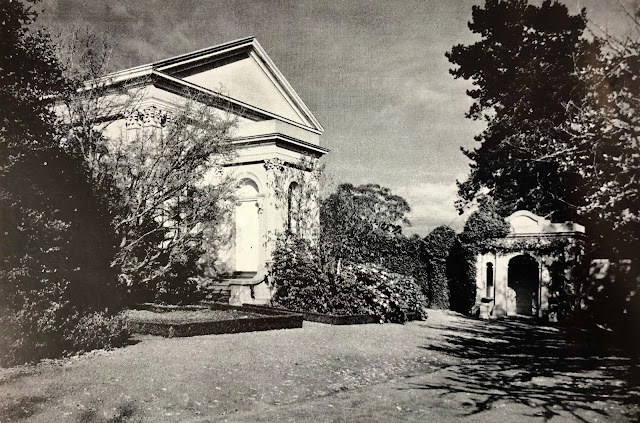

No. 1590 - Cape Barren Island - Church at The Corner (1893)

Cape Barren Island is the second largest island in the Furneaux Group. It is situated at the southern end of Flinders Island and separated by the Franklin Sound. The island is also known as truwana, an Aboriginal word meaning 'sleeping water’. In 1881 Cape Barren Island Reserve was established for the descendants of Aboriginal women and European sealers living in the Furneaux Islands of Bass Strait.

In 1871 the inhabitants of the Furneaux Islands petitioned Governor Charles Du Cane for a reserve and the exclusive use of the mutton bird rookeries. They received only two ten hectare blocks on Cape Barren Island for homesteads and agricultural activity. While the government accepted that the Islanders were a separate community it did not acknowledge that they had exclusive land rights based on their Aboriginality.

From the 1870s the Anglican Church sought to increase its influence on the Islands and, following a campaign by the Islanders, with the support of the Church, the government set aside a further 2500 hectares at Cape Barren. Initially ‘the reserve’ was jointly supported by the government and the Church. The role of the Anglican Church on the island is somewhat contentious and the complexities of this history is beyond the scope of this article. The history is however very interesting and a list of readings and sources are provided at the end of this article.

The development of the Cape Barren church is closely associated with Bishop Montgomery. In 1899 Montgomery (1847–1932) was appointed as the fourth Anglican Bishop of Tasmania. Characterised as a 'bush bishop', he enjoyed exploring the remote regions of Tasmania and he paid particular attention to descendants of the Tasmanian Indigenous community living on Cape Barren Island. He visited the Island on no less than 10 occasions and in 1893, after one such visit, Montgomery wrote:

“Having just visited the Furneaux Islands, will you permit me to tell the public something of the church lately built on Cape Barren Island… In the first place, too much praise can hardly be accorded to the school master for the manner in which, in addition to his other duties, he laid out the work and succeeded in keeping the people together till it was completed…..After weeks of work the church was built, and it stands, I venture to say, as an unique monument of the skill and patience of a….community under direction. Some of these people were in the habit of beginning work at four a.m. I have examined the structure carefully, and the neatness of execution is astonishing, bearing comparison with any church I know. I have sat in it when the awful winds which howl over these regions were trying to tear the roof from the walls, but the work has been done so well that it seems as if no gales could injure it. The entire expense of a beautiful church with a lofty roof and space enough for 200 people has been the price of the material, £110. Day after day the whole community worshipped in it, and its doors are never locked by day or night. Standing near the township, I hope it may be much used for private prayer at all times. I have never enjoyed services more than those in which I met this interesting community in a building which has such a history. Let us look back ten years, or even three years, and the advance made by these people in steadiness and moral growth is wonderful….”.

Following Montgomery’s departure from Tasmania the church went into decline but this was largely due to the fact that the settlement did not have a residential mission and the missionary/school teacher had little real moral authority. In 1908, a visit to Cape Barren Island by the American Consul, Henry S. Baker, reveals that the church, while maintained, was no longer in regular use:

“…I may add that I personally visited the church at Cape Barren Island, and was very much pleased with it….It seemed to me that a great deal of credit was due to the good people of Tasmania, who had advanced funds for this church to the [people] of Cape Barren Island, who had enthusiastically contributed their labour, and to Mr Storrer, M.H.R., who had very kindly given a beautiful carpet to the church. At the time of my visit the church was not open for services, but worship took place at the school house, Mr Knight, the schoolmaster, officiating. The church had recently been reconstituted, and it was a desire to have a re-dedication by some duly ordained minister, before holding services there. The people of Cape Barren Island were earnestly hoping that they would soon be favoured with a visit from such a minister, and I am glad to learn that since I left the group, the Rev. Fernau has been there, doing some good work. I was much impressed while in the islands with the popularity of the bishops and other churchmen who have visited the islands, where they have done so much good….”.

The decline of the church in the following years was mostly due to a decline in the Islands population. A 1929 report highlighted the impoverished living conditions of the Cape Barren Islanders. The report recommended that once children completed school they should be encouraged to leave the Island and the influence of their family. The government responded by appointing the head teacher on Cape Barren Island to the position of 'special constable'. This gave him the power to remove a child for neglect under the child welfare laws. Fearful of losing their children, many Indigenous families left the Island for mainland Tasmania.

By the 1930s the church ceased being used and fell into a state of disrepair. It was replaced by a new church in the 1940s. This building will be the subject of a second article.

In 1871 the inhabitants of the Furneaux Islands petitioned Governor Charles Du Cane for a reserve and the exclusive use of the mutton bird rookeries. They received only two ten hectare blocks on Cape Barren Island for homesteads and agricultural activity. While the government accepted that the Islanders were a separate community it did not acknowledge that they had exclusive land rights based on their Aboriginality.

