No. 1430 - Launceston - Cameron Street "Joss House" (1872)

This is one of a series of articles that explores Tasmanian places of worship other than Christian churches. These buildings include mosques; synagogues; temples and gurdwaras. At least five religious denominations have established purpose-built places of worship in the Tasmania.

A “Joss House” (or more correctly, a Guan Di Temple), was a term used to describe a Chinese temple or shrine which typically includes altars, statues, incense and other religious artefacts. The term "joss" is derived from the Portuguese word "deus", meaning God. In 19th century Tasmania Joss Houses were established at mining settlements with significant Chinese populations such as at Weldborough, Garibaldi; Lefroy and Beaconsfield.

Until the 1870s Tasmania’s Chinese population was negligible. In the early 1870s a small number of Chinese miners arrived to work on the gold fields at Mathinna and elsewhere. In the mid 1870s the discovery of tin fields in the North East led to the arrival of a larger number of Chinese miners who mostly participated in the small-scale alluvial mining industry. While many European miners left the tin fields in response to the fall in tin prices in 1880s, Chinese miners continued to make a living from abandoned workings. The 1881 census counted 874 Chinese living in Tasmania, nearly all being tin miners. Over the next ten years numbers fluctuated around 1000, being about one percent of the colony’s population. With the passage of the Federal Immigration Restriction Act (1901), the number of new Chinese arrivals were severely restricted.

In 1872 the first ‘Joss House’ in Tasmania was established on the premises of Barnard and Peters located between Paterson and Cameron Streets. The company was involved in ‘securing the services’ of Chinese miners for the Tasmanian gold fields. Barnard and Peters was established in 1865 as importers and commission agents. When Barnard, Peters and Co. declared bankruptcy in October 1874 the Joss house became a victim of the business’s failure.

While the Cameron Street Joss House was short lived, it is notable for being the first place of worship established by Chinese migrants. The Joss House and its religious rituals were described in some detail in a number of Tasmanian newspapers. Extracts of these are reproduced as follows:

The first report appears in the Cornwall Chronicle. This was reproduced in several Tasmanian publications. The report describes the opening of the Joss House on Monday 12 August 1872.

“The first Joss-house or Chinese place of worship in this colony, was formally consecrated at midnight on Monday. This new ecclesiastical establishment has been the work of a few devotees, who remembered, in the land of the barbarians, the sacred truths they had been taught in their youth in their own celestial land. The new Joss-house has been constructed by the Chinese allowed to lodge in quarters at the stores of Messrs. Peters, Barnard, and Co., Cameron-street. It is a piece of furniture about the size of an ordinary chiffonier with upper cupboard. The lower part and the sides of the upper part have been covered with crimson cloth and overlaid with gold tinsel, and floral decorations. In the centre of the upper part is the full length likeness of “a welly good man, who live thousand years ago and more”. He ascended to heaven, and his son sits at his left hand to assist him in blessing all the Chinese people. On the right hand of the deity or “welly good man” stands a bearded piratical looking character, said to be a disciple of the “welly good man” but if so he looks more like a Judas disciple than an honest follower. In front are cunningly devised Joss-sticks, which when lighted filled the air with sweet incense. Oranges and other fruit and offerings were placed in front of the representation of the “welly good man,” and the greater part of Monday afternoon and evening were taken up in roasting a fine large porker in another part of the Chinese quarter; ducks and other delicacies, with plenty of rice, cooked as only the Chinese have patience to cook it, were also prepared for a great feast in honour of the celebration of the ceremony, which continued probably all night. Numbers of Chinese visitors from the goldfields were present. The place was well lighted with wax candles in Chinese lanterns, manufactured by the makers of the Joss-house. One feature of the ceremony was the opening of the astrological Joss-sticks, which told wonderful things of the past, present, and future to all the devotees at the shrine of the “welly good man.” Yesterday morning the feasting, with discharge of Chinese crackers by way of royal salute to the “welly good man,” was very brisk ; but all was done quietly, systematically, and with a simple earnestness quite edifying. The headquarters of the Chinese is in the midst of large spirit stores, but their religious festivity passed off without the use of much of either spirits, wines, beers, or other intoxicating liquors. We understand the Chinese High Priest and his disciples intend to apply to the Government shortly for grant of a piece of land for a site for a grand Joss-house as big as a church.”

