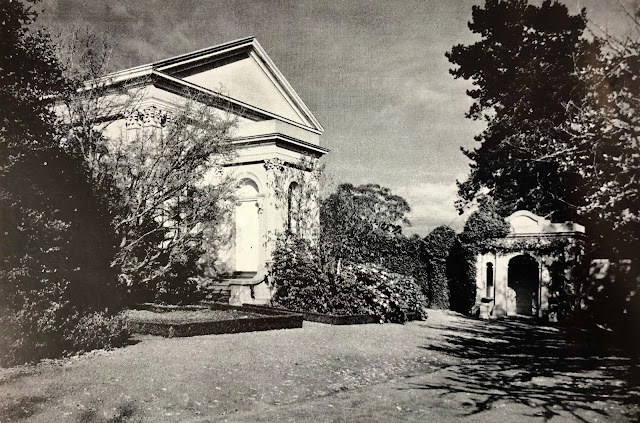

No. 995 - Wybalenna Chapel - "The Flinders Island Bastille"

The former chapel at Wybalenna is a most poignant symbol of one of the most shameful periods in the history of modern Australia. Purportedly the settlement at Wybalenna was established for the purpose of ‘civilising' and ‘Christianising’ aboriginal survivors of Tasmania’s colonial wars. More accurately it was an enterprise disguised with a “veneer of civilisation” which deliberately set out to extinguish an ancient culture.

The following information is drawn from a ‘fact sheet’ written by an unnamed author for “Aboriginal Heritage Tasmania”, a Division of the Tasmanian Government’s Department of Primary Industries, Parks,Water and Environment:

“Wybalenna is one of the most significant Aboriginal historical places in Tasmania. It is located on the west coast of Flinders Island, the largest island in the eastern part of Bass Strait. In response to the escalating conflict between Aboriginal people and colonists during the 1820s, the colonial authorities discussed options to remove the Aboriginal people from their lands.The activities of ‘roving parties’ in the 1820s, George Robinson’s so-called ‘friendly mission’ in 1829 – 1831, and the Black Line in 1830, led to an agreement – or, some say, a treaty – between Aboriginal clan leaders and Governor Arthur in October 1831.The agreement led to the progressive removal of Aboriginal people from mainland Tasmania from 1831 to 1835.

After trialling several sites to house the removed Aboriginal people Commandant W J Darling settled on the current site on Flinders Island in February 1833. It was named ‘Wybalenna’. This was chosen as it meant ‘Black man’s houses’ in the language of the Ben Lomond people, the largest Aboriginal nation at the site.

In 1833, there were 57 Aboriginal people and 50 colonists at Wybalenna. From 1832 to 1835 about a dozen children were removed from Wybalenna to attend the Orphan School in Hobart. George Robinson became Commandant of the settlement in October 1835 and the Aboriginal people who had travelled with him since 1830, including Trukanini and Wurati, arrived at Wybalenna at this time. Several Aboriginal people from New South Wales and South Australia were also at Wybalenna for a time.

Schooling at Wybalenna began in 1834.The teachings included reading and writing in English, with a select group of Aboriginal children as the teachers – usually children of the clan leaders. As well as the weekday schools a Saturday evening school began in 1836. Male clan leaders spoke in their first language to their own clan, then to all Aboriginal people in the ‘pidgin’ ‘language of the settlement’. The school and chapel were located in one of the huts belonging to the Ben Lomond clan until July 1838 when the brick chapel was built. Sunday church services were announced with the ringing of a bell and raising the Union Jack. Attendance was not compulsory and less than one third of Aboriginal people attended.

In September 1836, two young men aged about 15,Walter Arthur (Ben Lomond) and Thomas Bruny (an orphan), began writing the ‘Aboriginal or Flinders Island Chronicle’. In the beginning, Robinson supervised their writing very closely but gradually the writers gained more independence. This is the earliest known newspaper written by Aboriginal people in Australia.

