No. 969 - Adamsfield - Ministering on the "Ossyfield"

Adamsfield was an isolated mining settlement situated in the rugged southwest, approximately 10 kilometres west of the Florentine Road and about 5 kilometres from Lake Gordon. Now a ghost town, it was established when rich deposits of osmiridium were found at Adams River Field in the 1920s. At this time osmiridium had a value of about £30 per ounce; several times the value of gold. A mining rush began in 1925 and a camp of about 1,000 people emerged. By the late 1930s the rush was over and by the 1960s commercial mining activity had ceased altogether.

At its peak Adamsfield’s population was sizeable and the township had a community hall, post office, a field hospital, a school and a handful of shops. Although no churches were established, religious services were held in the community hall. Most of Tasmania’s early mining settlements invariably had at least one church established but Adamsfield’s remote location and the short duration of its population peak, mitigated against a permanent church being built. However, there is still a story to tell about religious life in this isolated settlement.

At the time of Tasmania’s first mining boom in the 1870s, preachers, ministers and priests would be attracted to remote bush settlements to save and tend to the souls of the miners. These were a fervid generation of devout men who travelled on horseback on perilous missions to bring God’s word to the wilderness.

By the 1920s, clerical life had become settled and sedate thus the challenge of ministering to the people of Adamsfield presented a significant challenge to the established churches. This article’s focus is on how this challenge was addressed with several ‘expeditions’ to the osmiridium fields.

The first church service held at Adamsfield took place soon after mining began. In January 1926 the Tasmanian Council of Churches announced that Reverend E.C. MacIntosh Brown, a Baptist minister, was to “take up evangelistic work at Adamsfield amongst the diggers for six months”. MacIntosh Brown was in fact to spend two years on the osmirdium fields.

Shortly after McIntosh Brown’s appointment, the Anglican’s were to follow suit. In February 1926, Bishop Robert Hay dispatched Reverend C.W. Wilson, the rector of St James’, New Town, to the mining camp: The Mercury reported:

“The Rev. C. W. Wilson,…. spent last week on the Adams River osmiridium field, for the purpose of furnishing the Church of England authorities with a report on the conditions prevailing, and the best means of attending to the spiritual needs of the many Church of England men there”.

Wilson reported:

“The field extends roughly north and south for about five miles, and is about 2½ miles wide. Access is gained by a corduroy pack track from Fitzgerald to the post office in the centre of the field, about 25 miles long, through beautiful scenery and copious mud. The old wearisome climb over The Thumbs is now a thing of the past, and the journey can be made on foot or pack horse; in either case four miles an hour is "good going." The nucleus of the Adamsfield township consists of a dozen slab buildings, post office, police quarters, butcher, baker, several stores, and a billiard room 18 x 30, which is used for meetings, and where the first sermon was preached on Sunday, February 21, to a congregation of about 100 men. The miner lives under canvas, and there are about 750 men and 15 women on the field, and there appears to be at least two years' work in sight for about 400 of them. Deep boring should bring further discoveries, and prospecting may disclose additional supplies of osmiridium, but it is no place for a man without capital to carry him on for a while. Good water for domestic purposes is obtained from two wells, sunk in tho middle of the field, and there is plenty in the creeks, etc., for mining purposes. Conditions now are not bad, but the winters are very severe, and frequently snow causes cessation of work. The church's ministrations will he warmly welcomed, and an effort will be made to secure and place a clergyman in residence on the field. The most disturbing feature is the uncertainty as to the market price of the metal, and this, unless stabilised, will undoubtedly affect the future development and permanency of one of the 'livest' examples of the mining industry in Tasmania today.”

By 1927, mining activity slowed and Adamsfield’s population had declined significantly and consequently religious services became less frequent. In 1931 the Tasmanian Council of Churches again investigated establishing a church at the settlement and sent to ministers to survey Adamsfield’s “religious needs”. The report produced by Reverend J. Crookson describes the experiences of the two men over a period of three days and provide a fascinating glimpse into life at Adamsfield:

“The Rev. C. Matear and I visited Adamsfield on Monday, November 2, and remained till Wednesday, November 4. The distance from Fitzgerald, the railway terminus, is about 27 miles, along a track of about 4ft. wide through forest and jungle. The scenery in places on the way is very fine. This is the only definite approach to the field. All provisions are taken on pack-horses".

