No. 545 - Burnie - St George's Anglican Church (1850-1883) - "I am not going to hawk religion about"

Burnie is a port city on the north-west coast of Tasmania. Burnie’s origins date back to 1827 when a settlement was established at Emu Bay by the Van Diemen’s Land Company. The settlement was later renamed Burnie after William Burnie, a director of the Van Diemen's Land Company.

The first official Church of England service at Emu Bay was conducted by Reverend Grigg in 1843 and was held in a large room in the Van Diemen’s Land Company’s homestead. At the time the house was occupied by the Surveyor Nathaniel Kentish. An unexpectedly large congregation numbering seventy persons attended who were accommodated with some difficulty.

In 1850 Burnie’s first Anglican church was built. In June the Hobart Courier reported:

“[A] meeting was held to call for tenders for building a Protestant place of worship, which was respectably attended, and a large sum of money subscribed for that purpose. A gentleman is expected shortly from Melbourne to take charge of the congregation, as catechist. A tender has since been accepted, and the building will be commenced Immediately”.

In October 1850 a report in The Cornwall Chronicle noted that the church was yet to be completed:

“A neat Protestant Chapel has been erected close to the “Ship Inn,” but is not yet completed. It is supposed to be able to accomodate about 200 persons when finished”.

Burnie: A Thematic History, Burnie City Council 2010 (Burnie City Heritage Survey)

Henslowe, Dorothea I and Hurburgh, Isa Our heritage of Anglican churches in Tasmania. Mercury-Walch, Moonah, Tas, 1978.

The first official Church of England service at Emu Bay was conducted by Reverend Grigg in 1843 and was held in a large room in the Van Diemen’s Land Company’s homestead. At the time the house was occupied by the Surveyor Nathaniel Kentish. An unexpectedly large congregation numbering seventy persons attended who were accommodated with some difficulty.

In 1850 Burnie’s first Anglican church was built. In June the Hobart Courier reported:

“[A] meeting was held to call for tenders for building a Protestant place of worship, which was respectably attended, and a large sum of money subscribed for that purpose. A gentleman is expected shortly from Melbourne to take charge of the congregation, as catechist. A tender has since been accepted, and the building will be commenced Immediately”.

In October 1850 a report in The Cornwall Chronicle noted that the church was yet to be completed:

“A neat Protestant Chapel has been erected close to the “Ship Inn,” but is not yet completed. It is supposed to be able to accomodate about 200 persons when finished”.

St George’s was located on “Rocky Hill” on the north side of Wilmot Street. It was built by Thomas Wiseman who was a local carpenter and shipwright. It was completed by early 1851 but only consecrated in 1855. A permanent minister, Reverend Zachary Pocock, was appointed in December 1851. This appointment resulted in 8 years of scandal and misery for the Anglicans of Emu Bay. A hint of these difficult years is summed up in the Burnie City Heritage Survey:

“The first rector to be appointed to St George’s was the Reverend Zachary Pocock. Reverend Pocock’s time at Burnie was troubled and filled with conflict. In addition to his desecration of a local cemetery, Pocock was perceived as being arrogant and provocative, even resorting to physical altercation. As a result, attendance at the Chapel fell and locals petitioned the Bishop for Pocock’s removal”.

Zachary Pocock was the son of Reverend George Pocock, one-time incumbent of St Paul’s, Marylebone, London. Zachary Pocock was a man who had many irons in the fire. In addition to being an ordained minster he was a medical doctor and also seemed to have had aspirations to practice law. The first hint of trouble came in 1855 when ‘The People’s Advocate or True Friend of Tasmania’ reported on the difficulties the Anglican congregation was having with the new Missionary Chaplain:

“Again great complaints are made respecting the Revd Mr. Pocock, who it is said thinks more of his potato crops than the souls of those the government pay him to look after. The residents at the Bay are most anxious to get up a school for the education of their children, but Mr. Pocock declines taking any active part in getting the children educated because forsooth one of the residents spoke to him rather sharply upon the subject when applied to for a subscription”.