Following the departure of George Robinson to Port Philip (now Victoria) in February 1839, there was a dramatic reduction in resources provided to the Settlement. Most of the convicts and soldiers were removed. Doctor Jeanneret was appointed Commandant in 1842. Children were again removed to the Orphan School against their parents’ wishes. In February 1846, Walter Arthur and other Aboriginal people petitioned Queen Victoria to prevent Jeanneret returning. In spite of the petition, Jeanneret was reinstated. Conflict escalated and in 1847, Governor Denison ordered the closure of Wybalenna. By the time the settlement closed in 1847, approximately 130 people had died at Wybalenna. On 18 October 1847, the remaining 14 men, 23 women and 10 children were removed from Wybalenna and taken to the former convict station at putalina / Oyster Cove”.

Of the chapel itself, there is little information about it or contemporary accounts of its use. Indeed, the only substantial account of a religious service at Wybalenna dates to 1836, prior to the construction of the brick chapel in 1838. It is hard to assess the accuracy of the report published in the Hobart Town Courier, which has the appearance of propaganda piece in that it presented life at the settlement as idyllic:

“A temporary structure has also been put up as a church, and their voluntary attendance is we learn universal. Several have learned to join in the church music, in which they appear to take much delight. The observance of the sabbath, indeed, serves in that as in all other cases, as one of the best of all means, and better than any that man could devise, for the advancement of civilization. At day light on that day the Union Jack is hoisted at the mast head on the little mount that overlooks the village, which is taken as a signal to clean and prepare themselves in their best attire for the day of rest, and when the bell begins to toll to church they may be seen collecting round the church door”.

In stark contrast to this picture, Launceston’s Cornwall Chronicle published an astonishing and prescient view of the settlement which it called the Flinders Island Bastille:

“… [We] repeat our conviction of the positive necessity for an investigation into the management of it, and of every matter connected with it. Certain it is, that in a very short space of time three fourths of the Aboriginal Natives have died! If they are British subjects, their fellow subjects are privileged to be made acquainted with the cause of the extraordinary loss of life. It does not follow, that because these poor creatures have been forcibly transported to a desert island, they should die off like rotten sheep, without receiving even the common sympathy of their fellow men. It is true that they are of a different complexion to the invaders of their country; it is true, that being goaded on by cruelties to self defence, they sometimes retaliated upon their oppressors; and, perhaps, humane policy it was on the part of their oppressors, to remove them away from their native land. The policy of the measure, nevertheless, does not constitute it a just measure; the rightful inheritors of this land have been forcibly transported to a desert island, where, under the deceptive colour of humanity, they are forcibly detained— are forcibly subjected to a restraint and discipline, that will only terminate in their annihilation. What could Colonists have to fear from these poor, abused creatures, were they permitted to enjoy their native air in undisturbed freedom? Has our population of nearly 50,000 Englishmen, to fear injury from less than 100 harmless and unoffending natives, enjoying that liberty which is no less their right, than necessary for their existence? Away with such worse than childish fears. The net of detaining the rightful possessors of this land in captivity at Flinders' Island, is an act of political atrocity, that is disgraceful to ourselves and our country, and has but one parallel in the annals of civilized nations- that of Colonel Arthur inhumanly butchering, by the hands of the common hangman, some of this same race of native blacks”.

Upon settlement’s closure in 1847, Wybalenna’s brick chapel would have been in use for only 8 years. Like Tasmania’s ‘first people’, it has miraculously survived. After 1854, it was used as a barn and stood in a paddock, surrounded by a few grassy mounds, covering the remnants of the settlement’s ruined buildings. In 1970, ironically exactly 200 years after Captain Cook’s arrival, the National Trust of Australia, initiated steps to acquire and restore the Wybalenna Chapel. The owner of the building, Thomas Morton, agreed to swop the chapel in exchange for a new shearing shed.

During the 1970s and 1980s increased interest in the site, and the cemetery in particular, led to archaeological surveys and the making of the film, ‘Black Man’s Houses’. In late 1991 a small group of approximately ten Aborigines re-occupied the site and made it clear that they had reclaimed the area in the name of the Aborigines living on Flinders Island. This was clearly broadcast to the world with a sign hung on the gate which read: “You are now entering Aboriginal land, please respect our culture”.