2. The Launceston Examiner’s (17 August) description of the opening of the Joss House presents a somewhat different and perhaps more sympathetic observation than that of the Cornwall Chronicle:

“We were on Monday, through the courtesy of James Peters, Esq., shown some preparations that had been made by the Chinese in one of the outbuildings of Messrs. Peters. Barnard, & Co.'s premises, for holding a religious festival that night, or more properly speaking, early next morning. We do not profess to be very deeply read in Chinese literature and, therefore, cannot say what was the occasion of this festival, but it appears that the chief idea was to do honour to somebody who came to China many years ago, and distinguished himself to such an extent that his memory has ever since been revered and worshipped — possibly it may be the renowned Confucius. On entering the shed the eye was at once attracted by a 'gorgeous display of gold tinsel and coloured papers around a table or altar. Immediately opposite the door and on a nearer approach a large picture stood on the altar, which was a representation of the illustrious individual, supported on either side by what might have been supposed to be an angel. Before this picture were placed a number of tapers, candles, sticks (which, when lighted, emitted a smell as of incense), a set of miniature basins, and a teapot, from which the idol was asked to drink brandy—a request, it is needless to say, he did not accede to. And one article not the least curious in the motley collection was a small tin canister in which were placed a number of pieces of wood, something after the form of skewers, each of which were labelled with different Chinese characters; and every man present at the celebration of the feast drew from the canister one of the skewers, and according to the inscription it bears knew whether he has acted in accordance with the wishes of the idol since the previous festival. On different parts of the shed inscriptions in the Chinese language were written, and Chinese lanterns, fly cages of the latter being really marvellous. We may state that although the Chinese met on this occasion for the purpose of ministering to the wants of their souls their bodies were not forgotten, as the proceedings terminated with a sumptuous repast, the principal feature of which was a pig roasted, and placed upon the table whole in a large trough made specially for the purpose”.

3. Another article was published in the Launceston Examiner on 26 September 1872. This provides an interesting description of rituals relating to rituals of divination:

“On Tuesday afternoon a grand festival was held by the Chinese at their Joss-house, at the stores of Messrs Peters, Barnard, and Co. Some diggers returned from Brandy Creek [Beaconsfield] on Monday night by the steamer Annie, bringing with them a parcel of gold valued at £26, included in which was one gold' nugget worth about 35s, the remainder being very fine and scaly; and although the expedition had been pronounced by John as “no welly good,” they decided to return thanks to their oracles for past favours, and solicit further indulgences. Accordingly, the "welly good man” and his associates - one being a remarkably savage-looking character - were set up on high, surrounded by the thousand and one cunningly devised ornaments and embellishments which the Chinese are so apt at manufacturing, such as fly-cages; lanterns; and numerous nondescript fantastically artistic shavings and cuttings in coloured and gilt papers. On a table in front of the fortunate object of adoration were placed three or four fine roasted fowls, pork, &c., with a plentiful supply of oranges, preserved ginger, nuts, and other items usually included in a dessert course, together with an unlimited quantity of pure and unadulterated brandy. Prior to the commencement of the service all the Celestials present - some 20 -were busily engaged in laughing and cracking jokes with each other; but on a sign from one (whom for the sake of convenience we will dub the priest) levity was cast aside, pigtail unfastened, and a semi-circle formed round the altar. The priest and the man, who on behalf of himself and party was about to consult the fates with reference to a proposed trip to the Hellyer, knelt very devoutly before the “welly good man,” took a miniature cup filled with brandy, sprinkled the contents before the altar, refilled it and placed it on the table. The legs, wings, head, and tail were then torn off one of the fowls by an attendant, who used his fingers pretty freely during the operation; placed in a basin, waved before the, altar and then placed on it. This was followed by a vast amount of bowing, scraping, genuflecting, and other vagaries on the part of the priest and the suppliant, assisted at certain intervals (as a play bill would say) by the whole strength of the company. During this performance the priest took two pieces of wood, which when joined formed a stick about a foot long, with a crook in the middle, and cast them on the ground. This process was repeated' many times. The priest in a very impressive manner muttered cabalistic jargon to his heart's content; the devotee who wanted “to know you know” drew forth a pastile out of a tin canister, handed it to an attendant, and the ceremony was then wound up by a gorgeous display of fireworks--packets each containing twelve dozen Chinese crackers being ignited simultaneously. Having thus settled the propitiatory dues of the "welly good man,” all turned their attention to finding out what advantage had accrued to themselves for their trouble, and flocked around a sachem who was busily engaged in ferreting out what the signs that had been shown portended. After poring over it for about five minutes with a very mysterious air, the sage announced that the expedition would not be very successful, as the gold would be difficult to get at. This news did not produce any visible effect, and the enterprise is not to be abandoned because the now “welly bad man”had thought fit to "cut up rough," although it will considerably damp the ardour of the party. The cook then proceeded very methodically to chop up the eatables that had stood on the altar with a tomahawk, preparatory to making dishes for a great feast to be held the same evening.

