No. 856 - Lindisfarne - Church of the Incarnation

Lindisfarne is an eastern shore suburb within the Greater Hobart area. It is named after "Lindisfarne House", a property situated in the adjoining suburb of Rosny. The area was originally known as Beltana but this was changed to Lindisfarne in 1903.

A recent article in Architecture Australia, “A church that projected progressivist ideals in Tasmanian suburbia”, Dr. Stuart King, a senior lecturer in architectural design and history at the University of Melbourne, draws the profession’s attention to Lindisfarne’s ‘Church of the Incarnation’.

King describes how global events influenced the design of Catholic churches in Tasmania during the progressive era of leadership under Archbishop Sir Guilford Young. In 1970 the construction of Sacred Heart Church at Newstead, [see No. 838 ] saw Archbishop Young’s intimate involvement in the planning of the Launceston church to accomodate the new form of participatory worship ushered in by the reforms by the Second Vatican Council. Lindisfarne’s Church of the Incarnation, which was built three years before Sacred Heart, was also a product of Guilford Young’s leadership which enabled and inspired church design by a progressive generation of Tasmanian architects. King writes:

“In October 1967, Tasmanian Catholic Archbishop Sir Guilford Young consecrated the Church of the Incarnation in Lindisfarne on Hobart’s eastern shore, the state’s first new, post-Second Vatican Council church. Commissioned by the parish priest, Father Michael Flynn, and designed by parishioner and architect Lindsay Wallace Johnston, the church has been overlooked in the slight histories of modern architecture in Tasmania. The state’s postwar ecclesiastical developments have typically been represented by the technological and metaphorical form-making of J. Esmond Dorney’s Pius X Catholic Church in Taroona (1957) and Cooper and Vincent’s St Patrick’s College Chapel in Launceston (1959). The design of the Church of the Incarnation presented an economical brutalist alternative. For Young, Flynn and Johnston it was a radical attempt to realize a liturgically driven, non-monumental, modern church architecture that aimed to build community…”.

King describes Guilford Young’s involvement in the new era of church building in Tasmania:

“Archbishop Guilford Young commenced his episcopate in Hobart in 1955, embarking upon a program of modernization and reform in the areas of church administration, education, worship and church building. He had a keen interest in architecture, but worked within a context of limited financial resources coupled with a growing demand for new churches. As he consecrated new churches, including Dorney’s Pius X Catholic Church, Young advocated “healthily modern” church architecture and, in 1958, he appointed Roderick Cooper, of Cooper and Vincent, as diocesan architect and began commissioning individual as well as standardized designs for modern churches for new industrial and housing commission subdivisions…..Young’s interest in modern architecture was allied to an international liturgical reform movement. The goal was to develop an architecture to aid in modernizing worship; this was approached in the fan-shaped planning of Cooper and Vincent’s soaring St Patrick’s College Chapel. The wider discourse posited that the essential function of a church building was to accommodate the performance of the liturgy, and especially the Eucharist, which was understood as an action involving the clergy and the congregation as a community”.

Archbishop Young was to work closely with the leading Tasmanian architects:

“At the Royal Australian Institute of Architects’ national convention in Hobart in 1960, he performed a Mass for architects, delivering a sermon on contemporary liturgical architecture. He advised his congregation that arriving at a modern church architecture would involve both scholarship and participation in the liturgy and community. He rallied against traditionalist church design while reasserting the church’s patrimony in architecture: “Liturgical in mind and spirit, the modern architecture will be saved from modernity for the sake of modernity.”

King details the design and construction of the Church of the Incarnation:

“In the new parish of Lindisfarne, Father Michael Flynn commissioned Johnston to design and superintend a new church. Johnston’s design for the Church of the Incarnation comprised an arrangement of concrete block prisms, presented in the local press as a comprehensive functional, aesthetic and social response to Second Vatican Council liturgy. A single interior volume, a sloping floor and open sanctuary were to unite the clergy and congregation in the liturgy. An interior palette of unfinished concrete block, timber and plywood was to maintain focus on liturgical proceedings. All “pretty stark,” as Flynn explained: “We have made a deliberate attempt to get away from the idea of a church as a monument ... We’re trying to get back to the idea of a church as a meeting place for Christians.”