In 1999 the Tasmanian Government, under the Aboriginal Lands Act (1995), returned the land to the Tasmanian Aboriginal community. The title of the land was vested with the Aboriginal Land Council of Tasmania and Wybalenna’s management and preservation is under the care of the Flinders Island Aboriginal Association Incorporated.

The following information is drawn from a ‘fact sheet’ written by an unnamed author for “Aboriginal Heritage Tasmania”, a Division of the Tasmanian Government’s Department of Primary Industries, Parks,Water and Environment:

“Wybalenna is one of the most significant Aboriginal historical places in Tasmania. It is located on the west coast of Flinders Island, the largest island in the eastern part of Bass Strait. In response to the escalating conflict between Aboriginal people and colonists during the 1820s, the colonial authorities discussed options to remove the Aboriginal people from their lands.The activities of ‘roving parties’ in the 1820s, George Robinson’s so-called ‘friendly mission’ in 1829 – 1831, and the Black Line in 1830, led to an agreement – or, some say, a treaty – between Aboriginal clan leaders and Governor Arthur in October 1831.The agreement led to the progressive removal of Aboriginal people from mainland Tasmania from 1831 to 1835.

After trialling several sites to house the removed Aboriginal people Commandant W J Darling settled on the current site on Flinders Island in February 1833. It was named ‘Wybalenna’. This was chosen as it meant ‘Black man’s houses’ in the language of the Ben Lomond people, the largest Aboriginal nation at the site.

In 1833, there were 57 Aboriginal people and 50 colonists at Wybalenna. From 1832 to 1835 about a dozen children were removed from Wybalenna to attend the Orphan School in Hobart. George Robinson became Commandant of the settlement in October 1835 and the Aboriginal people who had travelled with him since 1830, including Trukanini and Wurati, arrived at Wybalenna at this time. Several Aboriginal people from New South Wales and South Australia were also at Wybalenna for a time.

Schooling at Wybalenna began in 1834.The teachings included reading and writing in English, with a select group of Aboriginal children as the teachers – usually children of the clan leaders. As well as the weekday schools a Saturday evening school began in 1836. Male clan leaders spoke in their first language to their own clan, then to all Aboriginal people in the ‘pidgin’ ‘language of the settlement’. The school and chapel were located in one of the huts belonging to the Ben Lomond clan until July 1838 when the brick chapel was built. Sunday church services were announced with the ringing of a bell and raising the Union Jack. Attendance was not compulsory and less than one third of Aboriginal people attended.

In September 1836, two young men aged about 15,Walter Arthur (Ben Lomond) and Thomas Bruny (an orphan), began writing the ‘Aboriginal or Flinders Island Chronicle’. In the beginning, Robinson supervised their writing very closely but gradually the writers gained more independence. This is the earliest known newspaper written by Aboriginal people in Australia.

Following the departure of George Robinson to Port Philip (now Victoria) in February 1839, there was a dramatic reduction in resources provided to the Settlement. Most of the convicts and soldiers were removed. Doctor Jeanneret was appointed Commandant in 1842. Children were again removed to the Orphan School against their parents’ wishes. In February 1846, Walter Arthur and other Aboriginal people petitioned Queen Victoria to prevent Jeanneret returning. In spite of the petition, Jeanneret was reinstated. Conflict escalated and in 1847, Governor Denison ordered the closure of Wybalenna. By the time the settlement closed in 1847, approximately 130 people had died at Wybalenna. On 18 October 1847, the remaining 14 men, 23 women and 10 children were removed from Wybalenna and taken to the former convict station at putalina / Oyster Cove”.

Of the chapel itself, there is little information about it or contemporary accounts of its use. Indeed, the only substantial account of a religious service at Wybalenna dates to 1836, prior to the construction of the brick chapel in 1838. It is hard to assess the accuracy of the report published in the Hobart Town Courier, which has the appearance of propaganda piece in that it presented life at the settlement as idyllic:

“A temporary structure has also been put up as a church, and their voluntary attendance is we learn universal. Several have learned to join in the church music, in which they appear to take much delight. The observance of the sabbath, indeed, serves in that as in all other cases, as one of the best of all means, and better than any that man could devise, for the advancement of civilization. At day light on that day the Union Jack is hoisted at the mast head on the little mount that overlooks the village, which is taken as a signal to clean and prepare themselves in their best attire for the day of rest, and when the bell begins to toll to church they may be seen collecting round the church door”.

