No. 1568 - The Coal Mines Chapel (1833-1848)

The Coal Mines historic site one of 11 places listed as Australian convict World Heritage sites. The former convict precinct and mines are located on the northern promontory of the Tasman Peninsula adjacent to Little Norfolk Bay

The Coal Mines were established in 1833 as a punishment station for re-offending convicts and operated as an outstation of the Port Arthur penal settlement. In 1840 it was turned into a probation station based on coal mining. It was a severe place of punishment due to the dangerous conditions in the mines and punishment regime. At its peak the settlement had a population of almost 600 which included prisoners, soldiers, prison guards and their families. The mines closed in 1848 on economic and moral grounds.

In Tasmania’s penal institutions religious practice was, at least in theory, considered a critical part of reforming convicts. A 2008 a report for UNESCO notes that this was achieved through:

“…The construction of churches and chapels for the use of convicts; employment of chaplains at penal stations responsible for the moral improvement of convicts; compulsory attendance at church services; reading of prayers by authorities and ‘private masters’ and distribution of Bibles. Separate churches or rooms were often provided for convicts from different religious denominations. Religious observances were often an essential part of the daily lives of most convicts including those under going secondary punishment. Attendance was rigidly enforced and non-attendance was a punishable offence. Under the probation system, convicts were required to commence and end each day with prayers and attend two divine services on Sundays. Clergymen were critical cogs in the penal machinery, expected to be knowledgeable about the character of each convict. They were required to sign all key documents that could lead to the rehabilitation and freedom of individual convicts including applications for family members to be sent from Britain, tickets-of-leave, special privileges and pardons”.

At the Coal Mines the place of religion in the reform and moral development of convicts is emphasised by the location of the chapel and schoolroom at the centre of the convict compound.

In 1838 Commissariat Officer Thomas Lempriere described the Coal Mine convict precinct as a compound formed from three rectangular buildings surrounding a central square. A gated wall enclosed the one open side. In addition to the barracks and chapel, other stone buildings included a cookhouse, bakehouse and washhouse. Built on a slope, the east wing had a basement level, in which was placed a gaol, commissariat store and sixteen solitary cells. Other buildings in the immediate vicinity included a hospital, a catechists house and soldiers barracks.

In 1842 an imposing new stone Commissariat Store was constructed at the Plunkett Point Jetty. A new hospital and chapel, separate from the prisoners compound, was also planned. However these were never developed before the mines closed in 1848.

A pamphlet prepared for tourists and visitors visiting the site provides a little information about the chapel and schoolroom:

“The chapel lay in the centre of the settlement, reflecting the importance of religious instruction. Everyone had to attend chapel twice on Sundays,… [where] the men were so crowded together as to be almost unable to move. The chapel doubled as the schoolroom for the many children on the settlement, and for two evenings a week for two hours of compulsory instruction for the convicts. Many were not interested in learning; the medical officer said that often during school hours from want of proper surveillance, the books are torn up, even the bibles and prayer books, and packs of cards made of the leaves”.

Religious practice and instruction at the Coal Mines was provided by visiting Anglican, Catholic and Wesleyan clergymen and catechists. It is evident that religious instruction and worship was ineffective and even counterproductive. In 1847, the Anglican Bishop of Tasmania, Francis Russell Nixon, gave evidence before a House of Lords committee on the pitiable state of the convicts and the evils of transportation. Nixon agreed that a convicts “religious duties” were regarded as part of the sentence which contributed to antipathy towards Christianity:

