No. 1299 - Latrobe - Gilbert Street Barracks - "Salvation Army Joe"

Latrobe is a large country town on the east bank of the River Mersey. The settlement was named after Charles LaTrobe, who was acting Lieutenant-Governor of Tasmania in 1846-7. Until the River Mersey silted up Latrobe was once an important port town.

The Salvation Army has an historical link with Tasmania. While living in London in the 1870s, Launceston businessman and philanthropist, Henry Reed, donated £5000 to William Booth to help the Salvation Army establish a firm financial foundation for its work. In 1883 the Salvation Army was established at Launceston and ‘Army’ corps were soon after formed at Hobart, Latrobe, Waratah and at other towns.

The Salvation Army arrived at Latrobe in late 1883 and remained active in the town until 1917. Thereafter it functioned intermittently with the Salvation Army Hall or “barracks” briefly reopening in 1919 and again in 1930. The ‘Army’s’ first premises were in an old factory building and later a hall or ‘barracks’ was established on Gilbert Street.

The Salvation Army’s arrival at Latrobe was no less controversial than it was in other Tasmanian towns. The public reception to the ‘Army’ was initially hostile and establishment churches and the middle-class were wary of its noisy and disruptive proselytising on the streets. The raucous nature of the ‘Army’s’ open-air gatherings and street processions tended to attract the working classes and people on the fringes of society. In Launceston and Hobart, processions were shadowed by a ‘skeleton army’ that parodied its marches and disrupted its meetings; sometimes violently. In Hobart the leader of the ‘Army’, Captain Gallagher, as well as others, were imprisoned for breaching municipal by-laws but were released after the intervention of the Attorney General. At Latrobe the targeting of Salvation Army gatherings by the ‘larrikin element’ was a significant feature of the early years.

The Salvation Army’s arrival at Latrobe was reported by the Devon Herald in December 1883:

“…An excitable member of the Army has arrived, and he obtains no audience but a mob of larrikins who assemble to jeer and laugh at his absurd and eccentric manner. The Wesleyan School-room was allowed for his services, and the meeting became so disorderly that he was refused admission since Thursday night last….”.

Some Latrobe residents were appalled by these events as well as the absence of the police when matters got out of hand. In December 1883, a witness to the events, wrote a letter of complaint to Launceston’s Daily Telegraph:

“We have had a visit from one of the members here, and l am sorry to say that he is treated very unkindly by the youths of this district. It is a great shame that the police do not protect him and put a stop to his being treated in an unhuman manner. They are not satisfied by scoffing at him, but they go so far as to stick pins in him, push a great crowd on him, and knock him down. If it had not been for the kindness of the Rev. Mr Bennett and Mr Hainsworth I believe they would have roughly handled him. Now, sir, we all pay police rates, and what do we pay them for?”

In January 1884 another Latrobe resident, using the pseudonym “Subscriber”, wrote to the Daily Telegraph complaining that converts to the ‘Army’ were also targets of the ‘larrikins’:

“I am sorry to say there was one young man converted in the Army, and it appears some people got him into an hotel in the centre of our township and actually got the poor creature down and poured the intoxicating drink down his throat, then dipped his head in a cask of water, and [had] him pleading for mercy. Then they threw flour over him after 10 o’clock at night, also took his colours off him and made away with them, and what makes the case worse is that the victim is not altogether right in his intellect…..”.

It was not long before a “Skeleton Army” emerged at Latrobe. In April 1884 the Devon Herald reported:

“Larrikinism, which in the past at Latrobe generally presented itself in the shape of removing shutters, knocking at doors, ringing of doorbells, whitewashing premises boards, poisoning of dogs, mutilating sign-boards, fastening cords across the roads, fixing logs across the footpaths, molesting respectable females at street corners, using obscene language, ill-using dumb animals, tearing down fences, robbing orchards, etc., etc., has now developed in quite a new direction, viz., interfering with the Salvation Army, under the banner of what they call the Skeleton Army. These latter interesting individuals have taken some little trouble to manufacture a red banner, on which an attempt has been made to give the idea of a skull and cross-bones, and red bands have been procured for their hats. In this guise a mob of them try nightly with all their power to put down with hard shouting the proceedings of the Salvation Army, by walking close in front front of the procession, gesticulating in a frenzied manner, and singing at the top of their very unmusical voices. Although we do not agree with the Salvation Army’s ideas of religious observance, we find them a very harmless band of individuals, who do not directly interfere with any other body, or with any particular individuals; and against such senseless idiots as the Skeletons we think they should in some way be protected”.