In stark contrast to this picture, Launceston’s Cornwall Chronicle published an astonishing and prescient view of the settlement which it called the Flinders Island Bastille:

“… [We] repeat our conviction of the positive necessity for an investigation into the management of it, and of every matter connected with it. Certain it is, that in a very short space of time three fourths of the Aboriginal Natives have died! If they are British subjects, their fellow subjects are privileged to be made acquainted with the cause of the extraordinary loss of life. It does not follow, that because these poor creatures have been forcibly transported to a desert island, they should die off like rotten sheep, without receiving even the common sympathy of their fellow men. It is true that they are of a different complexion to the invaders of their country; it is true, that being goaded on by cruelties to self defence, they sometimes retaliated upon their oppressors; and, perhaps, humane policy it was on the part of their oppressors, to remove them away from their native land. The policy of the measure, nevertheless, does not constitute it a just measure; the rightful inheritors of this land have been forcibly transported to a desert island, where, under the deceptive colour of humanity, they are forcibly detained— are forcibly subjected to a restraint and discipline, that will only terminate in their annihilation. What could Colonists have to fear from these poor, abused creatures, were they permitted to enjoy their native air in undisturbed freedom? Has our population of nearly 50,000 Englishmen, to fear injury from less than 100 harmless and unoffending natives, enjoying that liberty which is no less their right, than necessary for their existence? Away with such worse than childish fears. The net of detaining the rightful possessors of this land in captivity at Flinders' Island, is an act of political atrocity, that is disgraceful to ourselves and our country, and has but one parallel in the annals of civilized nations- that of Colonel Arthur inhumanly butchering, by the hands of the common hangman, some of this same race of native blacks”.

Upon settlement’s closure in 1847, Wybalenna’s brick chapel would have been in use for only 8 years. Like Tasmania’s ‘first people’, it has miraculously survived. After 1854, it was used as a barn and stood in a paddock, surrounded by a few grassy mounds, covering the remnants of the settlement’s ruined buildings. In 1970, ironically exactly 200 years after Captain Cook’s arrival, the National Trust of Australia, initiated steps to acquire and restore the Wybalenna Chapel. The owner of the building, Thomas Morton, agreed to swop the chapel in exchange for a new shearing shed.

During the 1970s and 1980s increased interest in the site, and the cemetery in particular, led to archaeological surveys and the making of the film, ‘Black Man’s Houses’. In late 1991 a small group of approximately ten Aborigines re-occupied the site and made it clear that they had reclaimed the area in the name of the Aborigines living on Flinders Island. This was clearly broadcast to the world with a sign hung on the gate which read: “You are now entering Aboriginal land, please respect our culture”.

In 1999 the Tasmanian Government, under the Aboriginal Lands Act (1995), returned the land to the Tasmanian Aboriginal community. The title of the land was vested with the Aboriginal Land Council of Tasmania and Wybalenna’s management and preservation is under the care of the Flinders Island Aboriginal Association Incorporated.

|

| The Chapel c.1999 - Libraries Tasmania LPIC 108-1-88 |

|

| Source: The Weekly Courier 1903 |

|

| Source: Libraries Tasmania (undated) PH30-1-1979 |

|

| A recent photo of the chapel - courtesy of Tasmania 360.com |

|

| The Wybalenna Settlement 1847 - J W Beattie - Libraries Tasmania |

Sources:

The Hobart Town Courier, Friday 25 March 1836, page 2

Cornwall Chronicle, Saturday 16 March 1839

Cornwall Chronicle, Saturday 9 June 1838

Cornwall Chronicle, Saturday 22 July 1837

Australian Women's Weekly, Wednesday 17 June 1970, page 40

https://www.aboriginalheritage.tas.gov.au/Documents/AHT%20Fact%20Sheet%20-%20Historical%20Places%20Wybalenna.pdf

https://www.utas.edu.au/library/companion_to_tasmanian_history/W/Wybalenna.htm

http://tacinc.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Wybalena_17.4.15.pdf

Comments

Post a Comment