No. 1143 - Port Arthur - Point Puer Chapel (1834-1849)

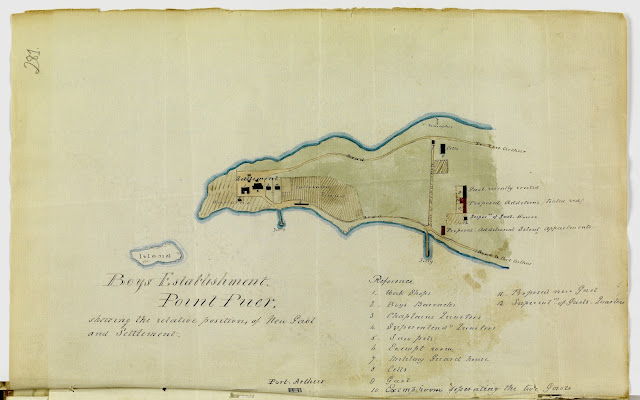

Point Puer, situated on a narrow peninsula directly east of Port Arthur, was the site of Australia’s first purpose-built reforming institution for criminal boys. Operating from 1834 to 1849, it was initiated by Lt-Governor Arthur with the aim of making constructive colonial citizens out of transported boys through education, trade training and religious instruction. The degree to which this was achieved is a matter for debate.

On 10 January 1834, 68 boys arrived at Point Puer along with supplies needed to establish the site. By the end of the decade 500 boys were living at Point Puer. Between 1842 and 1844 the numbers peaked at around 800. However, by the mid 1840s Point Puer was in rapid decline. The construction of the Parkhurst Reformatory on the Isle of Wight in 1838 resulted in fewer boys being transported to Australia. Point Puer closed in 1849 by which time about 3500 boys had passed through the institution. Most of the boys were aged between 15 and 17, a smaller number were under 15 and a very few were 12 and under.

This article’s focus is on the role of religion at Point Puer, which was an essential part of the process of rehabilitation. With adult convicts, religion was viewed as a critical tool in changing behaviour. A 2008 UNESCO report on convict sites in Australia notes that this was achieved through:

“…The construction of churches and chapels for the use of convicts; employment of chaplains at penal stations responsible for the moral improvement of convicts; compulsory attendance at church services; reading of prayers by authorities and ‘private masters’ and distribution of Bibles. Separate churches or rooms were often provided for convicts from different religious denominations. Religious observances were often an essential part of the daily lives of most convicts including those under going secondary punishment. Attendance was rigidly enforced and non-attendance was a punishable offence…”.

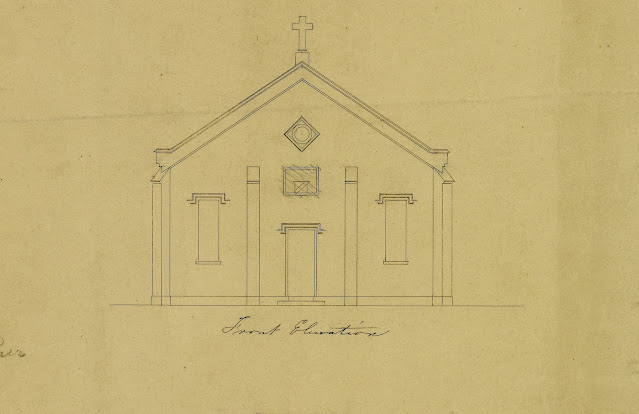

Religious instruction and worship at Point Puer followed the same lines as adult prisons. In 1837 a design for a chapel was commissioned but this was never built. Instead, the boys’ barracks doubled as a place of worship as well as a school room. Instead of beds the barracks had hammocks which were removed in the daytime. In practice many of the boys slept on the floor.

A typical 7½ hour working day began at 5 in the morning and would be taken up with general labour, trade training, school work and religious devotions, including prayers, which began and ended the day. The daily routine was divided into four main areas: education; moral and religious training; labour and trade training, and discipline.

In 1837 a report on Point Puer, written by Captain Charles O’Hara Booth, Commandant of the Port Arthur Penal Settlement, provides some insight about the boys’ religious regime.

“On Sunday the boys rise as usual, attend morning prayers and at nine o’clock a clean shirt and soap is issued to them for the week; at half past ten they are mustered for Divine Service which is held in the Barracks, Dinner at one. School from half past two until half past four, Supper at five, and Divine Service in the evening at six, which is performed by the Superintendent officiating as Catechist (occasionally by the Wesley Minister attached to Port Arthur). The prayers read are those of the established Church of England and on each occasion an approved Sermon adapted to the comprehension of the congregation is delivered, at the close of which the boys are catechised on the subject of discourse. It affords me pleasure to observe from the answers given that considerable degree of attention to the subject must have been paid, tho’ the voluntary answers given appear to be confined to a few only and those generally by such as more devoutly disposed”.