"There are about 250 people on the field, including about 30 women and a few children. At the little day school, which we visited at the invitation of Mr. Cole, the teacher, we found seven children present. There are eight on the roll, and of these four are Roman Catholics, children must be six years of age before being put on the roll. We found it impossible, in the time at our disposal, to get accurate figures of the denominations represented, but we feel sure that 75 per cent, may be safely set down as belonging to the Church of England and Roman Catholic Churches".

"The field is very scattered, and the distances between working claims in many cases are considerable. There are only rough tracks, often not easy to negotiate. The workings are alluvial, except In the old part of the field, known as the Thumbs, where there is a lode being worked at depths from 20ft. to 70ft. Good results are obtainable from this lode. At present miners are not finding much metal, and, as the price is low £13 10s. per ounce on the field, many are making only a bare living. Those who are financial enough to bring water to these claims from reservoirs supplied by the Government are able by sluicing to put through large quantities of dirt, and so, of course, get a better return, but those who use only the dish for mashing got only enough to purchase provisions. The cost of making races and purchase of piping for sluicing range up to £300".

"There is a very small, township, with three stores, a bank, and hall. All the buildings are very primitive, and conditions are rough, but we have reason to believe that for a mining town so isolated and remote the life and morals of the people are above the average usually found In such places. We met men who seemed to be of a fine type and, questioning some of them, were glad to hear their good opinion of the people generally. Sister Johnston, the bush nurse, who has lived among the people for a year, told us that she likes them very much, and knew of nothing very undesirable. There is a Vigilance Committee, which seems to function well, keeping a strict oversight of dances held in the hall, and allowing no drink on the premises".

"We held a service on the Tuesday evening. There were 17 people present, but, as the miners work very late, and then come to their huts wet and weary, and often a mile to a mile and a half to walk, we could hardly expect a much larger attendance. We did not take the attendance as indicative of what might be expected on a Sunday. We received fine reports of the work done by the Rev. McIntosh Brown. He seems to have won the good opinion of all. Mr. Brown left the field when the population had dwindled to about 80. There will probably be a fluctuating population, more especially during the summer months, when water is scarce, but all of those whom we met are of the opinion that the field will last for years, some said 20 years. If the value of metal rises there will no doubt be an Influx of men, but even as things are there is employment for about the present number of men".

"We arranged for a Sunday school to be opened. Mr. Cole and Sister Johnston agreed to share the oversight. Mr. Matear has already sent on lessons and teachers' helps. There are not many children, but it is important that they should have some religious teaching”.

In 1932 the Council of Churches again dispatched a minister to report on the spiritual state of affairs at Adamsfield. In May 1932, Reverend Paton, who was a Presbyterian minister, reported to the Council:

“Besides giving interesting sidelights on the 20-odd miles journey on horse back from Fitzgerald, along the corduroy bush track, and some photographs of the country, which abounds in magnificent scenery, Mr. Paton told of his cordial reception at the osmiridium field. About 40 persons attended the evening service in the hall, showing a real community appreciation of the opportunity of public worship. Mr. T. S. Cole (school teacher) had made the local arrangements. …Mr. Paton spend Monday on “the field,” and learned something of the diggers' tolls and difficulties. He expressed himself as being greatly Impressed with the courageous outlook of the men and women who, in spite of the depressed market for osmiridium, and its general scarcity, cheerfully face the daily round. There are about 250 or 300 people at Adamsfield, including "SouthEnd" and other settlements. Local satisfaction was expressed at the intention of the council to send a minister to Adamsfield quarterly….”.

By the mid 1930s it appears that visits from ministers from the ‘Council of Churches’ had ceased as the settlement’s population dwindled. While no church was established at Adamsfield, spiritual life on the osmiridium fields represents an important element of a bigger story about one of Tasmania's last mining boomtowns.

Sources:

At its peak Adamsfield’s population was sizeable and the township had a community hall, post office, a field hospital, a school and a handful of shops. Although no churches were established, religious services were held in the community hall. Most of Tasmania’s early mining settlements invariably had at least one church established but Adamsfield’s remote location and the short duration of its population peak, mitigated against a permanent church being built. However, there is still a story to tell about religious life in this isolated settlement.

At the time of Tasmania’s first mining boom in the 1870s, preachers, ministers and priests would be attracted to remote bush settlements to save and tend to the souls of the miners. These were a fervid generation of devout men who travelled on horseback on perilous missions to bring God’s word to the wilderness.