“I must own myself, and it is a painful conviction to come to that with the best intentions, with the highest talents, and with the most assiduous work on the part of religious instructors, they are able to effect very little permanent good. I myself have preached often to convicts, and as often I have been struck with their very great attention during the time of Divine Service; apparently they have been struck with what has been said; but I could not conceal from myself, that immediately after Divine Service these men have gone back to their huts or to the mess-room, as the case may be; there they have been compelled to listen to conversation of the most depraved and profligate character; and if by God's grace a man's heart is a little touched by the delivery of Gospel truths, there is not one out of a thousand, or out of five thousand, who dares to exhibit any traces of penitence before his profligate companions. I may state, as I did in my report upon transportation, which I lately forwarded to Lord Grey, one other reason why so little good is done in the gangs by religious instructors, and it is an evil which stretches much further than during the time they are under bond, in all these gangs religious instruction is necessarily of a compulsory character; a man, for example, is compelled to attend the chapel twice on every Sunday; if he evades it or shirks it he is punished. Is it to be wondered at, that when the time of real or of comparative liberty comes, they should cast off attendance at the house of God with every other mark of their bondage? I believe I may truly say that all the clergy, although they may be able to tell of many instances of reformed characters amongst the convicts, lament the difficulty they have experienced of bringing these men to Church”.

While Nixon did not visit the Coal Mines, his views on the inadequacies of religious instruction are echoed in letters written by James Purslowe, a former superintendent of the Bridgewater, Jerusalem and Impression Bay Probation Stations and who was in charge of the Coal Mines between 1843 and 1844. In 1846 he wrote a letter to Lord Stanley (then British Secretary of State for War and the Colonies) in which he expressed his concerns with the probation system. In one letter, he described a bizarre and un-Christian-like practices at a religious services at the Coal Mines:

“At the Coal Mines there were about 600 men. A paid minister attended on Sundays only. In the morning he performed service for the prisoners, and in the evening for the visiting magistrate and his lady. This was the system here. The magistrate and his lady objected to attend prayers with the prisoners, and the minister who received £200 per annum, devoted himself every sabbath afternoon to the magistrates' family - the gang being left in idleness. When the Archdeacon visited, he administered the Sacrament; several prisoners expressed their desire to receive it, and their names were given in, but only free people were allowed to partake thereof. The magistrate and his lady upon this occasion desired to attend the morning service, and having a repugnance against entering the chapel by the same door as the prisoners, applied to the foreman of works to take out a window; to this I objected; the magistrate and lady consequently declined to attend the service; but after its conclusion, when the chapel was cleared, received the sacrament from the hands of the Archdeacon….”.

The Catholic catechist attending the Coal Mines was based at Port Arthur. In an incident in July 1846, he was attacked by two convicts from the Salt Water Probation Station after returning from giving religious instruction to Catholics at the Coal Mine chapel.

Two convicts, Michael Roach and John Dangan were subsequently charged with assault and robbery of Mr Roger Boyle, who was bludgeoned leaving a wound on the left side of his head. The two convicts, who were described as “mere boys”, were promptly tried. Roach, “who did not appear to be more than 20 years of age”, was executed “at the usual place” in front of the Hobart gaol. Dangan was transported for life to Norfolk Island.

In delivering the sentence at the Supreme Court, the judge observed that:

“The offence was one for which death would be awarded by the law under any circumstances, but there was one very dark feature of this robbery and dreadful assault. At the Port Arthur Coal Mines, and the Salt Water Station, the prisoners were of the worst and most depraved of even their own class. They stood in especial need of spiritual instruction that they might, in some degree at least, reclaim their lost diameters, and avoid those desperate courses in future which had placed them in their unhappy position. Here was a gentleman devoting his life for their good - travelling from the Coal Mines to the other station, in order to instruct them in their duty to God and man….It was an awful thing to reflect upon. The blow must have been given with great violence, and with the worst intentions.… That Mr. Hoyle was not killed upon the spot, could only be ascribed to the intervention of the Almighty providence of God…”.

While Roach was no martyr, it is somewhat ironic that he met his death with apparent Christian dignity. Reverend Hall, the Vicar General, who ministered to Roach and prepared him for his death noted:

“He was an intelligent young man, and had been better educated than most of the unfortunate men of his class. He conducted himself with considerable firmness, and died penitent.”