While the proposed chapel was never built a small gaol on the site was converted for religious services and classes for exclusive use by Roman Catholic boys. Financial records from the last year of Point Puer’s operation reveal that the Catechist received an annual payment of £150 while the ‘Roman Catholic Catechist received a lesser amount of £80.

As with other convict prisons there is clear evidence of religious factionalism at Port Puer. In ‘Planting a Faith in Tasmania’, Terry Southerwood describes an incident that took place in June 1844:

“Trouble was brewing at Point Puer when the catechist O’Halloran forbade a Catholic boy to “join in chanting the grace before dinner”, a task he had performed for three years. O’Halloran was castigated by the Comptroller for “departing from established regulation and practice”. Such a course by a religious instructor could not “but be productive of injurious results, as it furnishes the convict with a ground for disobeying the orders of those entrusted with their immediate control and discipline”. At this stage there were 188 Catholic boys at the Point Puer Boys’ Probation Party”.

Southerwood goes on to describe another incident that involved Catholic Bishop Robert Willson:

“Always on the lookout for discrimination, Bishop Willson protested that a Catholic boy at Point Puer (Christopher Bentley) was being bought up as a Protestant. Father Bond, the chaplain, examined Christopher and reported: “I have not the slightest doubt that the poor little fellow is, and always was, a Catholic”. The Lieutenant Governor directed that the boy “should continue to attend the Protestant Church”. Unwilling to give up the fight on this principle of religious liberty, the prelate eventually won the day when Christopher Bentley was “entered in the record as a Roman catholic” and began “receiving religious instruction accordingly”.

While the historical record of the practice of religion at Point Puer is not extensive, it is nevertheless an important link in the colonial penal system and mirrors practises at prisons, ‘female factories’ and probation stations across the colony.

Sources:

On 10 January 1834, 68 boys arrived at Point Puer along with supplies needed to establish the site. By the end of the decade 500 boys were living at Point Puer. Between 1842 and 1844 the numbers peaked at around 800. However, by the mid 1840s Point Puer was in rapid decline. The construction of the Parkhurst Reformatory on the Isle of Wight in 1838 resulted in fewer boys being transported to Australia. Point Puer closed in 1849 by which time about 3500 boys had passed through the institution. Most of the boys were aged between 15 and 17, a smaller number were under 15 and a very few were 12 and under.

This article’s focus is on the role of religion at Point Puer, which was an essential part of the process of rehabilitation. With adult convicts, religion was viewed as a critical tool in changing behaviour. A 2008 UNESCO report on convict sites in Australia notes that this was achieved through:

“…The construction of churches and chapels for the use of convicts; employment of chaplains at penal stations responsible for the moral improvement of convicts; compulsory attendance at church services; reading of prayers by authorities and ‘private masters’ and distribution of Bibles. Separate churches or rooms were often provided for convicts from different religious denominations. Religious observances were often an essential part of the daily lives of most convicts including those under going secondary punishment. Attendance was rigidly enforced and non-attendance was a punishable offence…”.

Religious instruction and worship at Point Puer followed the same lines as adult prisons. In 1837 a design for a chapel was commissioned but this was never built. Instead, the boys’ barracks doubled as a place of worship as well as a school room. Instead of beds the barracks had hammocks which were removed in the daytime. In practice many of the boys slept on the floor.

A typical 7½ hour working day began at 5 in the morning and would be taken up with general labour, trade training, school work and religious devotions, including prayers, which began and ended the day. The daily routine was divided into four main areas: education; moral and religious training; labour and trade training, and discipline.

In 1837 a report on Point Puer, written by Captain Charles O’Hara Booth, Commandant of the Port Arthur Penal Settlement, provides some insight about the boys’ religious regime.

“On Sunday the boys rise as usual, attend morning prayers and at nine o’clock a clean shirt and soap is issued to them for the week; at half past ten they are mustered for Divine Service which is held in the Barracks, Dinner at one. School from half past two until half past four, Supper at five, and Divine Service in the evening at six, which is performed by the Superintendent officiating as Catechist (occasionally by the Wesley Minister attached to Port Arthur). The prayers read are those of the established Church of England and on each occasion an approved Sermon adapted to the comprehension of the congregation is delivered, at the close of which the boys are catechised on the subject of discourse. It affords me pleasure to observe from the answers given that considerable degree of attention to the subject must have been paid, tho’ the voluntary answers given appear to be confined to a few only and those generally by such as more devoutly disposed”.