However, this noble objective did not meet with universal approval by a largely conservative community. King concludes:

“….The finished architecture was largely disconnected from the experiences and expectations of the congregation, and the parish’s history records a disappointment in an unfamiliar architecture,.… Those perceptions have persisted and, in the absence of heritage protection, the church has, in recent years, been painted cream and carpeted blue. However, beneath the paintwork is a rare example of an Australian brutalist church allied to postwar liturgical reform. Tasmania has a rich heritage of ecclesiastical building, including notable works by architects such as A. W. N. Pugin and Alexander North. The state’s postwar buildings, including the Church of the Incarnation, extend that heritage and deserve protection and national recognition”.

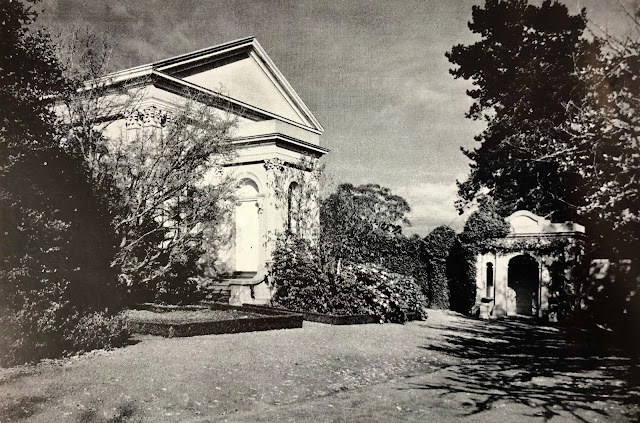

King’s observations are also borne out in the church’s exterior. When photographing the building I was challenged by shrubbery that substantially obscured the bold geometry of the church. Now that more than half a century has passed since the church opened, perhaps the time is not too far off when the Church of the Incarnation will receive the recognition it deserves for Johnston’s realisation of Guilford Young’s vision.

Photo credit: Photographer - R. Farrington (c. 1967), copy courtesy of Paul Johnston - as published in

A recent article in Architecture Australia, “A church that projected progressivist ideals in Tasmanian suburbia”, Dr. Stuart King, a senior lecturer in architectural design and history at the University of Melbourne, draws the profession’s attention to Lindisfarne’s ‘Church of the Incarnation’.

King describes how global events influenced the design of Catholic churches in Tasmania during the progressive era of leadership under Archbishop Sir Guilford Young. In 1970 the construction of Sacred Heart Church at Newstead, [see No. 838 ] saw Archbishop Young’s intimate involvement in the planning of the Launceston church to accomodate the new form of participatory worship ushered in by the reforms by the Second Vatican Council. Lindisfarne’s Church of the Incarnation, which was built three years before Sacred Heart, was also a product of Guilford Young’s leadership which enabled and inspired church design by a progressive generation of Tasmanian architects. King writes:

“In October 1967, Tasmanian Catholic Archbishop Sir Guilford Young consecrated the Church of the Incarnation in Lindisfarne on Hobart’s eastern shore, the state’s first new, post-Second Vatican Council church. Commissioned by the parish priest, Father Michael Flynn, and designed by parishioner and architect Lindsay Wallace Johnston, the church has been overlooked in the slight histories of modern architecture in Tasmania. The state’s postwar ecclesiastical developments have typically been represented by the technological and metaphorical form-making of J. Esmond Dorney’s Pius X Catholic Church in Taroona (1957) and Cooper and Vincent’s St Patrick’s College Chapel in Launceston (1959). The design of the Church of the Incarnation presented an economical brutalist alternative. For Young, Flynn and Johnston it was a radical attempt to realize a liturgically driven, non-monumental, modern church architecture that aimed to build community…”.