The Coal Mines were officially closed as a probation station in 1848 on 'moral and financial grounds', although the mines continued to be worked privately until 1877. The Coal Mines are significant because of their role in the anti-transportation debate. The colonial administration and Tasmanian opponents to transportation considered the place as among the worst penal stations for “unnatural crimes”. This was a factor contributing to the demise of the probation system, and was also used as a means of swaying British public opinion against the further transportation of convicts to Van Diemen's Land.

Sources:

The Coal Mines were established in 1833 as a punishment station for re-offending convicts and operated as an outstation of the Port Arthur penal settlement. In 1840 it was turned into a probation station based on coal mining. It was a severe place of punishment due to the dangerous conditions in the mines and punishment regime. At its peak the settlement had a population of almost 600 which included prisoners, soldiers, prison guards and their families. The mines closed in 1848 on economic and moral grounds.

In Tasmania’s penal institutions religious practice was, at least in theory, considered a critical part of reforming convicts. A 2008 a report for UNESCO notes that this was achieved through:

“…The construction of churches and chapels for the use of convicts; employment of chaplains at penal stations responsible for the moral improvement of convicts; compulsory attendance at church services; reading of prayers by authorities and ‘private masters’ and distribution of Bibles. Separate churches or rooms were often provided for convicts from different religious denominations. Religious observances were often an essential part of the daily lives of most convicts including those under going secondary punishment. Attendance was rigidly enforced and non-attendance was a punishable offence. Under the probation system, convicts were required to commence and end each day with prayers and attend two divine services on Sundays. Clergymen were critical cogs in the penal machinery, expected to be knowledgeable about the character of each convict. They were required to sign all key documents that could lead to the rehabilitation and freedom of individual convicts including applications for family members to be sent from Britain, tickets-of-leave, special privileges and pardons”.

At the Coal Mines the place of religion in the reform and moral development of convicts is emphasised by the location of the chapel and schoolroom at the centre of the convict compound.

In 1838 Commissariat Officer Thomas Lempriere described the Coal Mine convict precinct as a compound formed from three rectangular buildings surrounding a central square. A gated wall enclosed the one open side. In addition to the barracks and chapel, other stone buildings included a cookhouse, bakehouse and washhouse. Built on a slope, the east wing had a basement level, in which was placed a gaol, commissariat store and sixteen solitary cells. Other buildings in the immediate vicinity included a hospital, a catechists house and soldiers barracks.

In 1842 an imposing new stone Commissariat Store was constructed at the Plunkett Point Jetty. A new hospital and chapel, separate from the prisoners compound, was also planned. However these were never developed before the mines closed in 1848.

A pamphlet prepared for tourists and visitors visiting the site provides a little information about the chapel and schoolroom:

“The chapel lay in the centre of the settlement, reflecting the importance of religious instruction. Everyone had to attend chapel twice on Sundays,… [where] the men were so crowded together as to be almost unable to move. The chapel doubled as the schoolroom for the many children on the settlement, and for two evenings a week for two hours of compulsory instruction for the convicts. Many were not interested in learning; the medical officer said that often during school hours from want of proper surveillance, the books are torn up, even the bibles and prayer books, and packs of cards made of the leaves”.

Religious practice and instruction at the Coal Mines was provided by visiting Anglican, Catholic and Wesleyan clergymen and catechists. It is evident that religious instruction and worship was ineffective and even counterproductive. In 1847, the Anglican Bishop of Tasmania, Francis Russell Nixon, gave evidence before a House of Lords committee on the pitiable state of the convicts and the evils of transportation. Nixon agreed that a convicts “religious duties” were regarded as part of the sentence which contributed to antipathy towards Christianity:

