as he lifted one of the heaviest irons from the floor. I tried its weight, and agreed it certainly was a big handicap for a human being to be penalised with. How any unfortunate creature could possibly get about under such a distressing weight it is hard indeed to imagine.

However, from all accounts many did so get about, but the majority carried the effects of the punishment to their graves. “That box in the corner, “remarked the janitor, “is full of prison clothing as good as new.” I examined the box, and found its, contents comprised a number of suits of the well known dark grey, the material being evidently as sound as the day it was made up. There were also a number of the regulation boots, none of which had ever seen service. Rather formidable looking things these gaol boots, rejoicing in all the glory of thick soles, and nails large enough to gladden the heart of the most fastidious navvy. Tossed out upon the floor were dozens of glazed leather caps, in shape something after the style of a bishop's mitre. In various parts of of the room I came across piles of shirts, old lamps, gaol candlesticks, rivets for fixing on leg irons, and last of all a sadly neglected copy of the Bible. The jury box which had been used in the old Supreme Court lay covered with the dust of years in a corner amongst a quantity of rubbish of a miscellaneous character. The witness box had evidently been utilised as a fowl roost, while near at hand I picked up a couple of javelins. By-the-way, speaking of these rods of office, I might state that Cleary, the father of the good-natured janitor, to whom I have on more than one occasion referred in these notes, was a javelin man in the palmy days of Oatlands.

Having duly inspected the curiosities of the store-house I followed my conductor down the ladder, and breathed a gentle sigh of relief as my feet touched terra firma once again. Opening the door of what had formerly been a cell on the ground floor I found a sleek-looking horse enjoying his mid-day meal in the apartment. Two cells had, I noticed, been knocked into one, and a very substantial stable thus formed. I was shown some stone slabs, said to have been taken from over the cell ceilings. As they weighed somewhere about five hundredweights each I felt dubious, but that dim, indistinct likeness to the portrait I saw in days gone by of George Washington came once more to the janitor's rescue, and I believed him. After a glance at some of the heavily-constructed inside walls, now hastening to decay, I thanked my guide for the trouble he had taken in conducting me over the building and passed through the black, ominous-look ing gates of the prison house.

Oatlands gaol has still many interesting relics to interest those who profess a taste in ruins, but if the Government does not see its way clear to utilise it in some way, thus affording justification for it, being kept in repair, the huge structure will be worthless in another ten years, for the hand of time has already pressed pretty heavily upon it.. A suggestion to turn it into a place of detention for juvenile. offenders has already been brought before Parliament, and fresh representations on the same subject are, I understand, to be made during the coming session”.

“…The construction of churches and chapels for the use of convicts; employment of chaplains at penal stations responsible for the moral improvement of convicts; compulsory attendance at church services; reading of prayers by authorities and ‘private masters’ and distribution of Bibles. Separate churches or rooms were often provided for convicts from different religious denominations. Religious observances were often an essential part of the daily lives of most convicts including those under going secondary punishment. Attendance was rigidly enforced and non-attendance was a punishable offence. Under the probation system, convicts were required to commence and end each day with prayers and attend two divine services on Sundays. Clergymen were critical cogs in the penal machinery, expected to be knowledgeable about the character of each convict. They were required to sign all key documents that could lead to the rehabilitation and freedom of individual convicts including applications for family members to be sent from Britain, tickets-of-leave, special privileges and pardons”.

The Oatlands Gaol (1836) was the largest regional gaol in colonial Tasmania being built to hold up to 200 prisoners. By 1849 Oatlands was the only remaining fully functional rural gaol in the colony. Despite public opposition, most of the gaol was demolished in 1937. The most significant remnant of the gaol complex is the arched entranceway, which was removed before being returned to its original position in 2015.

The Oatlands Gaol chapel was located on the second floor in a wooden structure built above 6 cells. Like most prison chapels, very little information is available about its appearance or contents as this was an aspect of prison life of little interest. While searching newspaper records I came across a fleeting reference to the chapel in a two-part article published in the Examiner in 1893. I have reproduced the entire article written by “The Scout”. It is a whimsical but nevertheless interesting and detailed description of the gaol which was already in an advanced state of decay by the 1890’s.

The Examiner 28 January 1893 (Part 1) and 11 February 1893 (Part 2)

Auld Lang Syne Papers (By the Scout) - No. 6 and No. 7 - Stone Walls

A.D. 1834 was the year the Oatlands gaol was finished in. This massive square shaped structure impresses the onlooker of today with an idea of its having seen better; or, shall I say, darker days. Perhaps, all things considered, the latter phrase would be the more correct. The area of ground covered by this gruesome looking relic of the past is considerable, and numerous contingents of prisoners were accommodated within its walls in the earlier days of the colony. Oatlands was in those times an important centre, the Supreme Court was held there, and a detachment of military aided the constabulary in maintaining law and order.