King describes Guilford Young’s involvement in the new era of church building in Tasmania:

“Archbishop Guilford Young commenced his episcopate in Hobart in 1955, embarking upon a program of modernization and reform in the areas of church administration, education, worship and church building. He had a keen interest in architecture, but worked within a context of limited financial resources coupled with a growing demand for new churches. As he consecrated new churches, including Dorney’s Pius X Catholic Church, Young advocated “healthily modern” church architecture and, in 1958, he appointed Roderick Cooper, of Cooper and Vincent, as diocesan architect and began commissioning individual as well as standardized designs for modern churches for new industrial and housing commission subdivisions…..Young’s interest in modern architecture was allied to an international liturgical reform movement. The goal was to develop an architecture to aid in modernizing worship; this was approached in the fan-shaped planning of Cooper and Vincent’s soaring St Patrick’s College Chapel. The wider discourse posited that the essential function of a church building was to accommodate the performance of the liturgy, and especially the Eucharist, which was understood as an action involving the clergy and the congregation as a community”.

Archbishop Young was to work closely with the leading Tasmanian architects:

“At the Royal Australian Institute of Architects’ national convention in Hobart in 1960, he performed a Mass for architects, delivering a sermon on contemporary liturgical architecture. He advised his congregation that arriving at a modern church architecture would involve both scholarship and participation in the liturgy and community. He rallied against traditionalist church design while reasserting the church’s patrimony in architecture: “Liturgical in mind and spirit, the modern architecture will be saved from modernity for the sake of modernity.”

King details the design and construction of the Church of the Incarnation:

“In the new parish of Lindisfarne, Father Michael Flynn commissioned Johnston to design and superintend a new church. Johnston’s design for the Church of the Incarnation comprised an arrangement of concrete block prisms, presented in the local press as a comprehensive functional, aesthetic and social response to Second Vatican Council liturgy. A single interior volume, a sloping floor and open sanctuary were to unite the clergy and congregation in the liturgy. An interior palette of unfinished concrete block, timber and plywood was to maintain focus on liturgical proceedings. All “pretty stark,” as Flynn explained: “We have made a deliberate attempt to get away from the idea of a church as a monument ... We’re trying to get back to the idea of a church as a meeting place for Christians.”

However, this noble objective did not meet with universal approval by a largely conservative community. King concludes:

“….The finished architecture was largely disconnected from the experiences and expectations of the congregation, and the parish’s history records a disappointment in an unfamiliar architecture,.… Those perceptions have persisted and, in the absence of heritage protection, the church has, in recent years, been painted cream and carpeted blue. However, beneath the paintwork is a rare example of an Australian brutalist church allied to postwar liturgical reform. Tasmania has a rich heritage of ecclesiastical building, including notable works by architects such as A. W. N. Pugin and Alexander North. The state’s postwar buildings, including the Church of the Incarnation, extend that heritage and deserve protection and national recognition”.

King’s observations are also borne out in the church’s exterior. When photographing the building I was challenged by shrubbery that substantially obscured the bold geometry of the church. Now that more than half a century has passed since the church opened, perhaps the time is not too far off when the Church of the Incarnation will receive the recognition it deserves for Johnston’s realisation of Guilford Young’s vision.

Photo credit: Photographer - R. Farrington (c. 1967), copy courtesy of Paul Johnston - as published in

Architecture Australia

Photo credit: Photographer - R. Farrington (c. 1967), copy courtesy of Paul Johnston - as published in

Architecture Australia

Sources:

King, Stuart: "A church that projected progressivist ideals in Tasmanian suburbia", Architecture Australia, Volume 108 Issue 3, May/June 2019

https://architectureau.com/articles/church-of-the-incarnation-hobart-tasmania-19651967/ - accessed 15-01-21

https://tasparish.org.au/church/church-incarnation-lindisfarne

Comments

Post a Comment