“I must own myself, and it is a painful conviction to come to that with the best intentions, with the highest talents, and with the most assiduous work on the part of religious instructors, they are able to effect very little permanent good. I myself have preached often to convicts, and as often I have been struck with their very great attention during the time of Divine Service; apparently they have been struck with what has been said; but I could not conceal from myself, that immediately after Divine Service these men have gone back to their huts or to the mess-room, as the case may be; there they have been compelled to listen to conversation of the most depraved and profligate character; and if by God's grace a man's heart is a little touched by the delivery of Gospel truths, there is not one out of a thousand, or out of five thousand, who dares to exhibit any traces of penitence before his profligate companions. I may state, as I did in my report upon transportation, which I lately forwarded to Lord Grey, one other reason why so little good is done in the gangs by religious instructors, and it is an evil which stretches much further than during the time they are under bond, in all these gangs religious instruction is necessarily of a compulsory character; a man, for example, is compelled to attend the chapel twice on every Sunday; if he evades it or shirks it he is punished. Is it to be wondered at, that when the time of real or of comparative liberty comes, they should cast off attendance at the house of God with every other mark of their bondage? I believe I may truly say that all the clergy, although they may be able to tell of many instances of reformed characters amongst the convicts, lament the difficulty they have experienced of bringing these men to Church”.

While Nixon did not visit the Coal Mines, his views on the inadequacies of religious instruction are echoed in letters written by James Purslowe, a former superintendent of the Bridgewater, Jerusalem and Impression Bay Probation Stations and who was in charge of the Coal Mines between 1843 and 1844. In 1846 he wrote a letter to Lord Stanley (then British Secretary of State for War and the Colonies) in which he expressed his concerns with the probation system. In one letter, he described a bizarre and un-Christian-like practices at a religious services at the Coal Mines:

“At the Coal Mines there were about 600 men. A paid minister attended on Sundays only. In the morning he performed service for the prisoners, and in the evening for the visiting magistrate and his lady. This was the system here. The magistrate and his lady objected to attend prayers with the prisoners, and the minister who received £200 per annum, devoted himself every sabbath afternoon to the magistrates' family - the gang being left in idleness. When the Archdeacon visited, he administered the Sacrament; several prisoners expressed their desire to receive it, and their names were given in, but only free people were allowed to partake thereof. The magistrate and his lady upon this occasion desired to attend the morning service, and having a repugnance against entering the chapel by the same door as the prisoners, applied to the foreman of works to take out a window; to this I objected; the magistrate and lady consequently declined to attend the service; but after its conclusion, when the chapel was cleared, received the sacrament from the hands of the Archdeacon….”.

The Catholic catechist attending the Coal Mines was based at Port Arthur. In an incident in July 1846, he was attacked by two convicts from the Salt Water Probation Station after returning from giving religious instruction to Catholics at the Coal Mine chapel.

Two convicts, Michael Roach and John Dangan were subsequently charged with assault and robbery of Mr Roger Boyle, who was bludgeoned leaving a wound on the left side of his head. The two convicts, who were described as “mere boys”, were promptly tried. Roach, “who did not appear to be more than 20 years of age”, was executed “at the usual place” in front of the Hobart gaol. Dangan was transported for life to Norfolk Island.

In delivering the sentence at the Supreme Court, the judge observed that:

“The offence was one for which death would be awarded by the law under any circumstances, but there was one very dark feature of this robbery and dreadful assault. At the Port Arthur Coal Mines, and the Salt Water Station, the prisoners were of the worst and most depraved of even their own class. They stood in especial need of spiritual instruction that they might, in some degree at least, reclaim their lost diameters, and avoid those desperate courses in future which had placed them in their unhappy position. Here was a gentleman devoting his life for their good - travelling from the Coal Mines to the other station, in order to instruct them in their duty to God and man….It was an awful thing to reflect upon. The blow must have been given with great violence, and with the worst intentions.… That Mr. Hoyle was not killed upon the spot, could only be ascribed to the intervention of the Almighty providence of God…”.

While Roach was no martyr, it is somewhat ironic that he met his death with apparent Christian dignity. Reverend Hall, the Vicar General, who ministered to Roach and prepared him for his death noted:

“He was an intelligent young man, and had been better educated than most of the unfortunate men of his class. He conducted himself with considerable firmness, and died penitent.”