Despite its dimensions the prison, over looking the dingy-coloured surface of Lake Dulverton, was none too large, for the demands made upon its space were occasionally pretty extensive. However the day arrived eventually when the claims of the free colonist were listened to; when the word "penal" in its worst significance could be used no more so far as the land they had adopted as their home was concerned. Since that date Oatlands gaol, like many of its fellow structures in different parts of the island, has fallen into the position of an institution which, having served its purpose, is left to the mercy of time and the hour to effect a gradual but certain decay. It still remains in use to a very limited extent as a house of detention for the district "drunk and incapable," or for that irrepressible class of individual whose peculiar characteristics may be summed up under the short but comprehensive heading "no visible means of support."

Some few weeks ago I was afforded an opportunity of wandering through the building and noting the condition the lapse of years has left it in. The huge black wooden gates through which I entered hung precariously upon the scantiest of support, the hinges having for the most part fallen a prey to rust. From the entrance I was conducted by the janitor to the old condemned cells, now doing duty as the Oatlands lock up. These apartments are of the regulation size, and are not, by any means, very cheerful-looking places wherein to pass a spare half hour. The passage between the cells and neighbouring wall is barred across overhead, but despite this precaution, tradition hath it a prisoner “once upon a time" squeezed himself through, only to find there was no chance whatever of his escaping after having undergone a perfect purgatory of suffering in accomplishing the feat. One of the powerful looking bars has been bent, and upon asking the reason, I was informed that Donald Dinnie, the well-known athlete, whilst visiting the gaol during the course of his tour in Tasmania, in a playful moment tested which was the stronger he or the bar. The Scottish Sampson evidently had it all his own way during the preliminary tussle, but the bar ultimately had the advantage in regard to staying power.

Years ago public executions frequently took place at Oatlands. The scaffold was erected over the main entrance, the marks in the stone where the structure was fixed still being visible. The fixture was placed so that the head and shoulders of the condemned were visible to the crowd outside. The last execution in Oatlands gaol is reported as having taken place somewhere about 1860, when “Long Mick" paid the last penalty to justice for the murder of Mr Sturgeon. The scaffold was subsequently removed to a courtyard in close proximity to the condemned cells, where it remained until some fifteen months since, when it was taken down.

There is an old-time rumour afloat in the neighbourhood to this day that a prisoner awaiting execution in the Oatlands gaol could look out between the bars of his cell-window at the work men fixing up the gallows upon which he was so soon to render up his life. The same story has to my certain knowledge been told in connection with many other gaols throughout the colonies. So far as Oatlands is concerned there could never have been any possibility of such a circumstance taking place. The tale, however, is one that "goes well” in the telling, and this being the case it is certain to die hard.

Quitting the spot where the scaffold so lately stood I was taken to the old Government well, a substantial structure of considerable depth. It is said that a couple of prisoners contrived to get down this dark and cooling hole "once upon a time." Why they did get down there I do not know, but from all appearances they could not have had a very rollicking time of it when they had accomplished their purpose. From the well we proceeded to the main cells. Each of these apartments is 3ft 6in across, 8ft 6in in length, and 9ft high.

Ascending a some what circuitous staircase we reached what was once the gaol chapel, where prisoners were wont, in the days that are past, to assemble to worship under strict supervision. By-the-way, speaking of these stairs the janitor informed me that a cow had walked leisurely up them not long before, and was found making a careful inspection of the upper storey. The cow belonged to the janitor, and from babyhood, I understand, possessed a peculiarly enquiring turn of mind.

From the chapel we marched through a long passage, with cells on one side, and a wall with windows looking out upon the courtyard on the other. At the extremity of this passage I found myself passing into an apartment, the counterpart of the chapel, but what it was originally used for history recordeth not. I noted that the fireplace had been bricked up, and on enquiring the reason was told that in years gone by female convicts were imprisoned in the adjoining part of the building. Some of the males on the other side, knowing that only the comparatively thin wall at the rear of the fireplace kept them from joining the ladies, knocked down the obstruction. They did not profit much, however, by the venture, for speedy detection followed, and a term in irons was the reward of their exertions.