[Since writing the foregoing we have been informed that later in the evening the Chinese decided on giving up the excursion, in consequence of the adverse result of the appeal to the “welly good man.” But yesterday morning about one o'clock, there was a great commotion, when the Chinese arose from their beds and went through the whole affair again, thinking that possibly there might have been some errors and omissions in the previous ceremony. On this occasion the "welly good man” considered the petition more favourably, and gave the required answer, viz. that they would meet with abundant success. During yesterday there was considerable excitement at Messrs Peters, Barnard; and Co.'s yard,’where preparations were being made on a large scale for their departure, and they proceed this morning by the Pioneer to Table Cape en route for the Hellyer”.

While miners departed for Hellyer, the Joss House continued to be used. In October 1872 the Examiner reported:

“The Joss House is ever receiving additions, the last being a beautifully worked model of a Chinese ship or junk. The whole of the top part of which is of ivory, cut and carved in a most artistic manner….”.

For how long the Cameron Street “Joss House” functioned is not known. It was likely dismantled at some point in 1873 as the miners dispersed to various diggings and would not have survived Peter’s, Barnard and Company’s bankruptcy in 1874.

The last reference to the Cameron Street Joss House relates to a fire that broke out in 1881 at the former Peters, Barnard and Co. premises. The Launceston Examiner reported:

“Shortly before three o'clock yesterday be afternoon the Charles-street bell rang out an alarm of fire for the central-portion of the town, and the dense volumes of smoke at which were soon visible rising from the rear of the Public Buildings… It was, however, soon discovered that the fire had broken out in a former large wooden store, once the Chinese joss house, belonging to the property between Cameron and Patterson streets so long occupied by Peters and Co., afterwards by R. J. Sadler and Co., and purchased some seven months ago by Mr J. C. Genders, late of Adelaide,…The fire was discovered by Mr Genders, who smelling something burning, walked round the store and found it on fire in the rear, and at once gave the alarm….The store, which was an old weatherboard structure, as dry as tinder, was one mass of flames before the firemen reached the spot, and an adjoining shed, the iron roofed store, the roof of the large brick store, and the roof of the kitchen in the rear of the residence of the manager of the Bank of Tasmania were all on fire before long,… Mr Genders's premises are insured for close upon £1600 in the Mutual Company… The cause of the fire is not known, but a Chinaman who was formerly kept as caretaker of the premises, has been allowed by Mr Genders to live in the old store, and it is possible a spark from his fire may have is been the cause of the mischief….”