The article continued and also suggested that the larrikins may not be Latrobe locals:

“For some time past they have interfered with the Salvationists, and sometimes succeeded in quite drowning their voices, but on Wednesday night the disorderly vagabonds went a step farther, and stopped the progress of the meeting at the "barracks." The army men… did not, of course, know how to deal with them, so had to close the meeting. We are informed—but cannot vouch for the truth of the statement — that the police were sent for, but would not attend the summons…. Since the occasion…Captain Buick has, we understand caused summonses to be issued to call the ring-leaders in the disturbance to account, and we hope he will succeed in setting a conviction…. In concluding, we feel bound to remark that not only at the present time, but for years past, the larrikinism perpetrated here has been, almost invariably, the work of strangers, or rather road-men and others who have been employed in and around the town on Government contracts. Our local youths and young men who are permanently resident in the town are, with a few exceptions, above such malicious acts as those perpetrated here from time to time…and we think they are of too manly a disposition to be found mixed up in such eminently childish and senseless pastimes. We find that the Skeleton Army is composed of persons new to our town, and we do not think a local face can be found in their ranks. It is generally understood that when road work, or any kind of extensive Government contract is being carried out near us, we look for exhibitions of larrikinism, and at other times we seldom hear of a case being proven. We hope “our boys" will hold themselves aloof from any suspicion of larrikinism, and also keep clear of such a class of individuals as those composing the Skeleton Army".

The Salvation Army also experienced opposition from the owners of Latrobe’s hotels and other purveyors of alcohol. In December 1884 the owners of the Club Hotel, the Latrobe Hotel and the Royal Hotel accused the Salvation Army of disturbing the peace and of threatening behaviour. The case was brought before the Latrobe Police Court. The Hobart Mercury reported:

“The courthouse was crowded this morning to hear the trial of Capt. Hatcher, Lieut. Tyler, Happy Charley, George Sellars, Joseph Butler, William Lawler, William Richards, Sarah Marshall, John Cook, and Mrs, Butler, members of the Salvation Army, for disturbing the peace …The evidence of Robert Earl, George Barber, Joseph Bramich, and others, showed that the accused stood opposite public houses and sung a hymn to the effect that they would make barracks of the houses, captains of the landlords, and Salvation lasses of the barmaids. The accused were all found guilty, with the exception of Richards, who was discharged with a caution. The women were also discharged with a caution, and Hatcher, Tyler, Sellars, Butler, and Lawler were fined £1 each and costs, or seven days' hard labour in prison. Hatcher and Tyler decided to take the imprisonment, but the rest paid their fines”.

Captain Hatcher and Lieutenant Tyler’s imprisonment was to provide both sympathy and propaganda for the Salvation Army's cause across Tasmania. In late December 1884, the experiences of the jailed men, were recounted at a recruitment meeting held at Launceston. The speaker was mocked in the Examiner’s report of the meeting:

“A great feature was the sensational description given by members of the army who were recently fined at Latrobe for disturbing the public peace. "Captain" Hatcher and "Lieutenant" Tyler, otherwise “Happy Charley," preferred "taking it out" in gaol for a week to paying the fine, and the account given by the latter of the whole proceedings was certainly amusing if not strictly accurate. According to his version, nine soldiers were summoned "before the bar of justice for obstructing ‘pore sinners from goin’ to ‘ell’, and the witnesses against the “prisoners” were five publicans, but “the devil was also there in full form" and what the witnesses, who swore to 'the foulest lies,' were "afraid to say, the Superintendent of Police put into their mouths, and what he didn't say the clerk he wrote down with his pen”. Charley has had considerable experience of courts and witness’s, etc., but professed himself staggered with the proceedings of the Latrobe Police Court. After spending one night in the Latrobe lock-up in a “nine by four” cell, the “captain” and Charley - because they had too many dear friends in Latrobe - were marched by a “Christian. policeman” seven miles to “the new gaol” at Torquay, and though “the captain,” never having been inside of a cell before; felt rather low spirited, Charley was all at home, and did his best to make them both comfortable”.

The incident marked a low point for the Salvation Army at Latrobe but while the ‘Army’ continued to be harassed, it gradually became to be accepted. In 1888 the barracks moved from the back streets of Latrobe to a more central position on Gilbert Street.

A lot more could be written about the Salvation Army’s early years at Latrobe but I will end with an a retrospective article from The Advocate, penned in 1928, by its regular correspondent, “The Wild Irishman” who reflected on the passing of “Salvation Army Joe”:

“When that splendid and useful organisation, the Salvation Army, first came to Tasmania, their welcome was not a very warm one….Many, years ago, when the Army was having a great battle for existence at Latrobe, there arrived a fine…strapping wearer of the neat red and blue uniform in the person of “Salvation Army Joe,” or “Captain Joe,” as some called him. Anyhow, many of the “old hands” of the town used to take a look over Joe (like looking at a bullock in the auction ring), and say, “He is big enough to be on the pick and shovel; he ought to be at work”. Well, as it happened, Joe proved that he was a glutton for work in a great many ways, and in a very short space of time he was beloved by the whole town. Joe didn't only do his duty to the Army; he did more than that,… and in the humble opinion of "The Wild Irishman," the minister of religion who only “does his duty” is a very poor representative of the poor, humble Galilean.

