No. 944 - Hobart - St Virgil's Chapel - (1823 - c.1835 ) "Church on the Hill"

Hobart’s first Catholic church, St Virgil’s, was situated near St Patrick’s Street, in the vicinity of St Virgil’s Junior School campus. Known as St Virgil’s Chapel, this rudimentary place of worship dates back to 1823.

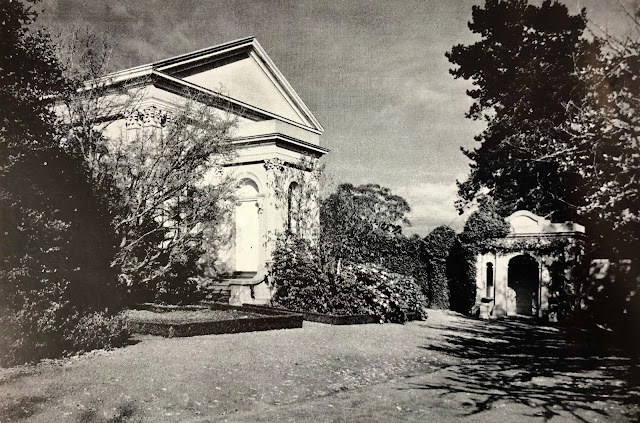

The wall of the Catholic cemetery viewed from Patrick Street. The Archbishop's residence

The chapel was built soon the arrival of Father Philip Conolly in April 1821, who was the first permanent Catholic priest appointed to Van Diemen’s Land. Shortly after Conolly’s arrival, the first official Mass held in Hobart took place in a store on Argyle Street which belonged to prominent Catholic businessman, Edward Curr. In June 1822 Curr became treasurer of a fund to build a church and a dwelling for Father Conolly. The property known as Killard (Gaelic for ‘church on the hill) stood on 14 acres of land, above Harrington Street, allotted by Governor Sorell for use by Catholics.

The date of the chapel’s completion and opening is not recorded although it was certainly in operation by mid 1823 as by this time there are references to it in advertisements in the Hobart Town Gazette and Van Diemen's Land Advertiser. St Virgil’s is the second Catholic church built in Australia with the foundation stone for the first being that of St Mary’s in Sydney, which was laid on 29 October 1821.

The chapel was dedicated to St. Virgilius, an Irish Saint, who was well-known in the early middle ages for astronomical knowledge and for considering the existence of the antipodes, anticipating Copernicus by eight centuries. It is an interesting tribute on the part of Father Conolly to choose St Virgilius as the patron of the first Catholic church in Tasmania.

No image of St Virgil’s chapel is known to exist and descriptions of the building reveal it to be a simple temporary structure which abutted Conolly’s presbytery.

In April 1823, Edward Curr wrote to Conolly, who was in Sydney at this time:

“I expect to have the little chapel in Hobart Town ceiled in a few weeks, after which I shall try what can be done towards building one on a larger scale of more permanent materials”.

Not much progress was made for in 1833 a description of the chapel by Dr. Hall reveals that the chapel was:

“A rude, barn-like structure, unceiled, unplastered, and boarded with loose warped boards, which would fly up by a careless tread on their extremities”.

In the same report Hall describes a “muddy trudge” up the hill to the “densely crowded chapel” mainly filled with soldiers from the local regiments. Hall complained that the “service and accessories were of a rude and primitive character, and when Father Conolly thrust his way among the people with an old hat to make the collection at the offertory, my better half…was astounded”.

Another report of the chapel’s appearance, also from observations made in 1833, was written by Dr. Ullerthorne:

“I found the chapel in a most disgraceful state….built of boards with the Government broad arrow on them, the floor had never been laid down, but consisted of loose planks with their edges curled up by the heat, as well as loose under the knees of the people…There was a coating of loose plaster on the wall behind the altar, covered with black glazed cotton all over filth, that had hung their since the death of George IV, the altar, a framework of wood, had a similar black glazed cotton for the frontal, and dirty altar cloths were covered with stains…..The space between the two ends of the altar and the walls were refuge holes for all kinds of rubbish such as old hats, buckets, mops and brooms. There were no steps to the altar, but the same loose planks that formed the entire floor, and no seats for the people”.