The report continued:

“On Monday week a meeting was called of the Protestant residents of Emu Bay, for the purpose of entering into a subscription to add to the government pay of the Rev. Mr. Pocock, and the assembly consisted of the two churchwardens and the Rev. gentleman himself. When remonstrated with upon his want of zeal in collecting his flock together and mixing more with his congregation, the Rev. gentleman replied, "the Church is there, they can come if they like, but I am not going to hawk religion about." The protestants also complain of the negligence of Mr. Pocock in not getting the burying ground consecrated, notwithstanding Mr. Pocock has been resident there upwards of two years, verily the Church is in danger at Emu Bay”.

In November of the same year a parishioner, James Munce, penned a lengthly letter of complaint to the Launceston Examiner in response to Pocock’s libellous defence of allegations made against him. The accusations made by Munce are astonishing:

“….They are established facts, that the church is not attended, that the burial ground is desecrated, and that Mr. Pocock is now, and has been for some time past, engaged in secular affairs. The first part is proved by the publishled list, and which I vouch for as correct. The ploughing up part of the burial ground, and sowing grain on it, and removing the fence around it, is a fact; and if selling potatoes, fruit, butter, milk, &c., and trafficking in timber, is not engaging in secular affairs, I don't know what is. I observe his remark that "there are not twenty adult members of the Church of England residing on the township of Emu Bay"; but I submit that the souls of children ought to be be as much attended to as adults; …. Mr. Pocock asserts that during twelve years' residence in the colony his character has been unimpeached; I can only say that for the five years I have I known him he has been continually embroiled in quarrels and dissensions with all around him; I can positively affirm that for some time my family and one other were the only friends he had on the settlement, and I seriously compromised myself and injured my prospects in life by taking his part when a bailiff was in charge of his property; ….little did I know then the snake I was fostering…”

The ‘Pocock saga’ is long and complicated. There is no doubt that Reverend Zachary Pocock was a man of little moral substance. Police Court records reveal charges against Pocock for non-payment of wages and the abuse of his laundress as well as accusations of perjury and fraud. It is impossible to ascertain the truth of these claims but there is no question that Pocock was a self-serving and corrupt individual. It is probable that Pocock’s tenure at Emu Bay only lasted as long as it did due to the communities dependence on him for his medical qualifications. In 1860 Pocock stepped down from the ministry and moved to Launceston where he attempted to establish a medical practice before moving on to further ventures at Fingal and Green Ponds. He left Tasmania for New South Wales where he died in 1895.

Following Pocock’s departure, Reverend Richard Smith and Reverend Bernard Bourdillon’s tenures changed the fortunes of the church. Bourdillon arrived at Emu Bay in 1881 and it was under his tenure that the old chapel was replaced by a new church.

The old chapel was abandoned before the new church was completed in 1885. In May 1883 the Tasmanian reported:

“…Meanwhile winter was drawing on, and the present church was quite unfit for use. It had, therefore, been decided to erect at once a wooden building to serve temporarily as a place of worship/and to be used permanently for the Sunday-school and parochial meetings”.

This course of action was confirmed in a report published in the Hobart Mercury in April 1884:

"The old church, a poor wooden building, has been discarded, and a new brick one is being built. Services in the meantime are held in the church school-room".

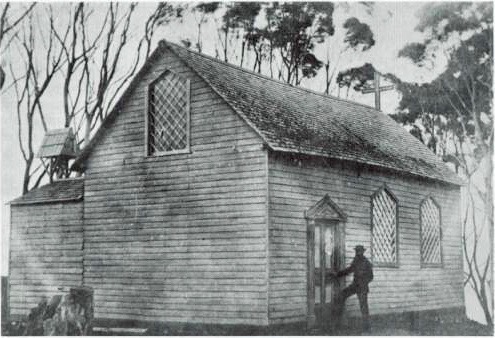

The only known photograph of the old chapel was taken in 1883 and shows Reverend Bourdillon closing the door after the last wedding celebration. The chapel as well as “Rocky Hill” which it stood on were destroyed by quarrying activity when the first breakwater was constructed in the bay.