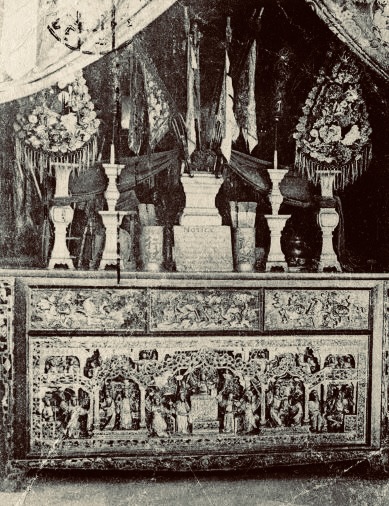

An example of a Guan Di Temple (Joss House) is on permanent display at Launceston’s Queen Victoria Art Gallery at Royal Park. This was relocated from Weldborough to the museum in the mid 1930s. It is possible that some ceremonial objects used in Cameron Street Joss House may have eventually found there way to Weldborough.

In an education programme produced for the ABC, Jon Addison, a curator at the Queen Victoria Museum, discussed the six ‘temples’ built in Tasmania’s North East in the 1880s:

“Chinese religion has a great tradition of largesse when you receive benefits and favour or good fortune. So the interesting thing is, most of the temples were built in one year, 1883. And that was the year when most people struck it rich. And as a result of this, people actually started to make a decent profit. They gave back and tried to encourage luck towards them by setting up and outfitting temples. And this involved actually spending in some cases really quite considerable amounts of money….As the tin mining declined gradually in northeast Tasmania, gradually some of these temples closed. And the best items from each one of these temples would get pooled together into another temple. And the more they closed, the more they got pooled together.

And all the material from these six temples ended up in one temple at Weldborough….Eventually they all ended up in Weldborough, under the control of the last temple custodian, who eventually decided to return to China. So in 1934, the contents of this temple were donated to the people of Launceston. And because the museum was a public space,…[a] separate room, was actually built to house the contents and to be a working temple for the Chinese population of Launceston at the time. And it's remained a working temple ever since….”.

Sources:

Helen Vivian, Tasmania's Chinese Heritage: An Historical Record of Chinese Sites in the North East Tasmania, Report Prepared for the Australian Heritage Commission, and the Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery, Launceston, 1985

https://www.abc.net.au/education/chinese-temples-in-19th-century-tasmania/13624928

A “Joss House” (or more correctly, a Guan Di Temple), was a term used to describe a Chinese temple or shrine which typically includes altars, statues, incense and other religious artefacts. The term "joss" is derived from the Portuguese word "deus", meaning God. In 19th century Tasmania Joss Houses were established at mining settlements with significant Chinese populations such as at Weldborough, Garibaldi; Lefroy and Beaconsfield.

Until the 1870s Tasmania’s Chinese population was negligible. In the early 1870s a small number of Chinese miners arrived to work on the gold fields at Mathinna and elsewhere. In the mid 1870s the discovery of tin fields in the North East led to the arrival of a larger number of Chinese miners who mostly participated in the small-scale alluvial mining industry. While many European miners left the tin fields in response to the fall in tin prices in 1880s, Chinese miners continued to make a living from abandoned workings. The 1881 census counted 874 Chinese living in Tasmania, nearly all being tin miners. Over the next ten years numbers fluctuated around 1000, being about one percent of the colony’s population. With the passage of the Federal Immigration Restriction Act (1901), the number of new Chinese arrivals were severely restricted.

In 1872 the first ‘Joss House’ in Tasmania was established on the premises of Barnard and Peters located between Paterson and Cameron Streets. The company was involved in ‘securing the services’ of Chinese miners for the Tasmanian gold fields. Barnard and Peters was established in 1865 as importers and commission agents. When Barnard, Peters and Co. declared bankruptcy in October 1874 the Joss house became a victim of the business’s failure.

While the Cameron Street Joss House was short lived, it is notable for being the first place of worship established by Chinese migrants. The Joss House and its religious rituals were described in some detail in a number of Tasmanian newspapers. Extracts of these are reproduced as follows:

The first report appears in the Cornwall Chronicle. This was reproduced in several Tasmanian publications. The report describes the opening of the Joss House on Monday 12 August 1872.