By the 1920s, clerical life had become settled and sedate thus the challenge of ministering to the people of Adamsfield presented a significant challenge to the established churches. This article’s focus is on how this challenge was addressed with several ‘expeditions’ to the osmiridium fields.

The first church service held at Adamsfield took place soon after mining began. In January 1926 the Tasmanian Council of Churches announced that Reverend E.C. MacIntosh Brown, a Baptist minister, was to “take up evangelistic work at Adamsfield amongst the diggers for six months”. MacIntosh Brown was in fact to spend two years on the osmirdium fields.

Shortly after McIntosh Brown’s appointment, the Anglican’s were to follow suit. In February 1926, Bishop Robert Hay dispatched Reverend C.W. Wilson, the rector of St James’, New Town, to the mining camp: The Mercury reported:

“The Rev. C. W. Wilson,…. spent last week on the Adams River osmiridium field, for the purpose of furnishing the Church of England authorities with a report on the conditions prevailing, and the best means of attending to the spiritual needs of the many Church of England men there”.

Wilson reported:

“The field extends roughly north and south for about five miles, and is about 2½ miles wide. Access is gained by a corduroy pack track from Fitzgerald to the post office in the centre of the field, about 25 miles long, through beautiful scenery and copious mud. The old wearisome climb over The Thumbs is now a thing of the past, and the journey can be made on foot or pack horse; in either case four miles an hour is "good going." The nucleus of the Adamsfield township consists of a dozen slab buildings, post office, police quarters, butcher, baker, several stores, and a billiard room 18 x 30, which is used for meetings, and where the first sermon was preached on Sunday, February 21, to a congregation of about 100 men. The miner lives under canvas, and there are about 750 men and 15 women on the field, and there appears to be at least two years' work in sight for about 400 of them. Deep boring should bring further discoveries, and prospecting may disclose additional supplies of osmiridium, but it is no place for a man without capital to carry him on for a while. Good water for domestic purposes is obtained from two wells, sunk in tho middle of the field, and there is plenty in the creeks, etc., for mining purposes. Conditions now are not bad, but the winters are very severe, and frequently snow causes cessation of work. The church's ministrations will he warmly welcomed, and an effort will be made to secure and place a clergyman in residence on the field. The most disturbing feature is the uncertainty as to the market price of the metal, and this, unless stabilised, will undoubtedly affect the future development and permanency of one of the 'livest' examples of the mining industry in Tasmania today.”

By 1927, mining activity slowed and Adamsfield’s population had declined significantly and consequently religious services became less frequent. In 1931 the Tasmanian Council of Churches again investigated establishing a church at the settlement and sent to ministers to survey Adamsfield’s “religious needs”. The report produced by Reverend J. Crookson describes the experiences of the two men over a period of three days and provide a fascinating glimpse into life at Adamsfield:

“The Rev. C. Matear and I visited Adamsfield on Monday, November 2, and remained till Wednesday, November 4. The distance from Fitzgerald, the railway terminus, is about 27 miles, along a track of about 4ft. wide through forest and jungle. The scenery in places on the way is very fine. This is the only definite approach to the field. All provisions are taken on pack-horses".

"There are about 250 people on the field, including about 30 women and a few children. At the little day school, which we visited at the invitation of Mr. Cole, the teacher, we found seven children present. There are eight on the roll, and of these four are Roman Catholics, children must be six years of age before being put on the roll. We found it impossible, in the time at our disposal, to get accurate figures of the denominations represented, but we feel sure that 75 per cent, may be safely set down as belonging to the Church of England and Roman Catholic Churches".

"The field is very scattered, and the distances between working claims in many cases are considerable. There are only rough tracks, often not easy to negotiate. The workings are alluvial, except In the old part of the field, known as the Thumbs, where there is a lode being worked at depths from 20ft. to 70ft. Good results are obtainable from this lode. At present miners are not finding much metal, and, as the price is low £13 10s. per ounce on the field, many are making only a bare living. Those who are financial enough to bring water to these claims from reservoirs supplied by the Government are able by sluicing to put through large quantities of dirt, and so, of course, get a better return, but those who use only the dish for mashing got only enough to purchase provisions. The cost of making races and purchase of piping for sluicing range up to £300".