From there the janitor, conducted me down stairs once more, through the exercise yard, and into a portion of the building which it is supposed was utilised as female quarters. "If you care to mount that ladder," he remarked to me, “I will show you some specimens of the leg-irons prisoners were often compelled to wear in the early day.” The task of climbing that ladder was by no means, an inviting one. The stairway to the upper floor of the prison had disappeared, and the substitute was a decidedly shaky looking construction altogether. A weather-beaten half-rotten platform jutted out from the upper storey, some 20ft from the ground, and against this the ladder rested. I weigh exactly l4st., and felt somewhat dubious concerning the staying powers of both ladder and platform. However, I was there for the purpose of seeing all that was to be seen, so up I must go, or perish in the attempt. The janitor assured me it was “all right”, and as I fancied. I could trace in his countenance a dim, indistinct likeness to a portrait I once saw of George Washington, I felt that the man simply spoke what he felt. I accordingly placed implicit faith in his integrity and requested him to go first. He obeyed instructions. When I saw him firmly planted on the platform I felt convinced; I did the correct thing in trusting him. So planting my foot on the bottom rung of the ladder I contrived, after sundry gymnastics, to reach the threshold of the somewhat mysterious chamber wherein the leg-irons, together with a quantity of other prison paraphernalia, were discovered stowed away not so very long ago. “That was a steadier for a man to carry around with him,” remarked the janitor, as he lifted one of the heaviest irons from the floor. I tried its weight, and agreed it certainly was a big handicap for a human being to be penalised with. How any unfortunate creature could possibly get about under such a distressing weight it is hard indeed to imagine.

However, from all accounts many did so get about, but the majority carried the effects of the punishment to their graves. “That box in the corner, “remarked the janitor, “is full of prison clothing as good as new.” I examined the box, and found its, contents comprised a number of suits of the well known dark grey, the material being evidently as sound as the day it was made up. There were also a number of the regulation boots, none of which had ever seen service. Rather formidable looking things these gaol boots, rejoicing in all the glory of thick soles, and nails large enough to gladden the heart of the most fastidious navvy. Tossed out upon the floor were dozens of glazed leather caps, in shape something after the style of a bishop's mitre. In various parts of of the room I came across piles of shirts, old lamps, gaol candlesticks, rivets for fixing on leg irons, and last of all a sadly neglected copy of the Bible. The jury box which had been used in the old Supreme Court lay covered with the dust of years in a corner amongst a quantity of rubbish of a miscellaneous character. The witness box had evidently been utilised as a fowl roost, while near at hand I picked up a couple of javelins. By-the-way, speaking of these rods of office, I might state that Cleary, the father of the good-natured janitor, to whom I have on more than one occasion referred in these notes, was a javelin man in the palmy days of Oatlands.

Having duly inspected the curiosities of the store-house I followed my conductor down the ladder, and breathed a gentle sigh of relief as my feet touched terra firma once again. Opening the door of what had formerly been a cell on the ground floor I found a sleek-looking horse enjoying his mid-day meal in the apartment. Two cells had, I noticed, been knocked into one, and a very substantial stable thus formed. I was shown some stone slabs, said to have been taken from over the cell ceilings. As they weighed somewhere about five hundredweights each I felt dubious, but that dim, indistinct likeness to the portrait I saw in days gone by of George Washington came once more to the janitor's rescue, and I believed him. After a glance at some of the heavily-constructed inside walls, now hastening to decay, I thanked my guide for the trouble he had taken in conducting me over the building and passed through the black, ominous-look ing gates of the prison house.

Oatlands gaol has still many interesting relics to interest those who profess a taste in ruins, but if the Government does not see its way clear to utilise it in some way, thus affording justification for it, being kept in repair, the huge structure will be worthless in another ten years, for the hand of time has already pressed pretty heavily upon it.. A suggestion to turn it into a place of detention for juvenile. offenders has already been brought before Parliament, and fresh representations on the same subject are, I understand, to be made during the coming session”.

| ||

| The Gaol Chapel situated above a row of cells (1926) - source: State Library of Victoria (A.C. Dreir postcard Collection |

|

| The Oatlands Gaol - Source Libraries Tasmania |

|

| A section of a plan of the Gaol showing the Chapel's location - Source Libraries Tasmania (PWD266-1-1564) |

|

| The Condemned Cell - Source: State Library of Victoria (A.C. Dreir Postcard Collection) |

Sources:

Brad Williams, Oatlands Gaol Interpretation plan, January 2011, Southern Midlands Council.

Australia. Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts. Australian convict sites : world heritage nomination / Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts Dept. of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts Canberra 2008 <http://www.environment.gov.au/heritage/publications/about/pubs/convict-sites.pdf>

Launceston Examiner, Saturday 28 January 1893, page 10

Launceston Examiner, Saturday 11 February 1893, page 7

Comments

Post a Comment