“The first Joss-house or Chinese place of worship in this colony, was formally consecrated at midnight on Monday. This new ecclesiastical establishment has been the work of a few devotees, who remembered, in the land of the barbarians, the sacred truths they had been taught in their youth in their own celestial land. The new Joss-house has been constructed by the Chinese allowed to lodge in quarters at the stores of Messrs. Peters, Barnard, and Co., Cameron-street. It is a piece of furniture about the size of an ordinary chiffonier with upper cupboard. The lower part and the sides of the upper part have been covered with crimson cloth and overlaid with gold tinsel, and floral decorations. In the centre of the upper part is the full length likeness of “a welly good man, who live thousand years ago and more”. He ascended to heaven, and his son sits at his left hand to assist him in blessing all the Chinese people. On the right hand of the deity or “welly good man” stands a bearded piratical looking character, said to be a disciple of the “welly good man” but if so he looks more like a Judas disciple than an honest follower. In front are cunningly devised Joss-sticks, which when lighted filled the air with sweet incense. Oranges and other fruit and offerings were placed in front of the representation of the “welly good man,” and the greater part of Monday afternoon and evening were taken up in roasting a fine large porker in another part of the Chinese quarter; ducks and other delicacies, with plenty of rice, cooked as only the Chinese have patience to cook it, were also prepared for a great feast in honour of the celebration of the ceremony, which continued probably all night. Numbers of Chinese visitors from the goldfields were present. The place was well lighted with wax candles in Chinese lanterns, manufactured by the makers of the Joss-house. One feature of the ceremony was the opening of the astrological Joss-sticks, which told wonderful things of the past, present, and future to all the devotees at the shrine of the “welly good man.” Yesterday morning the feasting, with discharge of Chinese crackers by way of royal salute to the “welly good man,” was very brisk ; but all was done quietly, systematically, and with a simple earnestness quite edifying. The headquarters of the Chinese is in the midst of large spirit stores, but their religious festivity passed off without the use of much of either spirits, wines, beers, or other intoxicating liquors. We understand the Chinese High Priest and his disciples intend to apply to the Government shortly for grant of a piece of land for a site for a grand Joss-house as big as a church.”

2. The Launceston Examiner’s (17 August) description of the opening of the Joss House presents a somewhat different and perhaps more sympathetic observation than that of the Cornwall Chronicle:

“We were on Monday, through the courtesy of James Peters, Esq., shown some preparations that had been made by the Chinese in one of the outbuildings of Messrs. Peters. Barnard, & Co.'s premises, for holding a religious festival that night, or more properly speaking, early next morning. We do not profess to be very deeply read in Chinese literature and, therefore, cannot say what was the occasion of this festival, but it appears that the chief idea was to do honour to somebody who came to China many years ago, and distinguished himself to such an extent that his memory has ever since been revered and worshipped — possibly it may be the renowned Confucius. On entering the shed the eye was at once attracted by a 'gorgeous display of gold tinsel and coloured papers around a table or altar. Immediately opposite the door and on a nearer approach a large picture stood on the altar, which was a representation of the illustrious individual, supported on either side by what might have been supposed to be an angel. Before this picture were placed a number of tapers, candles, sticks (which, when lighted, emitted a smell as of incense), a set of miniature basins, and a teapot, from which the idol was asked to drink brandy—a request, it is needless to say, he did not accede to. And one article not the least curious in the motley collection was a small tin canister in which were placed a number of pieces of wood, something after the form of skewers, each of which were labelled with different Chinese characters; and every man present at the celebration of the feast drew from the canister one of the skewers, and according to the inscription it bears knew whether he has acted in accordance with the wishes of the idol since the previous festival. On different parts of the shed inscriptions in the Chinese language were written, and Chinese lanterns, fly cages of the latter being really marvellous. We may state that although the Chinese met on this occasion for the purpose of ministering to the wants of their souls their bodies were not forgotten, as the proceedings terminated with a sumptuous repast, the principal feature of which was a pig roasted, and placed upon the table whole in a large trough made specially for the purpose”.