"Duty" in many cases nowadays means a good easy-job at a real good pay. Therefore, I say that when a man throws off the shackles of duty and goes "flat-out" to help his poorer or more unfortunate brothers, as Joe did, he is one of God's good men. During my journey through life I have met these men sometimes in the dress of clergymen, and sometimes carrying their swags; and big-hearted men have often been reduced to the latter occupation.

Well, Joe used lo lead his little band along Gilbert street until he arrived in front of Young's Railway Hotel, and there he would endeavour to show us old and young sinners the road to take through life. I can now in my mind's eye see poor "Salvation Joe" standing there in the rain, with his hand pointing this way and that, but as sure as the sun rises, poor Joe's hand, whether it pointed north, south, east or west, was pointing to Heaven…..On one occasion a huge man full of sin and beer walked over to the ring, and sought to engage Joe in fight; but Joe, who had been a noted boxer in Collingwood, Melbourne, had fought his last ring battle, and in a very few minutes by his kind and persuasive manner, he had the poor old sinner kneeling in the ring. On another occasion a poor widow woman had her house burned to the ground three miles and a half from Latrobe. It was only a humble cot., but it was the home of her five orphans. Joe didn’t stop to find out what her religion was, but one night he called on the good people of the town to provide wood for the house and bricks for the chimney, saying that he would rebuild the widow's cot. as his part of the performance; and, God rest him, so he did. For three months he walked the distance morning and night, and he was as pleased as a little boy with a packet of crackers when the job was finished. Joe didn't want any praise; he was hoarding up his treasures in a better land than this.

Well, as often is the case, when Latrobe could ill-afford to lose him, the Army captain was shifted to another part of Tasmania, Mount Zeehan, as it was known in those days. The typhoid fever was rampant there then and, of course, Joe worked hard and long amongst the sick until at last, completely worn out, his once splendid and healthy body fell a victim to the dread disease, and on one wet and windy morning the miners, bare-headed, in the pouring rain, laid him to rest. There is not the least doubt that poor Joe's spirit had found that heaven to which his hand had pointed in front of the old pub at Latrobe….”.

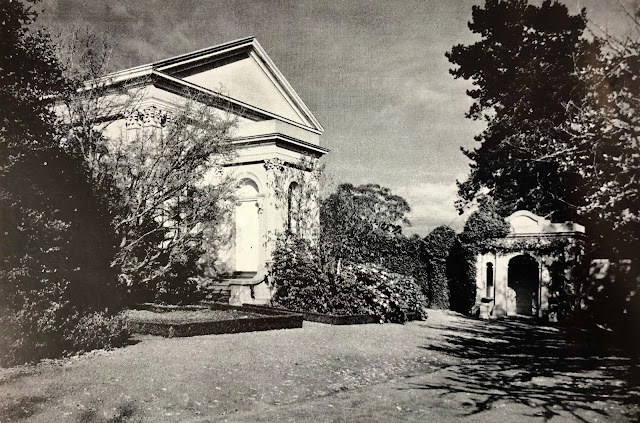

Latrobe's old Salvation army Barracks on Gilbert Street. The building was later used by the Church of Christ: source: Libraries Tasmania

The Salvation Army barracks at Latrobe. source: The Salvation Army Museum, Melbourne.

Sources:

Devon Herald, Monday 24 December 1883, page 2

Daily Telegraph, Friday 28 December 1883, page 3

Daily Telegraph, Saturday 19 January 1884, page 3

Devon Herald, Tuesday 4 March 1884, page 2

Devon Herald, Saturday 19 April 1884, page 2

Daily Telegraph, Thursday 18 September 1884, page 3

Launceston Examiner, Thursday 25 September 1884, page 4

Daily Telegraph, Tuesday 16 December 1884, page 3

Devon Herald, Tuesday 16 December 1884, page 2

Mercury, Tuesday 16 December 1884, page 3

Launceston Examiner, Saturday 27 December 1884, page 3

Launceston Examiner, Monday 29 December 1884, page 3

Daily Telegraph, Friday 29 May 1885, page 3

Devon Herald, Tuesday 14 February 1888, page 2

Advocate, Monday 15 September 1924, page 7

Advocate, Thursday 6 December 1928, page 11

Advocate, Saturday 7 January 1933, page 5

Comments

Post a Comment