From these two accounts it would be easy to reach the conclusion that Father Conolly was remissful in his duty as the colony’s sole Catholic priest. This assessment would not be fair or accurate given the enormity of Conolly’s responsibilities and the challenging conditions in which he operated. The story of Father Conolly time at Hobart is is both fascinating and controversial but cannot be done justice in this short article. Conolly certainly had bitter enemies in the Catholic community and these colour reports of the priest and his chapel.

Perhaps the most challenging of Conolly’s duties was as chaplain attending those condemned to execution. One anecdote is recalled by Reverend Father Martin Gilleran:

“On one occasion be put into writing a dying statement made by a condemned man. Governor Arthur demanded the manuscript, but when he got it neither he nor his secretaries could read it. It was written in the Irish language”.

St Virgil’s Chapel was in use for about a dozen years. In this time Conolly established a Catholic cemetery alongside the chapel and started on the construction on a stone church in 1835, although this was not completed.

The cemetery was established in 1825. In August of that year the Colonial Times and Tasmanian Advertiser noted:

“It may not be generally known, that adjoining the Roman Catholic Chapel in Hobart Town, a large site of ground has been given by the government as its burial place - Several persons have already been interred there; among whom was Private Thomson, of the 40th, who was followed to the grave on Saturday last by a detachment of that company”.

The last burial at the cemetery was 1872 and the site was redeveloped in 1916 with the remains of about 1000 Catholics reinterred at Cornelian Bay between 1916 and 1919. Father Conolly died in 1839 at the age of 53 and was buried in the cemetery he had established, along with his brother Patrick and his sister Catherine.

The esteem in which Conolly was held is at the time of his death is evident in a report published in The Tasmanian:

“The body was followed by about two hundred persons, amongst whom were some of the most respectable and influential gentlemen of the Colony, besides several military officers, and about fifty men of the 21st and 51st Regiments”.

In 1916 Father Philip Conolly’s remains were reinterred within St Mary’s Cathedral.

A link to the original St Virgil’s chapel is represented in the present-day chapel of St Virgil (at Guilford Young College) built in 1939 at the site for the first St Virgil's College, which was opened by the Christian Brothers in 1911.

The date of the chapel’s completion and opening is not recorded although it was certainly in operation by mid 1823 as by this time there are references to it in advertisements in the Hobart Town Gazette and Van Diemen's Land Advertiser. St Virgil’s is the second Catholic church built in Australia with the foundation stone for the first being that of St Mary’s in Sydney, which was laid on 29 October 1821.

The chapel was dedicated to St. Virgilius, an Irish Saint, who was well-known in the early middle ages for astronomical knowledge and for considering the existence of the antipodes, anticipating Copernicus by eight centuries. It is an interesting tribute on the part of Father Conolly to choose St Virgilius as the patron of the first Catholic church in Tasmania.

No image of St Virgil’s chapel is known to exist and descriptions of the building reveal it to be a simple temporary structure which abutted Conolly’s presbytery.

In April 1823, Edward Curr wrote to Conolly, who was in Sydney at this time:

“I expect to have the little chapel in Hobart Town ceiled in a few weeks, after which I shall try what can be done towards building one on a larger scale of more permanent materials”.

Not much progress was made for in 1833 a description of the chapel by Dr. Hall reveals that the chapel was:

“A rude, barn-like structure, unceiled, unplastered, and boarded with loose warped boards, which would fly up by a careless tread on their extremities”.

In the same report Hall describes a “muddy trudge” up the hill to the “densely crowded chapel” mainly filled with soldiers from the local regiments. Hall complained that the “service and accessories were of a rude and primitive character, and when Father Conolly thrust his way among the people with an old hat to make the collection at the offertory, my better half…was astounded”.

Another report of the chapel’s appearance, also from observations made in 1833, was written by Dr. Ullerthorne:

“I found the chapel in a most disgraceful state….built of boards with the Government broad arrow on them, the floor had never been laid down, but consisted of loose planks with their edges curled up by the heat, as well as loose under the knees of the people…There was a coating of loose plaster on the wall behind the altar, covered with black glazed cotton all over filth, that had hung their since the death of George IV, the altar, a framework of wood, had a similar black glazed cotton for the frontal, and dirty altar cloths were covered with stains…..The space between the two ends of the altar and the walls were refuge holes for all kinds of rubbish such as old hats, buckets, mops and brooms. There were no steps to the altar, but the same loose planks that formed the entire floor, and no seats for the people”.