3. Another article was published in the Launceston Examiner on 26 September 1872. This provides an interesting description of rituals relating to rituals of divination:

“On Tuesday afternoon a grand festival was held by the Chinese at their Joss-house, at the stores of Messrs Peters, Barnard, and Co. Some diggers returned from Brandy Creek [Beaconsfield] on Monday night by the steamer Annie, bringing with them a parcel of gold valued at £26, included in which was one gold' nugget worth about 35s, the remainder being very fine and scaly; and although the expedition had been pronounced by John as “no welly good,” they decided to return thanks to their oracles for past favours, and solicit further indulgences. Accordingly, the "welly good man” and his associates - one being a remarkably savage-looking character - were set up on high, surrounded by the thousand and one cunningly devised ornaments and embellishments which the Chinese are so apt at manufacturing, such as fly-cages; lanterns; and numerous nondescript fantastically artistic shavings and cuttings in coloured and gilt papers. On a table in front of the fortunate object of adoration were placed three or four fine roasted fowls, pork, &c., with a plentiful supply of oranges, preserved ginger, nuts, and other items usually included in a dessert course, together with an unlimited quantity of pure and unadulterated brandy. Prior to the commencement of the service all the Celestials present - some 20 -were busily engaged in laughing and cracking jokes with each other; but on a sign from one (whom for the sake of convenience we will dub the priest) levity was cast aside, pigtail unfastened, and a semi-circle formed round the altar. The priest and the man, who on behalf of himself and party was about to consult the fates with reference to a proposed trip to the Hellyer, knelt very devoutly before the “welly good man,” took a miniature cup filled with brandy, sprinkled the contents before the altar, refilled it and placed it on the table. The legs, wings, head, and tail were then torn off one of the fowls by an attendant, who used his fingers pretty freely during the operation; placed in a basin, waved before the, altar and then placed on it. This was followed by a vast amount of bowing, scraping, genuflecting, and other vagaries on the part of the priest and the suppliant, assisted at certain intervals (as a play bill would say) by the whole strength of the company. During this performance the priest took two pieces of wood, which when joined formed a stick about a foot long, with a crook in the middle, and cast them on the ground. This process was repeated' many times. The priest in a very impressive manner muttered cabalistic jargon to his heart's content; the devotee who wanted “to know you know” drew forth a pastile out of a tin canister, handed it to an attendant, and the ceremony was then wound up by a gorgeous display of fireworks--packets each containing twelve dozen Chinese crackers being ignited simultaneously. Having thus settled the propitiatory dues of the "welly good man,” all turned their attention to finding out what advantage had accrued to themselves for their trouble, and flocked around a sachem who was busily engaged in ferreting out what the signs that had been shown portended. After poring over it for about five minutes with a very mysterious air, the sage announced that the expedition would not be very successful, as the gold would be difficult to get at. This news did not produce any visible effect, and the enterprise is not to be abandoned because the now “welly bad man”had thought fit to "cut up rough," although it will considerably damp the ardour of the party. The cook then proceeded very methodically to chop up the eatables that had stood on the altar with a tomahawk, preparatory to making dishes for a great feast to be held the same evening.

[Since writing the foregoing we have been informed that later in the evening the Chinese decided on giving up the excursion, in consequence of the adverse result of the appeal to the “welly good man.” But yesterday morning about one o'clock, there was a great commotion, when the Chinese arose from their beds and went through the whole affair again, thinking that possibly there might have been some errors and omissions in the previous ceremony. On this occasion the "welly good man” considered the petition more favourably, and gave the required answer, viz. that they would meet with abundant success. During yesterday there was considerable excitement at Messrs Peters, Barnard; and Co.'s yard,’where preparations were being made on a large scale for their departure, and they proceed this morning by the Pioneer to Table Cape en route for the Hellyer”.

While miners departed for Hellyer, the Joss House continued to be used. In October 1872 the Examiner reported:

“The Joss House is ever receiving additions, the last being a beautifully worked model of a Chinese ship or junk. The whole of the top part of which is of ivory, cut and carved in a most artistic manner….”.

For how long the Cameron Street “Joss House” functioned is not known. It was likely dismantled at some point in 1873 as the miners dispersed to various diggings and would not have survived Peter’s, Barnard and Company’s bankruptcy in 1874.