The Coal Mines were officially closed as a probation station in 1848 on 'moral and financial grounds', although the mines continued to be worked privately until 1877. The Coal Mines are significant because of their role in the anti-transportation debate. The colonial administration and Tasmanian opponents to transportation considered the place as among the worst penal stations for “unnatural crimes”. This was a factor contributing to the demise of the probation system, and was also used as a means of swaying British public opinion against the further transportation of convicts to Van Diemen's Land.

|

| Buildings at Plunkett point on Tasman Peninsula, Tasmania. State Library of Victoria - Owen Stanley, Penal Settlement VDL, Convict prison near the Coal Mines, n.d. [January 1841] |

|

| Detail taken from a glass slide: Glass slide - Coal Mines Station / J W Beattie Tasmanian Series 496a - Libraries Tasmania - Item Number: NS4077/1/214 |

|

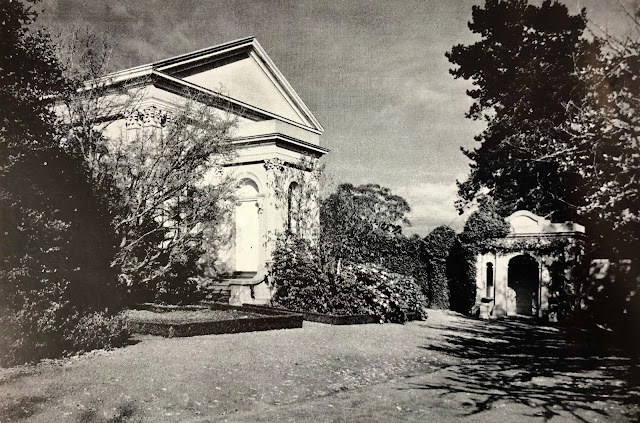

| The remains of the Chapel and schoolroom. TAHO: Item Number: NS3195/2/1583 |

|

| Plan for Prisoners Barracks: TAHO CON 87/83 |

Sources:

Launceston Examiner, Saturday 23 December 1843, page 4

Launceston Examiner, Wednesday 26 August 1846, page 6

Colonial Times, Friday 4 September 1846, page 3

Courier, Saturday 5 September 1846, page 2

Courier, Wednesday 30 September 1846, page 2

Launceston Advertiser, Thursday 1 October 1846, page 3

Launceston Examiner, Thursday 25 November 1846.

Courier, Wednesday 1 December 1847, page 2

James Purslowe, Letter to Lord Stanley, printed in the Launceston Examiner 25 November 1846.

Coal Mines Historic Site Visitor Guide, Port Arthur Historic Site Management Authority, 2013.

Andrew Piper, ‘The dregs of a criminal population: Impression Bay and the origins of Tasmania's residential charitable system, c. 1839-1857’, Journal of Australian Colonial History, Vol. 22, 2020, pp. 211-236.

Thompson, John,. Probation in paradise : the story of convict probationers on Tasman's and Forestier's peninsulas, Van Diemen's Land, 1841-1857 / by John Thompson J. Thompson [Hobart, Tas.] 2007

Tuffin, R.L.; Australia's Industrious Convicts: An Archeological Study of Landscapes of Convict Labour; A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Archaeology, University of Sydney

2016

The penal settlements of early Van Diemen's Land / by Thomas James Lempriere. http://handle.slv.vic.gov.au/10381/183068

State Library of New South Wales: TAS PAPERS 156: Port Arthur Convict Settlement : Permits, Conveyances and Expenditure, 1858-1860, and Other Convict Records, 1857-1864, Including Plans of Probation Stations, Tasman Peninsula, 1857.

Australia. Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts. Australian convict sites : world heritage nomination / Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts Dept. of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts Canberra 2008 <http://www.environment.gov.au/heritage/publications/about/pubs/convict-sites.pdf>

Port Arthur Historic Site Management Authority (Tas.), (author,) Coal Mines Historic Site master plan 2013. [Port Arthur Historic Site Management Authority?], [Port Arthur, Tasmania], 2013.

https://www.utas.edu.au/library/companion_to_tasmanian_history/C/Convicts.htm

Comments

Post a Comment