"There is a very small, township, with three stores, a bank, and hall. All the buildings are very primitive, and conditions are rough, but we have reason to believe that for a mining town so isolated and remote the life and morals of the people are above the average usually found In such places. We met men who seemed to be of a fine type and, questioning some of them, were glad to hear their good opinion of the people generally. Sister Johnston, the bush nurse, who has lived among the people for a year, told us that she likes them very much, and knew of nothing very undesirable. There is a Vigilance Committee, which seems to function well, keeping a strict oversight of dances held in the hall, and allowing no drink on the premises".

"We held a service on the Tuesday evening. There were 17 people present, but, as the miners work very late, and then come to their huts wet and weary, and often a mile to a mile and a half to walk, we could hardly expect a much larger attendance. We did not take the attendance as indicative of what might be expected on a Sunday. We received fine reports of the work done by the Rev. McIntosh Brown. He seems to have won the good opinion of all. Mr. Brown left the field when the population had dwindled to about 80. There will probably be a fluctuating population, more especially during the summer months, when water is scarce, but all of those whom we met are of the opinion that the field will last for years, some said 20 years. If the value of metal rises there will no doubt be an Influx of men, but even as things are there is employment for about the present number of men".

"We arranged for a Sunday school to be opened. Mr. Cole and Sister Johnston agreed to share the oversight. Mr. Matear has already sent on lessons and teachers' helps. There are not many children, but it is important that they should have some religious teaching”.

In 1932 the Council of Churches again dispatched a minister to report on the spiritual state of affairs at Adamsfield. In May 1932, Reverend Paton, who was a Presbyterian minister, reported to the Council:

“Besides giving interesting sidelights on the 20-odd miles journey on horse back from Fitzgerald, along the corduroy bush track, and some photographs of the country, which abounds in magnificent scenery, Mr. Paton told of his cordial reception at the osmiridium field. About 40 persons attended the evening service in the hall, showing a real community appreciation of the opportunity of public worship. Mr. T. S. Cole (school teacher) had made the local arrangements. …Mr. Paton spend Monday on “the field,” and learned something of the diggers' tolls and difficulties. He expressed himself as being greatly Impressed with the courageous outlook of the men and women who, in spite of the depressed market for osmiridium, and its general scarcity, cheerfully face the daily round. There are about 250 or 300 people at Adamsfield, including "SouthEnd" and other settlements. Local satisfaction was expressed at the intention of the council to send a minister to Adamsfield quarterly….”.

By the mid 1930s it appears that visits from ministers from the ‘Council of Churches’ had ceased as the settlement’s population dwindled. While no church was established at Adamsfield, spiritual life on the osmiridium fields represents an important element of a bigger story about one of Tasmania's last mining boomtowns.

|

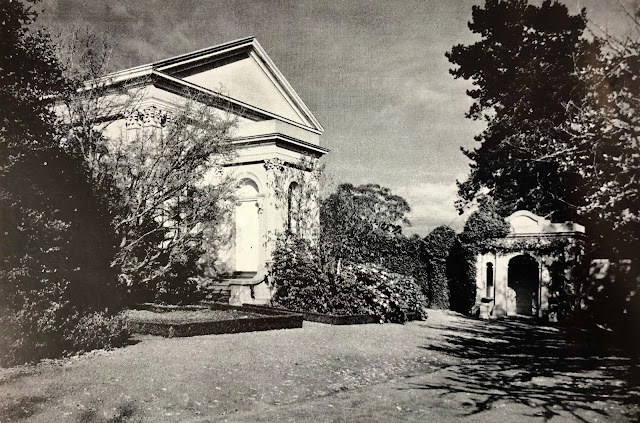

| Adamsfield (undated) Libraries Tasmania (Archives Office) - Jack Thwaites and Family (NG1155) |

|

| Adamsfield - (undated) Libraries Tasmania (Archives Office)- Jack Thwaites and Family (NG1155) |

|

| Archives Office of Tasmania - Libraries Tasmania online collection (AF819-1-2) |

Sources:

The News, Monday 21 December 1925, page 3

Mercury, Saturday 23 January 1926, page 8

Mercury, Thursday 4 March 1926, page 7

Mercury, Monday 16 November 1931, page 3

Mercury, Monday 16 May 1932, page 2

Examiner, Monday 9 May 1932, page 5

Examiner, Saturday 10 September 1932, page 5

Mercury, Saturday 17 December 1932, page 7

https://www.abc.net.au/local/stories/2008/09/29/2377022.htm

https://www.placenames.tas.gov.au

Comments

Post a Comment