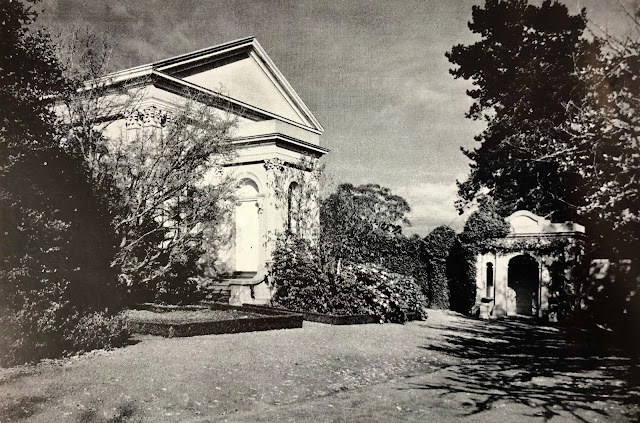

The new St George’s was built on the corner of Mount and Cattley Streets and this building will form the subject of a follow-up article on Burnie’s second Anglican Church.

“The first rector to be appointed to St George’s was the Reverend Zachary Pocock. Reverend Pocock’s time at Burnie was troubled and filled with conflict. In addition to his desecration of a local cemetery, Pocock was perceived as being arrogant and provocative, even resorting to physical altercation. As a result, attendance at the Chapel fell and locals petitioned the Bishop for Pocock’s removal”.

Zachary Pocock was the son of Reverend George Pocock, one-time incumbent of St Paul’s, Marylebone, London. Zachary Pocock was a man who had many irons in the fire. In addition to being an ordained minster he was a medical doctor and also seemed to have had aspirations to practice law. The first hint of trouble came in 1855 when ‘The People’s Advocate or True Friend of Tasmania’ reported on the difficulties the Anglican congregation was having with the new Missionary Chaplain:

“Again great complaints are made respecting the Revd Mr. Pocock, who it is said thinks more of his potato crops than the souls of those the government pay him to look after. The residents at the Bay are most anxious to get up a school for the education of their children, but Mr. Pocock declines taking any active part in getting the children educated because forsooth one of the residents spoke to him rather sharply upon the subject when applied to for a subscription”.

The report continued:

“On Monday week a meeting was called of the Protestant residents of Emu Bay, for the purpose of entering into a subscription to add to the government pay of the Rev. Mr. Pocock, and the assembly consisted of the two churchwardens and the Rev. gentleman himself. When remonstrated with upon his want of zeal in collecting his flock together and mixing more with his congregation, the Rev. gentleman replied, "the Church is there, they can come if they like, but I am not going to hawk religion about." The protestants also complain of the negligence of Mr. Pocock in not getting the burying ground consecrated, notwithstanding Mr. Pocock has been resident there upwards of two years, verily the Church is in danger at Emu Bay”.

In November of the same year a parishioner, James Munce, penned a lengthly letter of complaint to the Launceston Examiner in response to Pocock’s libellous defence of allegations made against him. The accusations made by Munce are astonishing:

“….They are established facts, that the church is not attended, that the burial ground is desecrated, and that Mr. Pocock is now, and has been for some time past, engaged in secular affairs. The first part is proved by the publishled list, and which I vouch for as correct. The ploughing up part of the burial ground, and sowing grain on it, and removing the fence around it, is a fact; and if selling potatoes, fruit, butter, milk, &c., and trafficking in timber, is not engaging in secular affairs, I don't know what is. I observe his remark that "there are not twenty adult members of the Church of England residing on the township of Emu Bay"; but I submit that the souls of children ought to be be as much attended to as adults; …. Mr. Pocock asserts that during twelve years' residence in the colony his character has been unimpeached; I can only say that for the five years I have I known him he has been continually embroiled in quarrels and dissensions with all around him; I can positively affirm that for some time my family and one other were the only friends he had on the settlement, and I seriously compromised myself and injured my prospects in life by taking his part when a bailiff was in charge of his property; ….little did I know then the snake I was fostering…”