The last reference to the Cameron Street Joss House relates to a fire that broke out in 1881 at the former Peters, Barnard and Co. premises. The Launceston Examiner reported:

“Shortly before three o'clock yesterday be afternoon the Charles-street bell rang out an alarm of fire for the central-portion of the town, and the dense volumes of smoke at which were soon visible rising from the rear of the Public Buildings… It was, however, soon discovered that the fire had broken out in a former large wooden store, once the Chinese joss house, belonging to the property between Cameron and Patterson streets so long occupied by Peters and Co., afterwards by R. J. Sadler and Co., and purchased some seven months ago by Mr J. C. Genders, late of Adelaide,…The fire was discovered by Mr Genders, who smelling something burning, walked round the store and found it on fire in the rear, and at once gave the alarm….The store, which was an old weatherboard structure, as dry as tinder, was one mass of flames before the firemen reached the spot, and an adjoining shed, the iron roofed store, the roof of the large brick store, and the roof of the kitchen in the rear of the residence of the manager of the Bank of Tasmania were all on fire before long,… Mr Genders's premises are insured for close upon £1600 in the Mutual Company… The cause of the fire is not known, but a Chinaman who was formerly kept as caretaker of the premises, has been allowed by Mr Genders to live in the old store, and it is possible a spark from his fire may have is been the cause of the mischief….”

An example of a Guan Di Temple (Joss House) is on permanent display at Launceston’s Queen Victoria Art Gallery at Royal Park. This was relocated from Weldborough to the museum in the mid 1930s. It is possible that some ceremonial objects used in Cameron Street Joss House may have eventually found there way to Weldborough.

In an education programme produced for the ABC, Jon Addison, a curator at the Queen Victoria Museum, discussed the six ‘temples’ built in Tasmania’s North East in the 1880s:

“Chinese religion has a great tradition of largesse when you receive benefits and favour or good fortune. So the interesting thing is, most of the temples were built in one year, 1883. And that was the year when most people struck it rich. And as a result of this, people actually started to make a decent profit. They gave back and tried to encourage luck towards them by setting up and outfitting temples. And this involved actually spending in some cases really quite considerable amounts of money….As the tin mining declined gradually in northeast Tasmania, gradually some of these temples closed. And the best items from each one of these temples would get pooled together into another temple. And the more they closed, the more they got pooled together.

And all the material from these six temples ended up in one temple at Weldborough….Eventually they all ended up in Weldborough, under the control of the last temple custodian, who eventually decided to return to China. So in 1934, the contents of this temple were donated to the people of Launceston. And because the museum was a public space,…[a] separate room, was actually built to house the contents and to be a working temple for the Chinese population of Launceston at the time. And it's remained a working temple ever since….”.

|

| The former Weldborough Joss House now at the Queen Victoria Museum. Source: Pinterest |

|

| The Garibaldi Joss House (1914) - Source: Queen Victoria Museum - Object No. QVM:1983:P:1618 |

|

| Genders Lane, off Cameron Street, the approximate location of the shed which housed the Joss House. |

|

| Genders Lane off Cameron Street |

Sources:

The Cornwall Chronicle, Wednesday 14 August 1882, page 2

Mercury, Friday 16 August 1872, page 2

Tasmanian Tribune, Friday 16 August 1872, page 3

Weekly Examiner, Saturday 17 August 1872, page 10

Mercury, Friday 23 August 1872, page 3

Launceston Examiner, Thursday 26 September 1872, page 2

Cornwall Advertiser, Friday 27 September 1872, page 2

Launceston Examiner, Tuesday 8 October 1872, page 2

The Tasmanian Tribune, Monday 4 November 1872, page 3

Launceston Examiner, Tuesday 22 November 1881, page 3

Colonist, Saturday 16 November 1889, page 21

Examiner, Friday 2 July 1937, page 6

https://www.abc.net.au/education/chinese-temples-in-19th-century-tasmania/13624928

Thanks very much for this useful article. Could I check on one thing with you though? - there appears to have been a transcription error in when I am quoted as saying that most temples were built in 1893. The correct year that I would have said in the interview is actually 1883. It would be great to correct this in the text.

ReplyDeleteThanks for pointing out the error Jon. Your material was very helpful. I hope to follow up with articles about the other locations

Delete