While the proposed chapel was never built a small gaol on the site was converted for religious services and classes for exclusive use by Roman Catholic boys. Financial records from the last year of Point Puer’s operation reveal that the Catechist received an annual payment of £150 while the ‘Roman Catholic Catechist received a lesser amount of £80.

As with other convict prisons there is clear evidence of religious factionalism at Port Puer. In ‘Planting a Faith in Tasmania’, Terry Southerwood describes an incident that took place in June 1844:

“Trouble was brewing at Point Puer when the catechist O’Halloran forbade a Catholic boy to “join in chanting the grace before dinner”, a task he had performed for three years. O’Halloran was castigated by the Comptroller for “departing from established regulation and practice”. Such a course by a religious instructor could not “but be productive of injurious results, as it furnishes the convict with a ground for disobeying the orders of those entrusted with their immediate control and discipline”. At this stage there were 188 Catholic boys at the Point Puer Boys’ Probation Party”.

Southerwood goes on to describe another incident that involved Catholic Bishop Robert Willson:

“Always on the lookout for discrimination, Bishop Willson protested that a Catholic boy at Point Puer (Christopher Bentley) was being bought up as a Protestant. Father Bond, the chaplain, examined Christopher and reported: “I have not the slightest doubt that the poor little fellow is, and always was, a Catholic”. The Lieutenant Governor directed that the boy “should continue to attend the Protestant Church”. Unwilling to give up the fight on this principle of religious liberty, the prelate eventually won the day when Christopher Bentley was “entered in the record as a Roman catholic” and began “receiving religious instruction accordingly”.

While the historical record of the practice of religion at Point Puer is not extensive, it is nevertheless an important link in the colonial penal system and mirrors practises at prisons, ‘female factories’ and probation stations across the colony.

| |

|

|

| Aerial view of Point Puer with the Isle of the Dead in the foreground (Libraries Tasmania) |

|

|

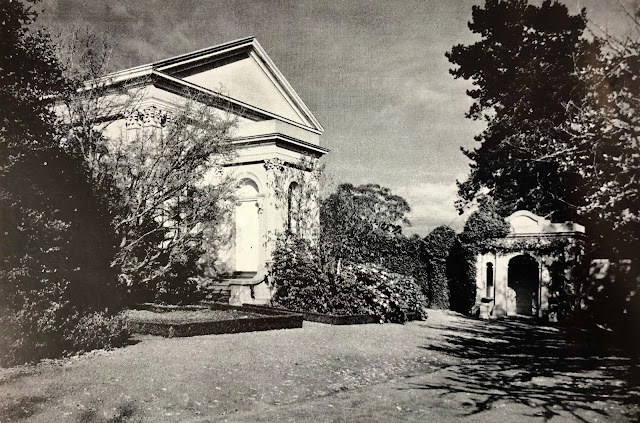

Elevation and section of the Boys Barracks, on Point Puer (Courtesy of the Tasmanian State Archives) |

|

| Map of Point Puer, circa 1840 (Tasmanian State Archives CSO5/36/752 ) |

Peter H. PacFie, Robin McLachlan & Malcolm H. Mathias; Point Puer Lads: Tried and Transported

The Point Puer Lads and Their Prison; 1833-1849; Published by the

State Computer Education Centre Genoa Street MOORABBIN Victoria 3189, 1987

Brand, Ian; The Convict Probation System, Van Diemen's Land 1839-1854, Sandy Bay, 1990,

Burn, David and Beattie, J. W. (John Watt), 1859-1930 An excursion to Port Arthur in 1842. 'The Examiner' and 'Weekly Courier' offices, Launceston, Tasmania, 1910.

Southerwood, W. T Planting a faith in Tasmania. Southerwood, Hobart, 1970.

Australia. Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts. Australian convict sites : world heritage nomination / Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts Dept. of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts Canberra 2008 <http://www.environment.gov.au/heritage/publications/about/pubs/convict-sites.pdf>

Booth’s Report, dated July 24, 1837, to the Colonial Secretary in Volume 3, British Parliamentary Papers on Transportation.

https://www.findandconnect.gov.au/ref/tas/biogs/TE00236b.htm

https://www.utas.edu.au/library/companion_to_tasmanian_history/P/Point%20Puer.htm

Comments

Post a Comment