From the 1870s the Anglican Church sought to increase its influence on the Islands and, following a campaign by the Islanders, with the support of the Church, the government set aside a further 2500 hectares at Cape Barren. Initially ‘the reserve’ was jointly supported by the government and the Church. The role of the Anglican Church on the island is somewhat contentious and the complexities of this history is beyond the scope of this article. The history is however very interesting and a list of readings and sources are provided at the end of this article.

The development of the Cape Barren church is closely associated with Bishop Montgomery. In 1899 Montgomery (1847–1932) was appointed as the fourth Anglican Bishop of Tasmania. Characterised as a 'bush bishop', he enjoyed exploring the remote regions of Tasmania and he paid particular attention to descendants of the Tasmanian Indigenous community living on Cape Barren Island. He visited the Island on no less than 10 occasions and in 1893, after one such visit, Montgomery wrote:

“Having just visited the Furneaux Islands, will you permit me to tell the public something of the church lately built on Cape Barren Island… In the first place, too much praise can hardly be accorded to the school master for the manner in which, in addition to his other duties, he laid out the work and succeeded in keeping the people together till it was completed…..After weeks of work the church was built, and it stands, I venture to say, as an unique monument of the skill and patience of a….community under direction. Some of these people were in the habit of beginning work at four a.m. I have examined the structure carefully, and the neatness of execution is astonishing, bearing comparison with any church I know. I have sat in it when the awful winds which howl over these regions were trying to tear the roof from the walls, but the work has been done so well that it seems as if no gales could injure it. The entire expense of a beautiful church with a lofty roof and space enough for 200 people has been the price of the material, £110. Day after day the whole community worshipped in it, and its doors are never locked by day or night. Standing near the township, I hope it may be much used for private prayer at all times. I have never enjoyed services more than those in which I met this interesting community in a building which has such a history. Let us look back ten years, or even three years, and the advance made by these people in steadiness and moral growth is wonderful….”.

Following Montgomery’s departure from Tasmania the church went into decline but this was largely due to the fact that the settlement did not have a residential mission and the missionary/school teacher had little real moral authority. In 1908, a visit to Cape Barren Island by the American Consul, Henry S. Baker, reveals that the church, while maintained, was no longer in regular use:

“…I may add that I personally visited the church at Cape Barren Island, and was very much pleased with it….It seemed to me that a great deal of credit was due to the good people of Tasmania, who had advanced funds for this church to the [people] of Cape Barren Island, who had enthusiastically contributed their labour, and to Mr Storrer, M.H.R., who had very kindly given a beautiful carpet to the church. At the time of my visit the church was not open for services, but worship took place at the school house, Mr Knight, the schoolmaster, officiating. The church had recently been reconstituted, and it was a desire to have a re-dedication by some duly ordained minister, before holding services there. The people of Cape Barren Island were earnestly hoping that they would soon be favoured with a visit from such a minister, and I am glad to learn that since I left the group, the Rev. Fernau has been there, doing some good work. I was much impressed while in the islands with the popularity of the bishops and other churchmen who have visited the islands, where they have done so much good….”.

The decline of the church in the following years was mostly due to a decline in the Islands population. A 1929 report highlighted the impoverished living conditions of the Cape Barren Islanders. The report recommended that once children completed school they should be encouraged to leave the Island and the influence of their family. The government responded by appointing the head teacher on Cape Barren Island to the position of 'special constable'. This gave him the power to remove a child for neglect under the child welfare laws. Fearful of losing their children, many Indigenous families left the Island for mainland Tasmania.

By the 1930s the church ceased being used and fell into a state of disrepair. It was replaced by a new church in the 1940s. This building will be the subject of a second article.

|

| Cape Barren Island Church c.1893 Photograph: Bishop H.H. Montgomery - Mitchell Library, State Library of New South Wales. A link to a digital copy of the original photograph can be viewed HERE |

|

| View of a funeral at the Cape Barren Island church. (undated photograph) Source: QVM:1992:P:1372 |

|

| View of Bishop Montgomery on the step of 'Bishopscourt', Cape Barren Island, Tasmania, c 1893. Source: QVM:1988:P:0482 |

Sources and Further Reading:

Launceston Examiner, Wednesday 1 February 1893, page 5

Launceston Examiner, Tuesday 21 February 1893, page 3

Mercury, Tuesday 21 February 1893, page 3

Launceston Examiner, Friday 17 March 1893, page 7

Daily Telegraph, Wednesday 12 April 1893, page 3

Launceston Examiner, Thursday 10 January 1895, page 7

Launceston Examiner, Thursday 10 January 1895, page 7

Tasmanian, Saturday 5 October 1895, page 46

Daily Telegraph, Thursday 9 July 1908, page 6

Mercury, Monday 16 August 1937, page 3

Boyce, James and Anglicare Tasmania. Social Action and Research Centre. God's own country? The Anglican church and Tasmanian Aborigines / James Boyce Social Action and Research Centre, Anglicare Tasmania Hobart, Tas. 2001

Stephens, Geoffrey & Anglican Church of Australia. Diocese of Tasmania, (issuing body.) The Anglican Church in Tasmania : a Diocesan history to mark the sesquicentenary, 1992. Trustees of the Diocese, Hobart, 1991.

Stephens, Geoffrey, ‘H.H. Montgomery – the Mutton Bird Bishop’, University of Tasmania, Occasional Paper 39, 1985.

Skira, Irynej Joseph. “'I Hope You Will Be My Friend': Tasmanian Aborigines in the Furneaux Group in the Nineteenth Century - Population and Land Tenure.” Aboriginal History 21 (2011): 30.

https://www.findandconnect.gov.au/entity/cape-barren-island-reserve/

https://samphiredeb.com/2013/07/13/bishop-montgomery-june-1894-visits-to-the-furneaux/

Comments

Post a Comment