From these two accounts it would be easy to reach the conclusion that Father Conolly was remissful in his duty as the colony’s sole Catholic priest. This assessment would not be fair or accurate given the enormity of Conolly’s responsibilities and the challenging conditions in which he operated. The story of Father Conolly time at Hobart is is both fascinating and controversial but cannot be done justice in this short article. Conolly certainly had bitter enemies in the Catholic community and these colour reports of the priest and his chapel.

Perhaps the most challenging of Conolly’s duties was as chaplain attending those condemned to execution. One anecdote is recalled by Reverend Father Martin Gilleran:

“On one occasion be put into writing a dying statement made by a condemned man. Governor Arthur demanded the manuscript, but when he got it neither he nor his secretaries could read it. It was written in the Irish language”.

St Virgil’s Chapel was in use for about a dozen years. In this time Conolly established a Catholic cemetery alongside the chapel and started on the construction on a stone church in 1835, although this was not completed.

The cemetery was established in 1825. In August of that year the Colonial Times and Tasmanian Advertiser noted:

“It may not be generally known, that adjoining the Roman Catholic Chapel in Hobart Town, a large site of ground has been given by the government as its burial place - Several persons have already been interred there; among whom was Private Thomson, of the 40th, who was followed to the grave on Saturday last by a detachment of that company”.

The last burial at the cemetery was 1872 and the site was redeveloped in 1916 with the remains of about 1000 Catholics reinterred at Cornelian Bay between 1916 and 1919. Father Conolly died in 1839 at the age of 53 and was buried in the cemetery he had established, along with his brother Patrick and his sister Catherine.

The esteem in which Conolly was held is at the time of his death is evident in a report published in The Tasmanian:

“The body was followed by about two hundred persons, amongst whom were some of the most respectable and influential gentlemen of the Colony, besides several military officers, and about fifty men of the 21st and 51st Regiments”.

In 1916 Father Philip Conolly’s remains were reinterred within St Mary’s Cathedral.

A link to the original St Virgil’s chapel is represented in the present-day chapel of St Virgil (at Guilford Young College) built in 1939 at the site for the first St Virgil's College, which was opened by the Christian Brothers in 1911.

* In 2021 the bicentenary of Philip Conolly's arrival in Tasmania was celebrated. A commemorative book written by Nick Brodie was commissioned by the Archdiocese of Hobart to mark this event. This is a recommended read for a detailed history of the life of Philip Conolly. Further information is available at this link:

|

| Hobart Town Gazette and Van Diemen's Land Advertiser, Saturday 22 June1822, page 1 |

|

| The chapel's location (C) is precisely marked on the map as midway between Patrick Street and Brisbane Street - source: Libraries Tasmania - Item No. AF394/1/5 (undated) |

|

| The Catholic Cemetery on Barrack Street which was located above St Virgil's - dated c1870-1890 - Libraries Tasmania online collection |

The wall of the Catholic cemetery viewed from Patrick Street. The Archbishop's residence

can be seen to the left of the photograph. c.1905 - Libraries Tasmania online collection

|

| Philip Conolly's headstone at St Vigil's Cemetery - source: thepuginsociety.co.uk |

|

| A plaque in St Mary's Cathedral |

|

| St Virgil's Chapel - at Guilford Young College |

Sources:

Much of the material for this article has been drawn from Planting a faith : Hobart's Catholic story in word and picture by W. T. Southerwood, Speciality Press, 1970.

Other sources used include:

Hobart Town Gazette and Van Diemen's Land Advertiser, Saturday 2 February 1822, page 1

Hobart Town Gazette and Van Diemen's Land Advertiser, Saturday 22 June1822, page 1

Colonial Times and Tasmanian Advertiser, Friday 19 August 1825, page 4

The Austral-Asiatic Review, Tasmanian and Australian Advertiser, Tuesday 6 August 1839, page 2

The Tasmanian, Friday 9 August 1839, page 6

Tasmanian News, Thursday 28 July 1904, page 4

Mercury, Saturday 31 December 1904, page 2

Mercury, Saturday 6 January 1906, page 5

World, Friday 11 April 1919, page 2

Mercury, Monday 7 August 1939, page 5

http://www.thepuginsociety.co.uk/uploads/2/0/5/6/20562880/newsletter_77.pdf

https://www.utas.edu.au/library/companion_to_tasmanian_history/C/Philip%20Conolly.htm

Comments

Post a Comment