The ‘Pocock saga’ is long and complicated. There is no doubt that Reverend Zachary Pocock was a man of little moral substance. Police Court records reveal charges against Pocock for non-payment of wages and the abuse of his laundress as well as accusations of perjury and fraud. It is impossible to ascertain the truth of these claims but there is no question that Pocock was a self-serving and corrupt individual. It is probable that Pocock’s tenure at Emu Bay only lasted as long as it did due to the communities dependence on him for his medical qualifications. In 1860 Pocock stepped down from the ministry and moved to Launceston where he attempted to establish a medical practice before moving on to further ventures at Fingal and Green Ponds. He left Tasmania for New South Wales where he died in 1895.

Following Pocock’s departure, Reverend Richard Smith and Reverend Bernard Bourdillon’s tenures changed the fortunes of the church. Bourdillon arrived at Emu Bay in 1881 and it was under his tenure that the old chapel was replaced by a new church.

The old chapel was abandoned before the new church was completed in 1885. In May 1883 the Tasmanian reported:

“…Meanwhile winter was drawing on, and the present church was quite unfit for use. It had, therefore, been decided to erect at once a wooden building to serve temporarily as a place of worship/and to be used permanently for the Sunday-school and parochial meetings”.

This course of action was confirmed in a report published in the Hobart Mercury in April 1884:

"The old church, a poor wooden building, has been discarded, and a new brick one is being built. Services in the meantime are held in the church school-room".

The only known photograph of the old chapel was taken in 1883 and shows Reverend Bourdillon closing the door after the last wedding celebration. The chapel as well as “Rocky Hill” which it stood on were destroyed by quarrying activity when the first breakwater was constructed in the bay.

The new St George’s was built on the corner of Mount and Cattley Streets and this building will form the subject of a follow-up article on Burnie’s second Anglican Church.

|

| A photograph of the original St George's church at Burnie (1883) - original source of photo not known - posted in Gravesites of Tasmania Facebook Group June 2017 |

|

| Launceston Examiner, Tuesday 21 December 1858 |

|

| Launceston examiner, Tuesday 30 December 1856 |

|

| The Cornwall Chronicle, Saturday 12 May 1860 |

Sources:

Courier, Wednesday 12 June 1850, page 2

Cornwall Chronicle, Tuesday 22 October 1850

Cornwall Chronicle, Tuesday 22 October 1850

People's Advocate or True Friend of Tasmania, Thursday 22 November 1855, page 3

Launceston examiner, Tuesday 30 December 1856, page 3

The Courier, Monday 1 June 1857, page 3

Launceston Examiner, Saturday 14 November 1857, page 3

Launceston Examiner, Tuesday 21 December 1858, page 2

The Cornwall Chronicle, Saturday 12 May 1860, page 6

Tasmanian, Saturday 5 May 1883.

The Hobart Mercury, Thursday 17 April 1884, page 3

Daily Telegraph, Wednesday 27 November 1895, page 4

Advocate, Wednesday 10 April 1935, page 10

Launceston examiner, Tuesday 30 December 1856, page 3

The Courier, Monday 1 June 1857, page 3

Launceston Examiner, Saturday 14 November 1857, page 3

Launceston Examiner, Tuesday 21 December 1858, page 2

The Cornwall Chronicle, Saturday 12 May 1860, page 6

Tasmanian, Saturday 5 May 1883.

The Hobart Mercury, Thursday 17 April 1884, page 3

Daily Telegraph, Wednesday 27 November 1895, page 4

Advocate, Wednesday 10 April 1935, page 10

Burnie: A Thematic History, Burnie City Council 2010 (Burnie City Heritage Survey)

Henslowe, Dorothea I and Hurburgh, Isa Our heritage of Anglican churches in Tasmania. Mercury-Walch, Moonah, Tas, 1978.

Comments

Post a Comment